- 808 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cold Rolling of Steel

About this book

With the publication of this book, newcomers to the field of steel rolling have a complete introductionto the cold rolling process, including the history of cold rolling, the equipment currentlyin use, the behavior of the rolling lubricant, the thermal and metallurgical aspects of the subject,mathematical models relating to rolling force and power requirements, strip shape, and thefurth er processing of cold-rolled steel. The first book in print to examine in detail the three componentsof the cold-rolling process- the mill, the work-piece, and the rolling lubricant-this bookcan be used as a training manual and as a source for reference and research. The manuscript version of this book has already been in use as a textbookin courses on cold rolling and rolling lubrication and is now published for thebenefit of all in-training personnel-both operating and supervisory-in theprimary metals industry and for undergraduate and graduate students inmetalworking. The interrelationships of the three components, described in terms ofmathematical models, are of considerable value to engineers associated withprimary metals and metal research, to mill builders, and to electrical equipmentsuppliers. For plant metallurgists, the book relates product quality to operating conditions;for the steel user and purchaser, it affords insight into the variousprocesses associated with the manufacture of steel sheet and strip.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cold Rolling of Steel by Roberts,William L. Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 The History of Rolling

1-1 The Early History of Rolling

In its earliest beginnings, the rolling of flat materials was undoubtedly limited to those metals of sufficient ductility to be worked cold, and it is probable that it was first performed by goldsmiths or those manufacturing jewelry or works of art.● Yet, as is the case with many other important processes, metal rolling cannot be traced to a single inventor.† □

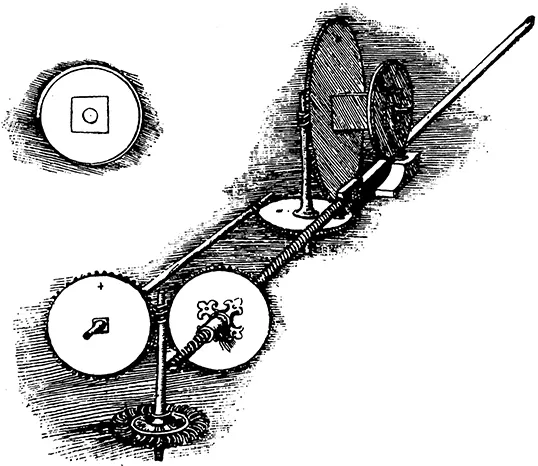

During the fourteenth century, small hand-driven rolls about half an inch in diameter were used to flatten gold and silver and perhaps lead. However, the first true rolling mills of which any record exists were designed by Leonardo da Vinci in 1480. (See Figures 1-1 and 1-2.) Sketches in his notebook show two mills, driven by worm gears, for rolling lead sheets and also a machine for producing tapered lead bars by means of a die and a spiral roll. Yet, there is no evidence that these mills were ever built, and there is a fair degree of certainty that metal rolling was not of any importance before the middle of the sixteenth century.

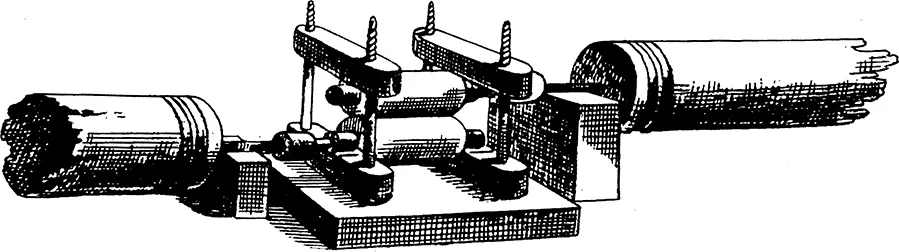

Figure 1-1

Sketches of a machine to roll lead for stained glass windows (drawn by Leonardo da Vinci).

Sketches of a machine to roll lead for stained glass windows (drawn by Leonardo da Vinci).

Before the end of the sixteenth century, however, at least two mills embodying the basic ideas of rolling are known to have been in operation. A Frenchman named Brulier in 1553 rolled sheets of gold and silver to obtain uniform thickness for making coins and mills for rolling mint flats were in use in 1581 at the Pope’s mint, in 1587 in Spain, and in 1599 in Florence.□ In 1578, Bevis Bulmer received a patent for the operation of a slitting mill which consisted of a series of discs mounted on two spindles, one above the other, in such a manner that the flat bar passing between the revolving discs was cut into strip. A mill of this type was set up at Dartford, in Kent, in 1590, by Godefroi de Bochs, a native of Liege, Belgium.

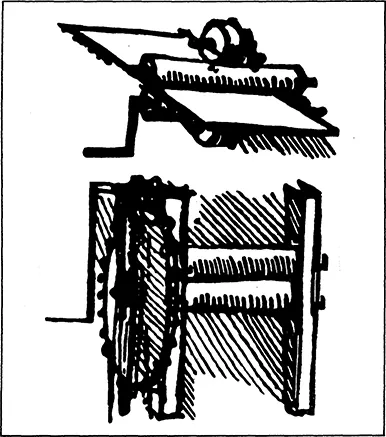

During the same period, lead was also beginning to find increasing use for roofing, for flashing, for the fabrication of gutters, and for other purposes. Salomon de Caus of France, in 1615, built a hand-operated mill for rolling sheets of lead and tin used in making organ pipes, the rolls being turned by a “strong-armed cross” attached to the lower axle as illustrated in Figure 1-3.●

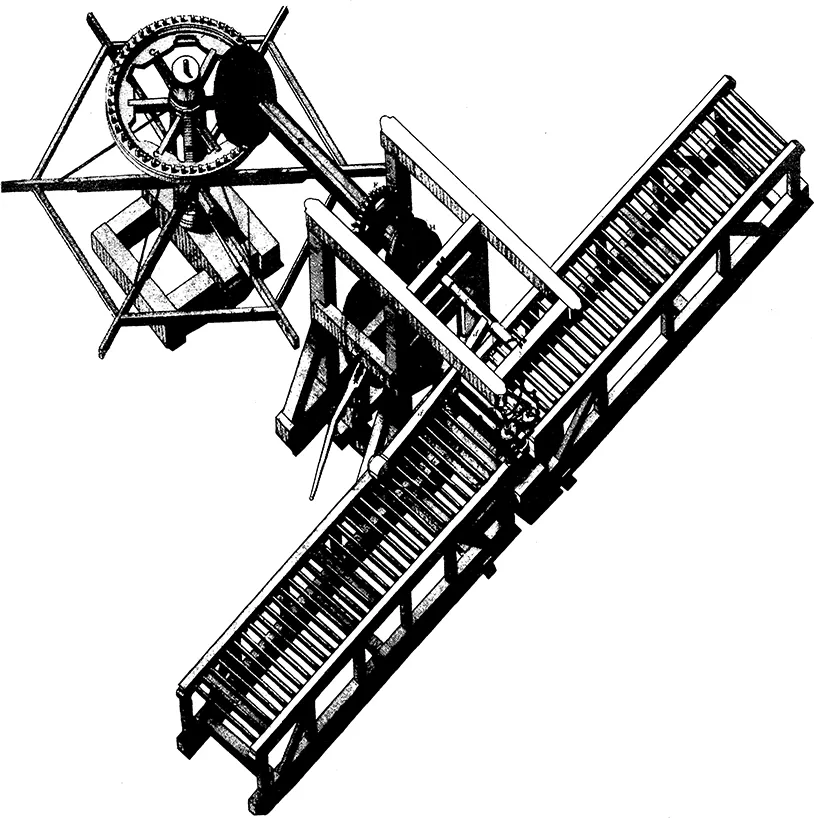

Figure 1-2

Sketch of a Rolling Mill by Leonardo da Vinci about A.D. 1495.

Sketch of a Rolling Mill by Leonardo da Vinci about A.D. 1495.

Figure 1-3

Mill Built by Salamon of Caus to Roll Sheets of Lead.

Mill Built by Salamon of Caus to Roll Sheets of Lead.

With the exception of the Bulmer slitting mill, mentioned above, all of these early developments pertain to the rolling of the softer metals, presumably at ambient temperatures. Johannsen, in “Geschichte des Eisens” says, “The use of rolls in an iron works was a German development of the 16th century. Belgium and England both started to use rolls about the same time, and they are both sometimes cited as the birthplace of rolling.” All three nations probably reached this development at about the same time, but there is little evidence of anything other than slitting mills in the 16th century, and still less evidence to give any nation a clear claim to priority. Such information as is available indicates that, in the rolling of iron, Great Britain led the way. No record of developments during the first half of the 17th century exists, but we know that in 1665 a rolling mill was in operation in the Parish of Bitton, near Bristol, and it is stated that, from 1666 on, iron was rolled into thin flats for slitting.†

The rolling of bars was foreshadowed during this period but was not brought to fruition. In 1679 a patent was issued covering the finishing of bolts by rolling, and in 1680 bars were being passed through plane-surfaced rolls to flatten out irregularities. A pamphlet on the “British Iron Trade” published in 1725 states, however, that even at that date all bars were hammered.†

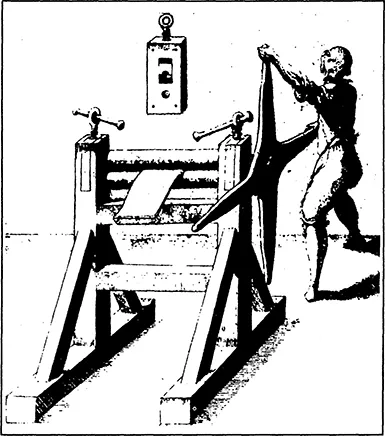

However, by 1682, large rolling mills for the hot rolling of ferrous materials were in operation at Swalwell and Winlaton, near Newcastle, England. Using these mills, bars were rolled into sheets and the sheets cut into rods at the slitting mills. Soon after this date, at Pontypool in Wales, John Hanbury began using at his ironworks a rolling mill as an independent machine for the production of thin sheet iron. Edward Llwyd, in a letter dated June 15, 1697 wrote, “One Major Hanbury of this Pontypool shew’d us an excellent invention of his own, for driving hot iron (by the help of a rolling machine mov’d by water) into as thin plates as tin … They cut their common iron bars into pieces of about 2 ft. long, and heating them glowing hot, place them betwixt these iron rollers, not across, but their ends lying the same way as the ends of the rollers. The rollers, moved with water, drive out these bars to such thin plates, that their breadth, which was about 4 in., becomes their length, being extended to about 4 foot, and what was before the length of the bars is now the breadth of the plate.”★

Although Major Hanbury designed the rolling mill described in the letter and illustrated in Figure 1-4, there is no evidence that he originated the idea of hot-rolling bars into thin sheets since it is believed that the practice was general throughout Europe by 1660 being known in Germany very early in the century. At any rate, Germany monopolized the growing English market for tinplate from shortly after 1620 until Major Hanbury began tinplate manufacture in this same Pontypool works sometime before 1720.■ After that, for more than 150 years, Wales was the major source of tinplate and terne plate.

Figure 1-4

John Hanbury’s Mill for Rolling Iron Sheets for the Manufacture of Tinplate (Sketch by Angerstein in 1755).

John Hanbury’s Mill for Rolling Iron Sheets for the Manufacture of Tinplate (Sketch by Angerstein in 1755).

During the early part of the eighteenth century, there is no doubt that rolling mills were in common use both in England and on the continent. Christopher Polhem (1720 – 1746), Sweden’s great mechanical genius, wrote of rolling mills at about this time and his writing indicates that he assumed his readers were familiar with them. Polhem himself designed a mill very similar to the modern Lauth mill, except that his mill utilized four rolls, with the backup rolls driven.

A “machine for rolling sheets of lead”, that really foretold the shape of subsequent rolling mills, was brought to France from England in 1728. This mill, shown in Figure 1-5, used rolls five feet long and twelve inches in diameter and was equipped with a roller table 24 feet long at front and back. It was a radical departure from the accepted mill design of the day, being a reversing mill, controlled by a clutch and gearing system. The plain rolls could be replaced with other, grooved rolls sixteen inches in diameter, with grooves ranging from four to two inches in diameter, with which hollow cast lead ingots were rolled into pipe over a mandrel.

In 1728, a patent for a mill to roll hammered bars “into such shapes and forms as shall be required” was issued to John Payne in England. However, Payne’s concepts (shown in Figure 1-6) do not appear to have been reduced to practice, but the rolling of iron bars and shapes was of interest to steelmakers and appears to have been practiced. For example, in 1747, the Academie des Sciences appointed a commission to visit a new mill at Essonne, France, which rolled iron bars.† By this time, the practice of polishing iron plates for tinning by cold rolling was also in vogue.□ In 1759, a patent was granted to Thomas Blockley of England for “polishing and rolling metals” — a broad description which really boiled down to rolls which the user could groove to suit his requirements; and in 1766, another Englishman, John Purnell received a patent for grooved rolls with coupling boxes and nut pinions for turning the rolls in unison. (See Figure 1-7.) Until this time, rolls were individually driven, and the unequal rates of revolution caused excessive roll wear, as well as making it necessary to install guides on both sides of each roll.

Figure 1-5

Rolling mill built in England and shipped to France in the early eighteenth century. (Illustration from “Machines Approvees par l’Academie des Sciences”, Published in 1728.)

Rolling mill built in England and shipped to France in the early eighteenth century. (Illustration from “Machines Approvees par l’Academie des Sciences”, Published in 1728.)

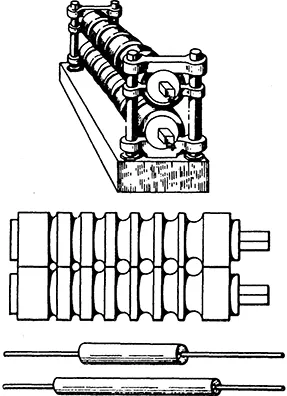

Figure 1-6

Rolls designed by John Payne in 1728 to produce round bars. (Illustration from “Machines Approvees par l’Academie des Sciences”. Edition published in Paris in 1728.)

Rolls designed by John Payne in 1728 to produce round bars. (Illustration from “Machines Approvees par l’Academie des Sciences”. Edition published in Paris in 1728.)

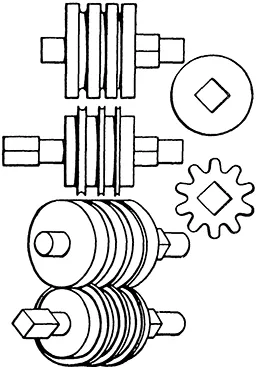

Figure 1-7

English patent issued to John Purnell in 1766 for grooved mills driven in unison by coupling boxes and nut pinions. (Staffordshire Iron and Steel Institute Proceedings.)

English patent issued to John Purnell in 1766 for grooved mills driven in unison by coupling boxes and nut pinions. (Staffordshire Iron and Steel Institute Proceedings.)

In this same period, the general appearance of these hot mills was beginning to change to the modern form. For example, the cast housing and the single screw each side of the mill were featured in English patent specifications filed by William Playfield in 1783.† (See Figure 1-8.)

Figure 1-8

English patent specifications filed by William Playfield in 1783. (Staffordshire Iron and Steel Institute of Proceedings.)

English patent specifications filed by William Playfield in 1783. (Staffordshire Iron and Steel Institute of Proceedings.)

In the manufacture of hand-forged plates for tinplating, it had been the practice to hammer several layers of metal at one time. Accordingly, when the rolling mill came into use for producing sheets for tinning, it became the practice, about 1756, to double the sheet after some elongation and then proceed with the further rolling of the two thicknesses of metal. Sometimes in this “pack rolling” or “ply rolling” the doubling was repeated so that four thicknesses of steel were rolled simultaneously.

The aforementioned hot-rolling mills consisted essentially of a single-stand of two rolls, one above the other. As described by Shannon,* “the operating principle of this type of hot mill consists briefly of the following steps: heat the piece, pass the piece through the rolls, push the piece back over the top roll with hand tongs, pass the piece through the rolls again, and so on until the piece being rolled either is of the required thickness or else has cooled down to the point where it must be reheated before the rolling can continue. This is only a bare outline of the elements of the operation, which is very much further complicated by matching (p...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- 1 The History of Rolling

- 2 Various Types of Cold Mills

- 3 The Components of Cold Rolling Mills

- 4 Mill Rolls and Their Bearings

- 5 The Instrumentation and Automatic Control of Cold Rolling Mills

- 6 Cold Rolling Lubrication

- 7 Thermal Aspects of the Cold Rolling Process

- 8 The Alloys of Iron, Their Physical Nature, and Behavior During Deformation

- 9 Mathematical Models Relating to Rolling Force

- 10 Torque Equations and Tandem Mill Control Models

- 11 Strip Shape: Its Measurement and Control

- 12 The Rolled Strip – Its Properties and Further Processing

- Name Index

- Subject Index