![]()

Part I: Monetizing Information as an Asset

![]()

Chapter 1

Why Monetize Information

Take the A1081 heading towards Harpenden and St. Albans. After about two miles you will come to a mini roundabout, carry straight on towards Harpenden. Take the first turn on the left after a quarter-mile, signed “Thrales End Lane.” After another quarter-mile the road takes a sharp right hand-bend, just before this corner there is an entrance on your left hand side signposted “Thrales End Business Centre.”1

You are now at the farm of Ian Pigott somewhere in Hertfordshire, England. This wheat, oats, and barley farm may be at the “end of Thrales,” but it’s at the forefront of monetizing information.

Pigott watches as his autonomous 11-ton John Deere tractor thunders across two thousand acres of farmland every week or so. It is guided by information coursing back and forth from a satellite—directed by information from weather forecasts, soil readings, pesticide use, and plant samples—and streaming nutrition and other information to the farmer’s tablet. From a comfy chair in his office, Pigott can monitor and manage the entire operation, in real time, down to the square meter. Other similarly tricked-out farms use drones to survey for crop stress or flooding, sense and locate underground aquifers, precisely portion out animal feed, and use infrared cameras to identify flock fevers indicative of bird flu.2

Due to information-fueled analytics and information, farming has become just another white-collar desk job. Sure, kicking back, putting up your feet, and running a farm may be cool—but let’s “follow the money,” as they say.

Despite the 800 percent increase in the cost of these sensor-loaded, intelligent combines and other ag-gadgetry, farms also like Tom Farms in Indiana benefit from a 50 percent increase in profits. The ability to farm twenty thousand acres today versus seven hundred acres in the 1970s with the same number of employees no doubt is a major contributing factor. How about eliminating the need for crop diversification to hedge against weather, disease, and market conditions? Information about markets, soil, and weather, combined with precision information-driven efficiencies enable the farmer to grow whatever will be most profitable.3

Moving up the economic food chain, do you think the farm equipment manufacturers like Deere and Caterpillar simply are profiting from their computerized crop creators? Hardly. They’re capturing data from them to help maintain and service them, get smarter about conditions and operations, design the next generation of equipment, sell more of it, and license to seed and fertilizer companies like Monsanto and Archer Daniels Midland. In turn, these companies use the information to develop new agricultural products, and even to identify farms illegally using them. And ultimately grocery stores, restaurants, and consumers benefit from higher quality products and lower prices.

Looking across several levels of this agricultural supply chain, we can identify a parallel information supply chain in which information is used to:

- Improve operational efficiencies,

- Improve maintenance,

- Improve production,

- Improve quality,

- Improve sales,

- Improve product development, and

- Improve business relationships.

Each of these capacities represents a discernible, discrete economic benefit in which information can be monetized, managed, and measured. And when any of these go unattended, you’re leaving money on the table. This is what infonomics aims to solve.

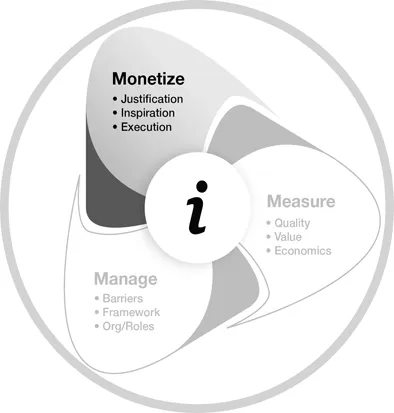

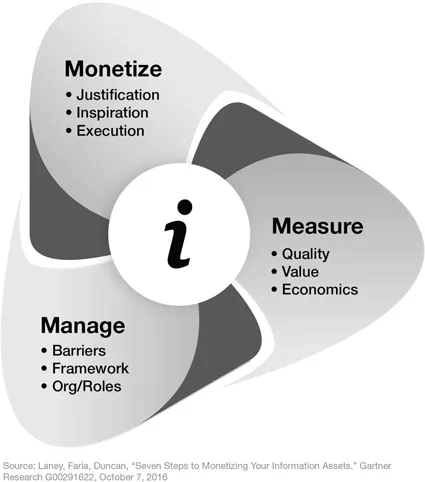

Monetize, Manage, and Measure Your Information

Infonomics is the theory, study, and discipline of asserting economic significance to information. It provides the framework for businesses to monetize, manage, and measure information as an actual asset. Infonomics endeavors to apply both economic and asset management principles and practices to the valuation, handling, and deployment of information assets.

As a business, information, or information technology (IT) leader, chances are you regularly talk about information4 as one of your most valuable assets. Do you value or manage our organization’s information like an actual asset? Consider your company’s well-honed supply chain and asset management practices for physical assets, or your financial management and reporting discipline. Do you have similar accounting and asset management practices in place for your “information assets?” Most organizations do not.

When considering how to put information to work for your organization, it’s essential to go beyond thinking and talking about information as an asset, to actually valuing and treating it as one. The discipline of infonomics provides organizations a foundation and methods for quantifying information asset value and formal information asset management practices. Infonomics posits that information should be considered a new asset class in that it has measurable economic value and other properties that qualify it to be accounted for and administered as any other recognized type of asset—and that there are significant strategic, operational, and financial reasons for doing so.

Infonomics provides the framework businesses and governments need to value information, manage it, and wield it as a real asset. Aptly, the topic coincides with the objectives and responsibilities of one of the hottest roles in businesses today: the chief data officer, or CDO. Most of the thousands of CDOs appointed in the past few years have been chartered with improving the efficiency and value-generating capacity of their organization’s information ecosystem. That is, they’ve been asked to lead their organization in treating and leveraging information with the same discipline as its other, more traditional assets. This book is for them.

This book also is for CEOs who want to guide their organizations from just using information to weaponizing it. It is for CIOs who want to transform their organizations from regarding information as “that stuff IT manages” into a critical business asset. It’s also for the CFO who is heads-up to the economic benefits of information, but is looking for ways to better understand, gauge, and financially leverage these benefits. And this book is also for the enterprise architect who wants a new set of tools to create novel information-based solutions for the organization, and for academics in business and computing sciences forming and shepherding the next generation of leaders into the Information Age.

This book is structured in three parts to provide a comprehensive guide for how to monetize, manage, and measure your information (Figure 1.1). First, we’ll examine why information affords unique opportunities to monetize it both directly and indirectly and give you a range of examples to help justify the business case for monetizing your organization’s information. This first section on monetizing information as an asset provides the justification, inspiration, and execution methods and closes out with an examination of advanced analytics and how to exploit Big Data for monetizable insights.

In part II, we’ll tackle the challenges and best practices for managing your internal and external information as an asset and how to structure your organization and roles to build an infosavvy organization. This section on managing information as an asset addresses the barriers to doing so, provides new ways to approach information asset management, and suggests a set of “Generally Accepted Information Principles” for doing so. Part III breaks down the current limitations to measuring information as an asset while offering new tools to measure the various benefits and costs of information. It also provides specific information valuation models and adapts key economic principles to help you begin quantifying and maximizing the benefits of your information assets.

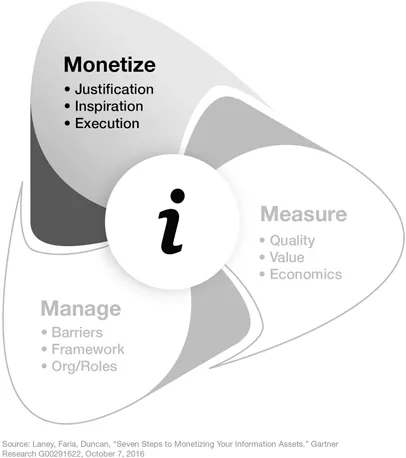

Figure 1.2 Infonomics—Monetize Information

The Possibilities of Information Monetization

Let’s dispel the notion right away that information monetization (Figure 1.2) is just about selling your data. It’s much broader than that. In today’s information economy we see a range of possibilities: information is used as legal tender (or at least in place of legal tender in many kinds of transactions); information most certainly is used to generate a profit—and not just by Google, Facebook, and the rest of the digerati, but by just about every business in every industry today with even just a copy of Excel—and information is regularly converted into money by a growing marketplace of household-name data brokers such as ACNielsen, Bloomberg, and Equifax, and by upstarts like Tru Optik, AULIVE, and hundreds (perhaps thousands) of others.

The imperative to monetize information in traditional businesses in all industries has become palpable. A 2015 Gartner study found that among the top ten Big Data challenges, respondents cited “how to get value from Big Data” as the number one challenge three times more often than any other challenge. Value challenges are cited five times more often than staffing related, leadership, or infrastructure/architecture challenges, and three times more often than risk or governance issues. By 2016, the same survey revealed a shift from how to get value to “determining value” as the biggest challenge—an indication of the need to measure the outcomes (which we’ll deal with in chapter 12).

The range of ways for any organization to monetize information is nearly endless. In chapter 2 we’ll examine several inspirational real-world stories of information being monetized across industries and business functions. The remainder of this chapter challenges the common myths that prevent information monetization within an organization, and presents opportunities to leverage information’s unique characteristics for real economic benefit.

Top Information Monetization Myths

Even with many well-publicized stories, several information monetization myths create cognitive roadblocks that hinder business leaders from realizing anything near the full promise of information:

- Information must be sold to be monetized,

- Monetization requires an exchange of cash,

- Monetization only involves your own information,

- Monetized information typically is in raw form,

- One must be in the information business to monetize information,

- Few others would want our information, and

- It’s best for us just to share our information with our suppliers and partners.

As a way to cleave through the cerebral fog of these myths, let’s first explore some key reasons why monetizing information is not only an excellent idea, but an increasing imperative for businesses.

Endless Economic Alternatives for Information

The first mental roadblock to monetizing information is a failure to think beyond selling it. It’s best not to get painted into that corner, lest you limit the economic potential of your information assets. Instead, think more broadly about “methods utilized to generate profit.” These methods can range from indirect methods in which information contributes to some economic gain, to more direct methods with which information may generate an actual revenue stream.

Indirect methods of information monetization can include using data to reduce costs, improve productivity, reduce risks, develop new products or markets, and build and solidify relationships.

Indirect methods for monetizing information abound, and we do them daily and for most processes. The problem is that most organizations don’t measure the information’s economic impact. So how can they claim they’re monetizing it? They can’t, really. In part III, I’ll describe how to measure the economic impact of information. An inability to measure information’s top or bottom line impact shouldn’t stop you from using it, but in reality it probably does limit how well, how broadly, and how creatively you deploy it. So let’s put a stake in the ground: You are indirectly monetizing information only if you are measuring its economic benefits. This may not quite be an aphorism, but it’s certainly useful.

Consider March 5, 2015, when Citigroup added $9 billion in market capitalization and a dividend increase of 500 percent. That morning the U.S. Federal Reserve had released the results of the second phase of its annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) stress tests on major banks.5 Citigroup had passed with flying colors—the cleanest test of top U.S. banks—by correlating and analyzing 2,600 macroeconomic variables with revenue streams from dozens of business units with the help of machine intelligence technology from Ayasdi.6 They had uncovered variable permutations which were difficult to identify using basic business intelligence approaches, and reduced this process from three months to t...