eBook - ePub

The Reasoning Criminal

Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending

- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The assumption that rewards and punishments influence our choices between different courses of action underlies economic, sociological, psychological, and legal thinking about human action. Hence, the notion of a reasoning criminal-one who employs the same sorts of cognitive strategies when contemplating offending as they and the rest of us use when making other decisions-might seem a small contribution to crime control. This conclusion would be mistaken. This volume develops an alternative approach, termed the "rational choice perspective," to explain criminal behaviour. Instead of emphasizing the differences between criminals and non-criminals, it stresses some of the similarities. In particular, while the contributors do not deny the existence of irrational and pathological components in crimes, they suggest that the rational aspects of offending should be explored. An international group of researchers in criminology, psychology, and economics provide a comprehensive review of original research on the criminal offender as a reasoning decision maker. While recognizing the crucial influence of situational factors, the rational choice perspective provides a framework within which to incorporate and locate existing theories about crime. In doing so it also provides both a new agenda for research and sheds a fresh light on deterrent and prevention policies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Reasoning Criminal by Marvin Scott,Ronald V. Clarke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

DEREK CORNISH AND RONALD CLARKE

The chapters in this volume are the outcome of a conference sponsored by the Home Office at Christ's College, Cambridge, England, in July 1985. The conference was designed to provide a forum for exploring and elaborating a decision-making approach to the explanation of crime. This perspective, the organizers believed (Clarke and Cornish, 1985), was one increasingly being adopted by a number of social scientists in disciplines with an interest in criminal behavior. At the least, these various approaches—drawn from psychology, sociology, criminology, economics, and the law—seemed to assume that much offending was broadly rational in nature (Simon, 1978). Hence the "reasoning criminal" of this volume's title. In other respects, however, their concepts, aims, preoccupations, and terminologies were often quite different, and in consequence it was not always easy to appreciate how much common ground they shared. More tantalizingly, it was unclear to what extent the insights provided by the various disciplines could be integrated into a more comprehensive and satisfactory representation of criminal behavior. The organizers had already made one attempt to provide such a framework in the paper referred to above, and the conference provided a further opportunity to test out the possibilities for some such synthesis.

Rational Choice Approaches to Crime

The synthesis we had suggested—a rational choice perspective on criminal behavior—was intended to locate criminological findings within a framework particularly suitable for thinking about policy-relevant research. Its starting point was an assumption that offenders seek to benefit themselves by their criminal behavior; that this involves the making of decisions and of choices, however rudimentary on occasion these processes might be; and that these processes exhibit a measure of rationality, albeit constrained by limits of time and ability and the availability of relevant information. It was recognized that this conception of crime seemed to fit some forms of offending better than others. However, even in the case of offenses that seemed to be pathologically motivated or impulsively executed, it was felt that rational components were also often present and that the identification and description of these might have lessons for crime-control policy.

Second, a crime-specific focus was adopted, not only because different crimes may meet different needs, but also because the situational context of decision making and the information being handled will vary greatly among offenses. To ignore these differences might well be to reduce significantly one's ability to identify fruitful points for intervention (similar arguments have been applied to other forms of "deviant" behavior, such as gambling: cf. Cornish, 1978). A crime-specific focus is likely to involve rather finer distinctions than those commonly made in criminology. For example, it may not be sufficient to divide burglary simply into its residential and commercial forms. It may also be necessary to distinguish between burglaries committed in middle-class suburbs, in public housing, and in wealthy residential enclaves. Empirical studies suggest that the kinds of individuals involved in these different forms of residential burglary, their motivations, and their methods all vary considerably (cf. Clarke and Hope, 1984, for a review). Similar cases could be made for distinguishing between different forms of robbery, rape, shoplifting, and car theft, to take some obvious cases. (In lay thinking, of course, such distinctions are also often made, as between mugging and other forms of robbery, for example.) A corollary of this requirement is that the explanatory focus of the theory is on crimes, rather than on offenders. Such a focus, we believe, provides a counterweight to theoretical and policy preoccupations with the offender.

Third, it was argued that a decision-making approach to crime requires that a fundamental distinction be made between criminal involvement and criminal events. Criminal involvement refers to the processes through which individuals choose to become initially involved in particular forms of crime, to continue, and to desist. The decision processes in these different stages of involvement will be influenced in each case by a different set of factors and will need to be separately modeled. In the same way, the decision processes involved in the commission of a specific crime (i.e., the criminal event) will utilize their own special categories of information. Involvement decisions are characteristically multistage, extend over substantial periods of time, and will draw upon a large range of information, not all of which will be directly related to the crimes themselves. Event decisions, on the other hand, are frequently shorter processes, utilizing more circumscribed information largely relating to immediate circumstances and situations.

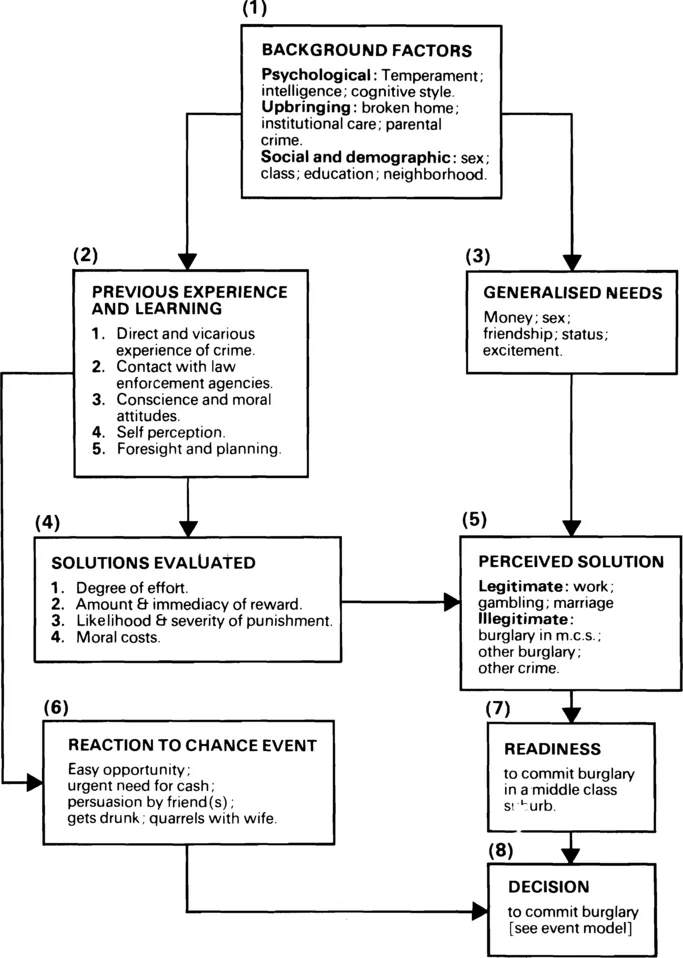

The above points can be illustrated by consideration of some flow diagrams that the editors previously developed (Clarke and Cornish, 1985) to model one specific form of crime, namely, burglary in a middleclass residential suburb. Figure 1.1, which represents the processes of

FIGURE 1.1. Initial involvement model (example: burglary in a middle-class suburb). (From Crime and Justice, vol. 6, M. Tonry and N. Morris (eds.), University of Chicago Press, 1985. By permission.)

initial involvement in this form of crime, has two decision points. The first (Box 7) is the individual's recognition of his or her "readiness" to commit the specific offense in order to satisfy certain needs for money, goods, or excitement. The preceding boxes indicate the wide range of factors that bring the individual to this condition. Box 1, in particular, encompasses the various historical (and contemporaneous) background factors with which traditional criminology has been preoccupied; these have been seen to determine the values, attitudes, and personality traits that dispose the individual to crime. In a rational choice context, however, these factors are reinterpreted as influencing the decisions and judgments that lead to involvement. The second decision (Box 8) actually to commit this form of burglary is the outcome of some chance event, such as an urgent need for cash, which demands action.

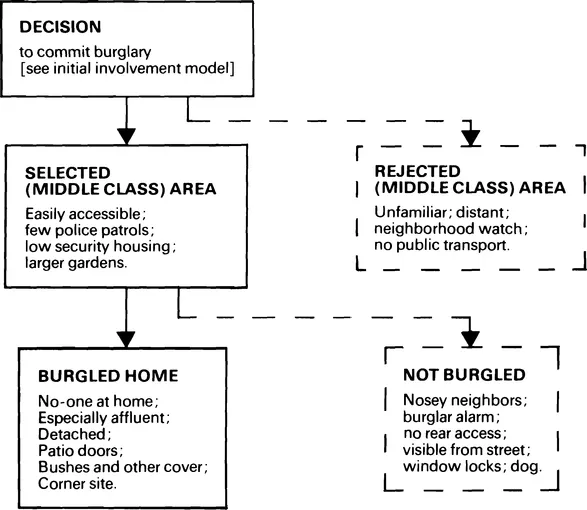

Figure 1.2, which is much simpler, depicts the further sequence of decision making that leads to the burglar selecting a particular house. The range of variables influencing this decision sequence is much narrower and reflects the influence of situational factors related to opportunity, effort, and proximal risks. In most cases this decision sequence takes place quite quickly. Figure 1.3 sketches the classes of

FIGURE 1.2. Event model (example: burglary in a middle-class suburb). (From Crime and Justice, vol. 6, M. Tonry and N. Morris (eds.), University of Chicago Press, 1985. By permission.)

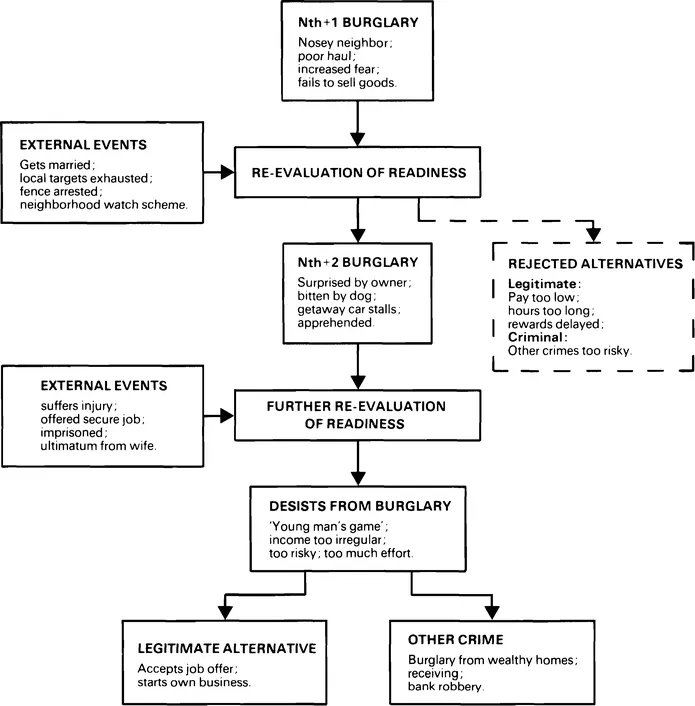

FIGURE 1.3. Continuing involvement model (example: burglary in a middle class suburb). (From Crime and Justice, vol. 6, M. Tonry and N. Morris (eds.), University of Chicago Press, 1985. By permission.)

variables, relating to changes in the individual's degree of professionalism, peer group, life-style, and values, that influence the constantly reevaluated decision to continue with this form of burglary.

Figure 1.4 illustrates, with hypothetical data, similar reevaluations that may lead to desistance. In this case, two classes of variables are seen to have a cumulative effect: life-events (such as marriage), and those more directly related to the criminal events themselves.

These, then, are the main features of the framework that was developed out of our review of recent work in a variety of disciplines that have an interest in crime. It differs from most existing formal theories of criminal behavior, however, in a number of respects. It is true that, like many other criminological theories, the rational choice perspective is intended to provide a framework for understanding all forms of crime. Unlike other approaches, however, which attempt to impose a conceptual unity upon divergent criminal behaviors (by subsuming them under more general concepts such as delinquency, deviance, rule breaking, short-run hedonism, criminality, etc.), our rational choice formulation sees these differences as crucial to the tasks of explanation and control. Unlike existing theories, which tend to concentrate on factors disposing individuals to criminal behavior (the initial involvement model), the rational choice approach, in addition, emphasizes subsequent decisions in the offender's career. Again, whereas most existing theories tend to accord little influence to situational variables, the rational choice approach explicitly recognizes their importance in relation to the criminal event and, furthermore, incorporates similar influences on decisions relating to involvement in crime. In consequence, this perspective also recognizes, as do economic and behaviorist theories, the importance of incentives— that is, of rewards and punishments—and hence the role of learning in the criminal career. Finally, the leitmotif encapsulated in the notion of a "reasoning" offender implies the essentially nonpathological and commonplace nature of much criminal activity.

Empirical Studies of Criminal Decision Making

Part 1 of this volume consists of a number of empirical studies of shoplifting (Carroll and Weaver), robbery (Cusson and Pinsonneault, Feeney, Walsh), commercial burglary (Walsh), and opioid use (Bennett). Considered merely as additions to the crime-specific literature, these studies contribute greatly to our knowledge about particular offenses. This may be illustrated by a few of the more unexpected findings: that many robberies are impulsive and unplanned (Feeney, Walsh), that some robbers avoid burglary for fear of encountering the householder (Feeney), and that, prior to their first experience of drug use, many opioid users had already apparently decided that they wanted to become part of the "drug scene" (Bennett). Additionally, although not necessarily designed with the above formulation of the rational choice approach in mind, these studies also exemplify the kind of detailed empirical work needed to test, refine, and elaborate our models.

FIGURE 1.4. Desistance model (example: burglary in a middle class suburb). (From Crime and Justice, vol. 6, M. Tonry and N. Morris (eds.), University of Chicago Press, 1985. By permission.)

In our discussion of the rational choice perspective we identified three main components: the image of a reasoning offender, a crime-specific focus, and the development of separate decision models for the involvement processes and the criminal event The empirical studies both give some support to the above analysis and permit further refinements. In regard to the nature of offender decision making, the present studies suggest that, although offenders act in a broadly rational fashion, normative economic models such as the expected utility (EU) paradigm fail to capture the cognitive activities involved. (This point is referred to again below.) Furthermore, there is evidence from Carroll and Weaver's study that information-processing strategies change with growing expertise. As far as the second element is concerned, the importance of a crime specific approach has already been noted above in relation to the insights provided about particular crimes. The necessity of such a focus is reinforced by Walsh's comparisons between commercial burglars and robbers: Although similar proportions in each group claimed to plan their offenses, there was some evidence of differences in the form and content of the reasoning involved. Within categories of crime, too, it seems that further differentiation may have some value: Feeney, for example, found that commercial robberies were more often planned than those committed against individuals. Blazicek's recent (1985) study of target selection by commercial robbers tends to support this finding, and his results also indicate that a further breakdown of commercial robbery into more specific categories might be useful. More generally, information from his respondents suggests that, when selecting their commercial targets, such robbers apparently attach more importance to the overall scenario—numbers of people inside the establishment, its size and location—than to the personal characteristics of the human victims involved. Since studies like Lejeune's (1977) on mugging have shown victim characteristics to play a more central role in relation to target selection, it would be interesting to know more about the relative importance of scene and victim characteristics for other offenses.

The empirical studies support in general terms the separate modeling of event and involvement processes. (This issue, too, relates to the nature of criminal decision-making processes and will be discussed in more detail later.) However, they also suggest the need for some qualifications: For example, Cusson and Pinsonneault's analysis, with its emphasis on the possibility of "backsliding," suggests that desistance from a particular type of crime may not always be the smooth process of disengagement that our model might suggest. Their concepts of "shock" and of "delayed deterrence" leading to desistance further stress the discontinuities involved. (In passing it should be noted that the concept of desistance, and indeed of involvement, assumes repeated offenses. Although this assumption undoubtedly holds for many crimes, there is a limited class, including domestic murder, for which it will not.)

Lastly, the authors of these chapters (in particular, Carroll and Weaver, Walsh) raise some of the methodological problems commonly encountered when carrying out such empirical research. Many of these considerations will be especially relevant to studies of event decisions, but others will be found to apply equally to questions of involvement, continuance, and desistance. The problems can be divided into two broad categories: those of contacting and enlisting the cooperation of "real" criminals, and those of providing a research context and, where relevant, a decision task likely to elicit valid information about criminal decision making. Unfortunately, these two groups of requirements often tend to conflict. To guarantee the representativeness of one's sample, it might seem sensible to contact those convicted of such offenses, large clusters of whom are, in any case, conveniently located in prisons. Although these populations do not (as is often claimed) necessarily contain an overrepresentation of unsuccessful offenders—the criminal records of convicted burglars and robbers are likely to be only the tips of their personal offending icebergs—the data may well contain other systematic distortions: for example, the presence of large numbers of older, more serious, and more persistent offenders may exaggerate the role of experience and planning in decision making.

Although problems in gaming the cooperation of incarcerated offenders may be encountered (Walsh), the difficulties are considerably magnified where the decision is made to use those currently at liberty. The confidentiality of agency files, the covert nature of criminal activity, and the difficulty of penetrating criminal networks all make the task of identifying and contacting criminals (cf. Klockars, 1974; Carroll and Weaver) and ex-criminals (Cusson and Pinsonneault) a hard one; even when respondents are found, the problems remain of verifying their credentials and estimating their representativeness.

Such problems interact with those of trying to ensure that information about criminal decision making is elicited in ways that guarantee authenticity and verisimilitude. Bennett has elsewhere (Bennett and Wright, 1984) graphically cataloged the practical difficulties of undertaking process-tracing research with burglars. Moreover, the well documented ethical and legal problems of carrying out participant observation studies with criminals (cf. Weppner, 1977)—to say nothing of the personal dangers sometimes involved—will usually place similar constraints on process tracing, limiting the method at best to the study of induced behavioral intentions rather than the commission of criminal acts. This will mean that, although questions of procedural rationality can be addressed by such studies, the effectiveness of the identified decision processes in achieving their outcomes cannot be directly explored. Even this research might be viewed as ethically dubious where serious personal crimes are being studied, especially those regarded as having pathological components, if those using the procedure were to be suspected of condoning, colluding in, or encouraging the consideration of such offenses.

However, in vitro techniques, such as process tracing using video recordings (cf. Bennett and Wright, 1984) or retrospective interviewing using still photographs to stimulate discussion and simulate important aspects of the decision problem, may fail to capture essential elements of the real-life task or decision-making processes, even if the method enables the salient information being used to be correctly identified. At worst there is the danger that a largely fictional gloss of rationality, born out of the demands of the researcher and the needs of the offender, could be imposed post hoc on previous offending o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- Preface

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Part One Empirical Studies of Criminal Decision Making

- Part Two Theoretical Issues

- Author Index

- Subject Index