- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

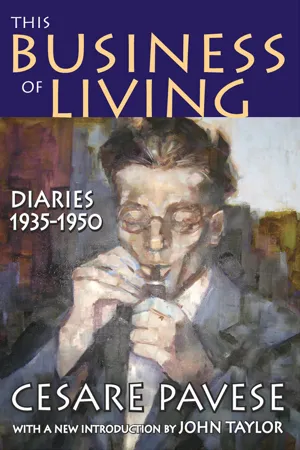

About this book

On June 23rd, 1950, Pavese, Italy's greatest modern writer received the coveted Strega Award for his novel Among Women Only. On August 26th, in a small hotel in his home town of Turin, he took his own life. Shortly before his death, he methodically destroyed all his private papers. His diary is all that remains and for this the contemporary reader can be grateful. Contemporary speculation attributed this tragedy to either an unhappy love aff air with the American film star Constance Dawling or his growing disillusionment with the Italian Communist Party. His Diaries, however, reveal a man whose art was his only means of repressing the specter of suicide which had haunted him since childhood: an obsession that finally overwhelmed him. As John Taylor notes, he possessed something much more precious than a political theory: a natural sensitivity to the plight and dignity of common people, be they bums, priests, grape-pickers, gas station attendants, office workers, or anonymous girls picked up on the street (though to women, the author could--as he admitted--be as misogynous as he was affectionate). Bitter and incisive, This Business of Living, is both moving and painful to read and stands with James Joyce's Letters and Andre Gide's Journals as one of the great literary testaments of the twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access This Business of Living by Cesare Pavese in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1935

Innermost Thoughts on My Work1

(October - December, 1935, and February, 1936, at Brancaleone)

The fact that some of my latest poems carry conviction in no way minimizes the importance of the truth that I compose them with ever-increasing diffidence and reluctance. With me, the joy of creation is sometimes extraordinarily keen, yet even that no longer matters much. Both these things can be explained by the facility I have acquired in handling metrical forms, which robs me of the thrill of hewing out a finished work from a mass of raw material, or by my concern with the practical aspects of life, which adds a passionate exaltation to my meditation on certain poems.

There is this to consider, too. More and more, the effort seems to me pointless, not worth while, and what is produced is either a harping on the same string or the fruit of prolonged searchings for new things to say, and consequently for new modes of expression. What gives poetry its intensity, from its very inception, is in reality a preoccupation with hitherto unperceived spiritual values, suddenly revealed as possibilities. I find my ultimate defense against this mad craze for novelty at all costs in my unshaken conviction that the apparent monotony and austerity of the style at my command may still make it the best medium for conveying my spiritual experiences. But such examples as I can find in history—if in the realm of spiritual creativeness it is permissible to dwell upon precedents of any sort—are all against me.

There was, however, a time when I had very vividly in mind a store of material—passionate and supremely simple, the substance of my own experience—to be clarified and interpreted in writing poetry. Every attempt I made was subtly, but inevitably, linked with that fundamental purpose, so that, no matter how fantastic the nucleus of each new poem, I never felt I was losing my way. I sensed that I was composing a whole that always transcended the fragment (of the moment).

The day came when my vital stock had been entirely used up in my works and I seemed to be spending my time merely in retouching or polishing. So true is this, that—as I realized more clearly after studying the work I had already done—I no longer troubled to seek for deeper poetic discoveries, as though it were merely a question of applying a skillful technique to a state of mind. Instead, I was making a poetic farce of my poetic vocation. In other words, I was reverting to an error that earlier I had recognized and avoided, (which is how I first learned to write with assurance and creative freshness), the error of writing poetry, even though indirectly, about myself as a poet. My reaction to this sense of involution is that henceforth it will be vain for me to seek a new starting point within myself. From the time when I wrote Marl del Sud, in which I first began to express myself precisely and completely, I have gradually created a spiritual personality that I can never, wittingly, set aside, on pain of nullifying or calling into question all my future hypothetical inspiration as a writer. In response, therefore, to my present feeling of impotence, I bow to the necessity for cross-examining my own mind, using only those methods which it has found congenial and effective in the past, and considering each individual discovery in relation to its potential importance. Granted that poetry is brought to light by striving after it, not by talking about it.

So far, I have confined myself, as if by caprice, to poetry in verse. Why do I never attempt a different genre? There is only one answer, inadequate though it may be. It is not out of caprice, but from cultural considerations, sentiment, and now habit, that I cannot get out of that vein, and the crazy idea of changing the form to renovate the substance would seem to me shabby and amateurish.

9th October

Every poet has known anguish, wonderment, joy. The admiration we feel for a passage of great poetry is never inspired by its amazing cleverness, but by the fresh discovery it contains. If we thrill with delight on finding an adjective successfully linked with a noun never seen with it before, it is not its elegance that moves us, the flash of genius or the poet's technical skill, but amazement at the new realities it has brought to light.

It is worth pondering over the potent effect of images such as cranes, a serpent or cicadas; a garden, a whore or the wind; an ox, or a dog. Primarily, they are made for works of sweeping construction, because they typify the casual glance given to external things while carefully narrating affairs of human importance. They are like a sigh of relief, like looking out of a window. With their air of decorative detail, like many-colored chips from a solid trunk, they attest to the unconscious austerity of their creator. They require a natural incapacity for rustic sentiment. Clearly and frankly they make use of nature as a means to an end, as something subordinate to the main issue, entertaining but incidental. This, be it understood, is the traditional view. My own conception of images as the basic substance of a theme runs counter to that idea. Why? Because the poetry we write is short; because we seize upon and hammer into some significance a particular state of mind, which in itself is the beginning and the end. So it is not for us to embellish the rhythm of our abbreviated discourse with naturalistic flourishes. That would be pure affectation. We can either concern ourselves with some other subject and ignore nature with all its fertile imagery, or confine ourselves to conveying the naturalistic state of mind, in which case the glance through the window becomes the substance of the whole construction. But with other kinds of writing, we have only to think of any vast modern work—I have novels in mind—and amid the usual medley of homespun interpolations due to our irrepressible romanticism we find clearcut instances of this play of natural imagery.

Supreme among ancients and moderns for his ability to combine the diverting image and the image-story is Shakespeare, whose work is constructed on an immense scale and yet is essentially a glance through the window. He evokes a flash of scintillating imagery from some dull clod of humanity and at the same time constructs the scene, indeed the whole play, as an inspired interpretation of his state of mind. The explanation lies in his superlative technique as a dramatist, embracing every aspect of humanity—and to a lesser degree of nature.

He has snatches of lyrics at his finger tips and builds them into a solid structure. He, alone in all the world, can tell a story and sing a song simultaneously.

Even assuming that I have hit upon the new technique I am trying to clarify for myself, it goes without saying that, here and there, it may contain traits borrowed in embryo from other techniques. This hinders me from seeing clearly the essential characteristics of my own style. (Contradicting Baudelaire, with all due respect, it may be said that not everything in poetry is predictable. When composing, one sometimes chooses a form not for any deliberate reason but by instinct, creating without knowing precisely how.) It is true that instead of weaving my plot development objectively, I tend to work in accordance with the calculated, yet fanciful, law of imagination. But to know how far calculation may go, what importance to attach to a fanciful law, where the image ends and logic begins, these are tricky little problems.

This evening, walking below red cliffs drenched in moonlight, I was thinking what a great poem it would make to portray the god incarnate in this place, with all the imaginative allusions appropriate to such a theme. Suddenly I was surprised by the realization that there is no such god. I know it, I am convinced of it, and therefore, though someone else might be able to write that poem, I could not. I went on to reflect how allusive, how all-pervading,1 every future subject must be to me, in the same way that a belief in the god incarnate in these red rocks would have to be real and all-pervading1 to a poet who used this theme.

Why cannot I write about these red, moonlit cliffs? Because they reflect nothing of myself. The place gives me a vague uneasiness, nothing more, and that should never be sufficient justification for a poem. If these rocks were in Piedmont, though, I could very well absorb them into a flight of fancy and give them meaning. Which comes to the same thing as saying that the fundamental basis of poetry may be a subconscious awareness of the importance of those bonds of sympathy, those biological vagaries, that are already alive, in embryo, in the poet's imagination before the poem is begun.

Certainly it ought to be possible, even for me, to create a poem on a subject whose background is not Piedmont. It ought to be, but hardly ever has been, so far. Which means that I have not yet progressed beyond the simple re-elaboration of the images materially represented by my innate links with my environment. In other words, there is a blind spot in my work as a poet, a material limitation that I do not want, but cannot succeed in eliminating. But is it then really an objective residuum or something indispensable in my blood?

11th October

Could all my images be nothing more than an ingenious elaboration of a fundamental image: as my native land, so am I? But then the poet's imagination would be impersonal, indistinguishable from the terms of comparison, regional and social, of Piedmont. The essence of his message would be that he and his country, regarded as mutually complementary, are beautiful. Is this all? Is this the fateful Quarto?2

Or, rather, is it not simply that between Piedmont and myself there runs a current of sympathetic impulses, some conscious, some unconscious, which I shape and dramatize as best I can: in image-stories? A relationship that begins with an affinity between one's blood and the climate, the very air, of home, and ends in that wearisome spiritual drift that disturbs me and other Piedmontese? Do I express spiritual things by speaking of material things, and vice versa? And this labor of substitution, allusion, imagination, how far can it be valued as an indication of that "allusive and all-pervading essence" of ours?

To counter any suspicion that my work may be merely a Piedmontese Revival, there are good reasons for believing it may broaden and deepen Piedmontese values. My justification for saying so? This. My writing is not dialectic. (How fiercely instinct and reason made me fight to avoid dialectism!) It refuses to be superficial—I paid for that by experience! It draws its sustenance from the strongest roots, national and traditional; it strives to keep its eyes on world trends in literature, and has been particularly aware of literary experiments and achievements in North America, where at one time I thought I had discovered an analogous development. Perhaps the fact that American culture no longer interests me in the least, means that I have outgrown this Piedmontese point of view. I think it does; at any rate the viewpoint I have had hitherto.

15th October

Yet we must have a new starting point. When the mind has grown used to a certain mechanical method of creation, an equally strong force is needed to get it out of that rut, so that, instead of those monotonous, self-propagating fruits of the spirit, it can produce something with a strange new flavor, sprung from a graft never tried before. Not that some external impetus can take the place of mental effort, but that one must completely transform the subject and the means, and so come face to face with new problems. Given a fresh starting point, the mind will, of course, regain its usual zest, but without some such springboard I cannot rise above my lazy habit of reducing everything to the pattern of an image-story. I need some outside intervention to change the direction of my instinctive lines of thought and so prepare them for fresh discoveries.

If I have truly lived these four years of poetry, so much the better: that cannot but help me towards greater incontestability and a better sense of expression. The first few times, it will seem to me that I have reverted to my own earliest days. It will even seem to me that I have nothing to say. But I must not forget how much at a loss...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- This Business of Living