eBook - ePub

Complexity in Urban Crisis Management

Amsterdam's Response to the Bijlmer Air Disaster

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Complexity in Urban Crisis Management

Amsterdam's Response to the Bijlmer Air Disaster

About this book

First published in 1994. A major air crash destroying a large number of flats in a densely populated suburb shocked the city of Amsterdam and highlighted the dangers of airports in the vicinity of urban centres. This book provides a minute-by-minute account, analysis and evaluation of how local authorities responded to the disaster that took place in the Bijlmer area of Amsterdam in October 1992.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Complexity in Urban Crisis Management by U. Rosenthal,et al in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Bijlmer disaster – the events

Sunday evening, 4 October 1992: the crash and the initial response

Flight LY 1862

Just before 18.30 on the evening of Sunday 4 October 1992 an El Al Boeing 747 took off from Schiphol, the main airport in the Netherlands (located near Amsterdam). The four people on board the Israeli freight plane, three crew members and a passenger, were on their way to Tel Aviv.

The first few minutes of the flight were uneventful, but shortly after take-off the crew were confronted with technical problems. In his first alarm message to the Schiphol control tower, the captain reported that both starboard engines had stopped functioning. At this time the crew were probably unaware that starboard engines 3 and 4 had become detached from the wing and had fallen into a lake.1 Seemingly calm, Captain Fuchs requested permission to return to Schiphol airport. Only minutes after the plane’s departure, the captain suddenly announced that he was experiencing problems in controlling the aircraft. The last message from the flight deck followed seconds later: ‘LY 1862, going down, going down’.2 At 18.36 the Boeing 747 freighter disappeared from the radar screen.

The 747 crashed into a neighbourhood known as ‘the Bijlmer’, situated in Southeast Amsterdam. The aircraft plunged directly into two, linked blocks of 10-storey flats, named ‘Groeneveen’ and ‘Kruitberg’, precisely at the corner where one joined the other. The damage caused by the plane’s impact was enormous. Thirty-one flats were demolished at a single blow, causing a gaping hole where before the apartment buildings had connected. Almost instantaneously, flames engulfed the apartments neighbouring the ones hit by the plane. Fed by the fuel from the aircraft’s tanks, the inferno consumed another 49 flats. The apocalyptic impression of the disaster site was reinforced by the ground fires blazing everywhere in the wreckage of the aircraft and the buildings. Whipped by a strong wind, thick columns of smoke rose up, masking the crash area. The combination of impact, smoke and fire damage made a total of 266 apartments uninhabitable.3 Later, part of the complex would have to be demolished.

Immediately after the crash, there was total chaos in and around the two buildings now separated by a burning pile of rubble. People living in adjacent units managed to escape from the blazing buildings, while others entered the buildings in an attempt to reach and rescue possible casualties. Of the final death toll of 43, most had lived in the 31 flats hit directly by the aircraft. The dead also included the El Al crew and their passenger.

Raising the alarm

The operational services. For the operational services involved, it was clear from the start that this was a major incident. Despite initially contradictory reports on the location of the crash, within a few minutes the police established from incoming calls that the aircraft had come down on these two blocks of flats in the Bijlmer. Personnel and equipment from various disaster teams were mobilised immediately and directed to the disaster site: the first ambulance was on its way at 18.37. Taxi drivers volunteered to take casualties to nearby hospitals, at no charge. The central reception point for medical assistance was the Academic Medical Centre (AMC) – the university hospital – where the disaster plan was put into operation at 19.14. Hospitals in nearby communities were on stand-by.

Firemen at the local fire station had witnessed the aircraft crashing into the apartment blocks and arrived very shortly after with the two available fire trucks. Other fire departments, including Schiphol Airport’s specially equipped crash tenders, also made for the site of the disaster. Within 90 minutes of the crash almost 300 fire-fighters were in action at the wrecked buildings.

Ten minutes after impact, dozens of police officers were on their way to the scene. Both on the spot and in the vicinity, the police soon had their hands full keeping out sightseers and sealing off the disaster area. During the course of Sunday evening, some 500 officers were deployed, including motorcycle, mounted and riot squad units.

The authorities. The Mayor of Amsterdam, Ed van Thijn, was at home watching his favourite soccer team Ajax play on TV when he received a call from the head of the city’s Information Department. She told him she had heard that an aircraft had crashed in the Bijlmer. The Mayor’s first reaction was disbelief.4 When the Chief of Police, Nordholt, confirmed the report some minutes later, Van Thijn realised that a catastrophe had just occurred in his city. At around 19.15, the Mayor issued a verbal statement declaring the situation a disaster.

Following the guidelines of the Amsterdam disaster plan, the Co-ordination Centre went operational. Located in a bomb-proof shelter under City Hall, the Co-ordination Centre was specially constructed for times of major emergency; it is equipped with modern communications equipment and can accommodate a large group of people for lengthy periods. It was here that the Mayor and his officials assembled. Most of those who had been alerted arrived at City Hall before 20.00.5

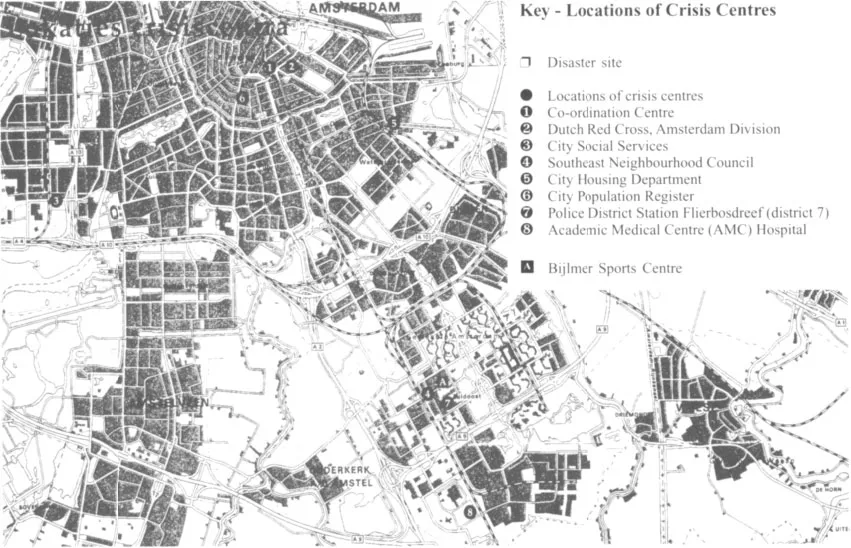

During the first hour efforts were devoted to establishing direct lines of communication with the disaster site. While the Co-ordination Centre filled up with people, the Head of Public Order and Safety acted as Co-ordinator for the Centre. In this position she introduced newcomers to the Co-ordination Centre and allocated their tasks. Once they had found their places, these officials tried to make contact with their own services. During the first few hours after the crash, activity in the Co-ordination Centre focused on getting a picture of the scale of the disaster, while at the same time work got underway on organising counter-disaster measures (see the map on p. 12 for an overview of locations of crisis centres).

Emergency services

At the disaster site, fire-fighters were busy dousing proliferating ground fires and containing the spread of flames in the stricken buildings. The raging inferno hampered the attempts of rescue workers to reach ‘Groeneveen’ and ‘Kruitberg’. Despite this, fire-fighters managed to search several sections of the two buildings. No survivors were found. Meanwhile there was a constant risk of the buildings collapsing and the added danger of explosion from gas mains and aircraft parts, so the gas mains were sealed off during the course of the evening. Following the crash, a growing stream of people moved towards the disaster area, creating heavy pressure on the temporary police lines around the site. Initially, these ‘disaster tourists’ could simply walk through at certain points but, two hours after the disaster occurred, the police started to clear people away from the area. Major traffic jams clogged roads in the immediate vicinity as routes leading to the disaster site were largely blocked by the inflow of spectators and people trying to find out whether their friends or relatives had been hurt.

Despite the traffic chaos, fire-fighting progressed well. Just over an hour after impact, the wreckage of the aircraft and the buildings were covered by a blanket of foam, and the danger of explosion dissipated. At 21.07, two and a half hours after the aircraft had crashed, the fire service announced that the fire was under control, although it would be 22.30 before the most important seats of the fire had been extinguished. Under the floodlight of hovering helicopters, a fire brigade rescue squad prepared to go into the ruins.

First aid on the spot

Such was the enormous damage caused by the impact of the El Al 747 that a high death toll appeared likely and persistent rumours circulated to this effect. The ANP news agency reported that the city Medical Services had found the bodies of dozens of people who had jumped to their deaths from the higher floors. According to other rumours there were a large number of people in the buildings at the moment of impact. For several hours the media and members of the Co-ordination Centre were under the impression that 12 bodies had been recovered.

Medical teams, however, had relatively little work to do for the first few hours and at around 22.00 the Central Ambulance Station withdrew several dozen ambulances. By 22.40 a total of 36 wounded had been taken from the disaster area to nearby hospitals.

A large number of people needed help and support. Some of them were looked after at the disaster site, and were then taken by buses to one of the emergency relief locations. Other people were able to reach these locations on their own. On the Sunday evening, several places in the Bijlmer were spontaneously converted into relief stations for victims and local people but during the course of the evening, the spread of victims over several reception centres began to fragment relief activities. Hence, at around 23.30, the Co-ordination Centre – at the suggestion of the Southeast police district – decided that the Bijlmer Sports Centre would be the central reception point for all victims of the disaster.

The people in other reception centres were then bussed to the Sports Centre, where voluntary workers, city services and professional organisations assembled to provide relief and assistance. The police guarded the entrance to the Sports Centre and registered everyone who entered. The hall was besieged by camera crews and journalists, who were duly removed from the complex by the police. At around 03.00 on Monday morning, a large number of now homeless people were transferred from the Bijlmer Sports Centre to overnight accommodation elsewhere. Most of the approximately 200 homeless were taken to nearby naval barracks. Other overnight accommodation was arranged in the Social Services Department’s emergency facility. The relief workers stayed behind in the Bijlmer Sports Centre, together with some of the victims.

The Co-ordination Centre: initial activities

At first the Co-ordination Centre lacked any overview of developments in the disaster area. The scarce information available came from Fire Chief Ernst and Chief of Police Nordholt. It was known that the aircraft was not a passenger-carrying type, but there was minimal information on the dead and wounded. There was also a lack of clarity on the number of apartments affected. Once information had been obtained on the number of units involved, the City Population Register was directed to provide details on the number of people registered in the relevant units.

The Bijlmer air disaster was a shocking event, prompting reactions from around the world. City Hall was swamped by press representatives. Press conferences were held in City Hall, at 21.30 and 23.00. Despite the lack of available information, the national and international press was kept up to date as far as possible. At 22.30 Mayor Van Thijn, Fire Chief Ernst and Chief of Police Nordholt went to the site of the disaster to size up the situation for themselves. At midnight they gave together what was to be the first of a long series of press conferences.

From their position under City Hall, the Amsterdam authorities had regular contact with their counterparts at the provincial and national levels. After the crash, the Ministry of the Interior in The Hague had manned its National Co-ordination Centre, to assist the Amsterdam authorities if necessary. The North Holland provincial authorities established a crisis centre at Haarlem, where the Provincial Governor of North Holland, Van Kemenade, was kept informed on the situation in Amsterdam. Ministers Ms Dales (Interior) and Mrs Maij-Weggen (Transport and Public Works) were also briefed.

The first week

Recovery operations commence

Operations to recover human remains commenced at dawn on Monday morning. Precautions taken during the night ensured that conditions were safe enough for the rescue squads to enter the ravaged buildings. A mobile crane was used to remove loosely hanging concrete panels, one by one. Several different services were involved in the search through, and removal of, the rubble: the Amsterdam fire brigade and police, regional fire brigade units, members of the National Police Disaster Identification Team (the RIT), aviation experts, civil defence volunteers and various private contractors. The investigation into the cause of the crash ran parallel with recovery activities and concentrated on the missing flight recorder (the ‘black box’).

But, primarily, the operation was designed to recover and identify human remains. Recovery got off to a slow start as RIT’s painstaking approach took time, and the rubble of the flats and the aircraft wreckage could only be removed piecemeal. The pace of the recovery operation was largely dictated by the time-consuming process of identification. Other problems hindered the recovery operations. Small fires kept springing up in the ruins of the two buildings; smoke also hampered the teams’ work, while the risk of collapsing masonry remained.

Organisation of relief and assistance

On Monday, buses shuttled between the various places offering overnight accommodation and the day-time facility at the Bijlmer Sports Centre. In the course of the morning, many survivors of the crash collected in the sports hall. All those affected were registered on arr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The Bijlmer disaster – the events

- 2 Disaster response

- 3 In search of victims

- 4 In aid of survivors: psycho-social care

- 5 In aid of survivors: material relief

- 6 Crisis decision making: the Co-ordination Centre

- 7 Urban crisis management in Amsterdam: conclusions

- Appendix 1 Chronology of the Bijlmer Disaster

- Appendix 2 Notes on the population survey

- Appendix 3 Sources consulted

- Appendix 4 Interviewees

- Crisis Research Center