![]()

1

Drug Discovery Trends

There’ll always be serendipity involved in discovery.

Jeff Bezos

1.1 Introduction

If the number of drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can be taken as a measure of success, then there is a steady approval pace; over the past 4 years, 2015–2018, the FDA has already approved approximately 150 novel drugs and about 500 since the year 2000, bringing the total novel drugs approved to about 1500 since the year 1930. The new drugs under development are into thousands; for example, at least 500 new drugs are currently developed for neurological disorders that affect 100 million Americans.

Much has changed in the discovery of drugs over the past 50 years; the pace of change has accelerated exponentially since the first edition of this book was published. Microprocessor-driven instrumentation has revolutionized data-handling systems, robotic systems have eased large sample processing, and the integration of various physical and chemical sciences has resulted in the emergence of newer techniques. For example, high-throughput screening (HTS) is now an integral component of the drug discovery process that has evolved over the past decade from crude automation to the use of sophisticated computer-driven array systems using robotic devices. Improved physicochemical data on prospective new active entities (NAEs) provide a great stimulus to new drug development, as well as offer insights for the preformulation scientists to project the characteristics of the NAEs that would prove useful in their downstream processing. The downstream processes include hit-to-lead (HTL); lead optimization (LO); and in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and toxicology (ADMET) studies, all driven by the peculiar characteristics of the NAE.

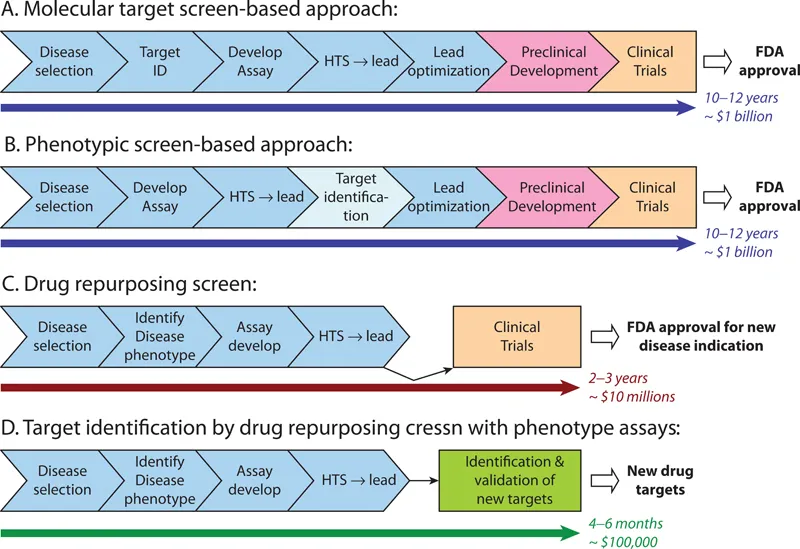

Figure 1.1 shows the most common types of drug discovery modalities, their costs, and the time it takes for the discovery.

1.1.1 Genome Editing

Targeted genome editing technology, based on the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system, offers a great promise for the future of medicine. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats or CRISPR refers to the system consisting of two key molecules: an enzyme Cas9—“molecular scissors,” able to cut the two strands of DNA at a specific location in the genome, and a piece of predesigned RNA sequence—“guiding” RNA (gRNA), within a longer RNA scaffold. The role of the latter is to direct Cas9 “scissors” to the exact location in the DNA of interest and modify it as desired. The CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing approach has transformed the biomedical research field forever. Compared with its “predecessors,” such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), the CRISPR-Cas9 system is simpler, more precise, and relatively cheaper, making it an ideal vehicle for “playing with genome.” On October 10, 2018, the FDA announced that it has lifted the clinical hold and accepted the Investigational New Drug (IND) application for CTX001 for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD), the first CRISPR product.

FIGURE 1.1 Comparison of phenotype screen and drug development using drug repurposing screen, with traditional process of drug discovery. (From https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4531371/.)

With a number of existing strategies to influence the immune systems, such as using checkpoint inhibitors, vaccines, and monoclonal antibodies, it is the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy where a patient’s own immune cells (or cells from another donor) are removed and modified, so that they can recognize and attack the patient’s particular cancer. The engineered CAR T-cells are then grown in the lab to reach billions in numbers, followed by infusion back into the patient’s body. The CAR T-cell technology has already proved to be extremely promising in the case of hard-to-treat lymphoma and is considered an ultimate future of the immunotherapy field. The FDA has approved two CART products.

1.1.2 Microbiome

The microbiome trend is growing rapidly and can possibly become one of the major game-changers in the biopharmaceutical industry. Microbiota is the ecosystem of more than 100 trillion microorganisms living inside our body or on the skin, coexisting naturally with human organism and performing vital functions such as the synthesis of vitamins, digestion, and taking part in the development of the immune system. The versatility of genes of the microbiota—microbiome—attracts the increasing interest of research community and biotech companies, as they try to develop new therapies or even find novel antibiotics by using the understanding of how our own bacteria contribute to diseases, immune responses, and the overall condition of an organism.

1.1.3 Antibiotics

The efforts for the discovery of new antibiotics have changed significantly after a long silent period. Over the last several years, the main drivers for the revived interest are the new stimuli created by the government and private organizations. Examples in the United States include the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act of 2012 and a more recent qualified infectious disease product (QIDP) designation for antibiotics and antifungals, which provides new candidates with priority review and five additional years of market exclusivity when approved. Further support could come from the 21st Century Cures Act, approved by the House in July 2015, which includes the Antibiotic Development to Advance Patient Treatment (ADAPT) Act that permits the FDA to approve antibacterial drugs to treat serious or life-threatening infections, based on small clinical trials.

The increasing need for new antibiotics and new incentives available for business stimulate new biotech startups to emerge. Some of the recent examples include Forge Therapeutics (small molecule inhibitors of LpxC, a zinc metalloenzyme in gram-negative bacteria), Cidara Therapeutics (immunotherapy platform to fight bacterial infections), Visterra (antibody–drug conjugate therapy), Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals, Macrolide Pharmaceuticals, Iterum Therapeutics, Spero Therapeutics, and Entasis Therapeutics.

1.1.4 Artificial Intelligence

Besides the mechanical approaches to drug discovery, the functional classification of what constitutes a drug has also changed exponentially, from gene-driven therapies to artificial intelligence (AI)-based treatment modalities. We have now entered an era that was impossible to visualize even a decade ago.

The AI and machine learning advances have already been in practical use for some time in many industries, including smart cars, natural language processing (NLP), image recognition, smart online search and recommendations, fraud detection, financial trading, weather forecasting, personal and data security, and chatbots, to name a few. However, the biopharmaceutical industry is just beginning to adopt the new computational technologies, though quite rapidly.

1.1.5 Marijuana

The legalization of marijuana in the United States and the use of marijuana for recreational use in Canada have sparked a growing interest of investors, who now turn their focus to the small—but rapidly expanding—medical marijuana industry. It is estimated that the global market for medical marijuana could reach $50 billion by 2025.

While United States is now the biggest market for medical-grade cannabis, Israel is pushing hard to position itself as a global player in this rapidly growing area of biopharmaceutical research. It is reported that about 120 research programs, including clinical trials looking at the effects of cannabis on autism, epilepsy, psoriasis, and tinnitus, are active in Israel.

The FDA has not approved marijuana as a safe and effective drug for any indication. The agency has, however, approved one specific drug product that contains the purified substance cannabidiol, one of more than 80 active chemicals in marijuana, for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients 2 years of age and older. The FDA has also approved two drugs containing a synthetic version of a substance that is present in the marijuana plant and one other drug containing a synthetic substance that acts similarly to compounds from marijuana but is not present in marijuana. The FDA is aware that there is considerable interest in the use of marijuana to attempt to treat a number of medical conditions, including, for example, glaucoma, AIDS wasting syndrome, neuropathic pain, cancer, multiple sclerosis, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and certain seizure disorders.

1.1.6 Target-Based Discovery

A vital part of any small-molecule drug discovery program is hit exploration—the identification of those starting point molecules that would embark on a journey toward successful medications (however, they rarely survive this journey)—via numerous optimization, validation, and testing stages. The key element of hit exploration is the access to an expanded and chemically diverse space of drug such as molecules to choose candidates from, especially for probing novel target biology. Given that the existing compound collections at the hands of pharma were built in part based on the small-molecule designs targeting known biological targets, new biological targets require new designs and new ideas instead of recycling.

Target-based drug discovery has enabled a great expansion of chemotypes and pharmacophores available for the medicinal chemist during the past three decades. New techniques such as HTS, fragment-based screening (FBS), crystallography in combination with molecular modeling, and combinatorial and parallel chemistry have created a considerable diversity of chemical lead structures well beyond the known natural products and ligands used as chemical starting points for drug discovery in the past. Moreover, this wealth of chemotypes can now be used as a source for tool compounds to study unexplored biological space and find new drug targets or for phenotypic screening by using systems-based approaches to identify drug candidates in a target-agnostic manner.

1.1.7 High-Through Screening

Typically, the libraries are composed of the compounds synthesized over time by individual companies and influenced by a company’s history; for example, Novartis has a large number of ergot compounds in its library, and Roche would have many benzodiazepines. However, as many companies work on similar targets or scaffolds, there must also be some overlap between the libraries. These libraries are a key component of the success of pharmaceutical companies; however, they have once been in danger of getting lost. At the time when combinatorial chemistry became possible in the 1980s, ...