- 412 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The I and Being Human

About this book

The'I' in the title pertains to the core of self that persists over time. These are challenges that elude people like social scientists, philosophers, or critics of literature and the arts, who would chronicle or explain humanity's doings. This informative, engaging, and joyous book by Norman N. Holland offers a usable model for the aesthetics, psychology, history, and science of the human subject.Holland begins by modeling the self as a theme and variations, constant yet constantly changing. He shows how symbolization, perception, cognition, and memory all contribute to the sense of I, hence how any one I grows out of a specific history and culture but also out of experiences all humans share.Holland proposes a scientific psychology based on his model, fusing the experiments of academic psychology with the insights of psychoanalysis. He illustrates his theory by the lives of George Bernard Shaw, Scott Fitzgerald, and other writers, as well as Freud's patient "Little Hans," in adulthood a famed stage director at the Metropolitan Opera. The I and Being Human attempts nothing less than to draw together aspects of the self, such as objectivity and subjectivity, that have eluded connection. In so doing, Norman Holland offers a rereading of psychoanalysis as a theory of the I.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The I and Being Human by Norman Holland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I| The Aesthetics of I

1|

Themes

and Wholes

Once upon a time, perhaps during the summer of 1900, Freud chanced to meet a young man. They chatted, and the young man began eloquently to protest his position as a Jew in Vienna at the beginning of this century. He declared his regrets that Austria had passed from a period of relative liberalism to one of reaction. Now Jews (like himself and Freud) were deprived of full freedom to develop their talents.

He waxed stronger and stronger on the theme, finally ending his speech with a line from Virgil’s Aeneid in which Dido, queen of Carthage, expresses her rage at her lover Aeneas who has abandoned her. She leaves her revenge, she says, to the Carthaginians who will follow: Exoriare— But then the young man could not remember the word that came next. He put together a semblance of the line by changing word order: Exoriare ex nostris ossibus ultor. Let an avenger arise from my bones! But at last, in some embarrassment he asked Freud for help. Freud supplied the missing word: Exoriare aliquis nostris ex ossibus ultor. Let someone(aliquis) arise as an avenger from my bones (1901b, 6:8–14).

At this point, the young man remembered some of Freud’s psychological work and his claim that one never forgets something without a reason.

Young Man: I should be very curious to learn how I came to forget the indefinite pronoun aliquis in this case.

Freud: That should not take us long. I must only ask you to tell me, candidly and uncritically, whatever comes into your mind if you direct your attention to the forgotten word without any definite aim.

Young Man: Good. There springs to my mind, then, the ridiculous notion of dividing up the word like this: a and liquis.

Freud: What does that mean?

Young Man: I don’t know.

Freud: And what occurs to you next?

Young Man: What comes next is Reliquien [relics], liquefying, fluidity, fluid. Have you discovered anything so far?

Freud: No. Not by any means yet. But go on.

Young Man: I am thinking [and he laughed scornfully] of Simon of Trent, whose relics I saw two years ago in a church at Trent. I am thinking of the accusation of ritual blood-sacrifice which is being brought against the Jews again just now, and of Kleinpaul’s book in which he regards all these supposed victims as incarnations, one might say new editions, of the Saviour.

Freud: The notion is not entirely unrelated to the subject we were discussing before the Latin word slipped your memory.

Young Man: True. My next thoughts are about an article that I read lately in an Italian newspaper. Its title, I think, was “What St. Augustine Says about Women.” What do you make of that?

Freud: I am waiting.

Young Man: And now comes something that is quite clearly unconnected with our subject.

Freud: Please refrain from any criticism and—

Young Man: Yes, I understand. I am thinking of a fine old gentleman I met on my travels last week. He was a real original, with all the appearance of a huge bird of prey. His name was Benedict, if it’s of interest to you.

Freud: Anyhow, here are a row of saints and Fathers of the Church: St. Simon, St. Augustine, St. Benedict. There was, I think, a Church Father called Origen. Moreover, three of these names are also first names, like Paul in Kleinpaul.

Young Man: Now it’s St. Januarius and the miracle of his blood that comes into my mind—my thoughts seem to be running on mechanically.

Freud: Just a moment: St. Januarius and St. Augustine both have to do with the calendar. But won’t you remind me about the miracle of his blood?

Young Man: Surely you must have heard of that? They keep the blood of St. Januarius in a phial inside a church at Naples, and on a particular holy day it miraculously liquefies. The people attach great importance to this miracle and get very excited if it’s delayed—as happened once at a time when the French were occupying the town. So the general in command— or have I got it wrong? was it Garibaldi?—took the reverend gentleman aside and gave him to understand, with an unmistakable gesture toward the soldiers posted outside, that he hoped the miracle would take place very soon. And in fact it did take place . . . [And he broke off.]

Freud: Well, go on. Why do you pause?

Young Man: Well, something has come into my mind . . . but it’s too intimate to pass on . . . Besides, I don’t see any connection or any necessity for saying it.

Freud: You can leave the connection to me. Of course I can’t force you to talk about something that you find distasteful; but then you mustn’t insist on learning from me how you came to forget your aliquis.

Young Man: Really? Is that what you think? Well then, I’ve suddenly thought of a lady from whom I might easily hear a piece of news that would be very awkward for both of us.

Freud: That her periods have stopped?

Young Man: How could you guess that?

Freud: That’s not difficult any longer; you’ve prepared the way sufficiently. Think of the calendar saints, the blood that starts to flow on a particular day, the disturbance when the event fails to take place, the open threats that the miracle must be vouchsafed or else. . . . In fact, you’ve made use of the miracle of St. Januarius to manufacture a brilliant allusion to women’s periods.

Young Man: Without being aware of it. And you really mean to say that it was this anxious expectation that made me unable to produce an unimportant word like aliquis?

Freud: It seems to me undeniable. You need only recall the division you made into a-liquis and your associations: relics, liquefying, fluid. St. Simon was sacrificed as a child—shall I go on and show how he comes in? You were led onto him by the subject of relics.

Young Man: No, I’d much rather you didn’t. I hope you don’t take these thoughts of mine too seriously, if indeed I really had them. In return I will confess to you that the lady is Italian and that I went to Naples with her. But mayn’t all this just be a matter of chance?

That last, gently evasive question expresses the doubts and confusions that have dogged psychoanalysis for the eight decades of its existence.

Against those doubts, however, stands the striking convergence that Freud’s explanation represents, two convergences, really. First, the young man himself became aware that something was on his mind of which he had been unaware. An unconscious idea became conscious. Second, the unconscious idea served as a centering theme around which Freud could fit the other themes of the young man’s associations.

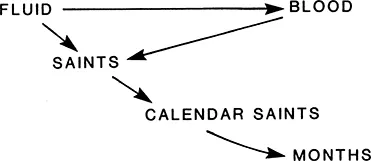

That is, his associations went: liquids—relics—Saint Simon—Jews vs. Savior(s)—Italian—St. Augustine—women—an “original”—(St.) Benedict—St. Januarius—blood flowing on a certain day. We could group these into two large themes: first, liquids, liquefying, flowing; second, relics and a series of saints. These two lines relate in form to the Latin syllable liqu—and in content this way:

Fluid, blood, saints, calendar, and months converge toward a centering theme of monthly bleeding. As Freud states his final interpretation:

The speaker had been deploring the fact that the present generation of his people was deprived of its full rights; a new generation, he prophesied like Dido, would inflict vengeance on the oppressors. He had in this way expressed his wish for descendants. At this moment a contrary thought intruded. “Have you really so keen a wish for descendants? That is not so. How embarrassed you would be if you were to get news just now that you were to expect descendants from the quarter you know of. No: no descendants—however much we need them for vengeance.”

Freud’s final formulation of the young man’s thought—I wish and I don’t wish for descendants—brings together not only the themes of liquis, liquid flowing, blood, and saints but also the particular word forgotten and the larger conversation around the theme of generations.

Freud began in the 1890s by taking seriously this kind of unifying interpretation of meaning in people’s symbolic actions. At the same time, he found he could enlarge and strengthen that kind of analysis by free association, nicely defined in his first words to the young man. Each of these techniques sustains and confirms (or disconfirms) the other. Association provides evidence for interpretation to unify. That unity then becomes a source of further associations, as the young man recalls a trip to Naples with his Italian lady friend. Together, association and interpretation make up the essence of psychoanalytic insight.

In form, Freud’s proof rests on probability. How many elements in the young man’s talk could he bring together and how directly and easily could he connect them?

At the same time, however, the proof of his interpretation simply happened. Indeed, there was no need for a proof. The young man’s sudden perception demonstrated the truth of what Freud had arrived at by reasoning alone.

In patient-therapist encounters whether face to face or across the analytic couch, I think psychoanalytic explanations usually draw on both these kinds of proof. In the first, the interpreter or explainer finds a way to create a verbal space between himself and the “other” in which they can each add and share words until they both feel convergence. “How could you guess that?” asked the young man. The second proof is less interpersonal and more formal. Eighty years after the event, I, a literary critic, can supply other themes for Freud’s explanation to bring together: that the young man knew he was “no saint,” that Origen castrated himself (thereby ending any possibility of descendants), or that “a-liquis” could be read as “without liquid.”

Indeed, we can see Freud himself trying such hypotheses with the young man, essaying a theme of saints as first names, the notion of Origen-origin, and “Paul in Kleinpaul” (literally, little Paul). He was evidently reaching for a theme having to do with “first” or birth or children (who are addressed by their first names), but he got little confirmation from the young man—the first sort of proof—and dropped it.

Characteristically, a psychoanalytic explainer draws on both the creation of a shared verbal space through free association and a thematic analysis of that space. The sharing provides the basis for cure, although one can use the technique to explain other, more casual events like this young man’s forgetting. The second move, thematic analysis, links psychoanalytic thought to many other disciplines. It is, however, quintessential to psychoanalysis. It deserves fuller treatment and its proper name:

Holistic Analysis

Freud imaged this kind of reasoning by a jigsaw puzzle: “If one succeeds in arranging the confused heap of fragments, each of which bears upon it an unintelligible piece of drawing, so that the picture acquires a meaning, so that there is no gap anywhere in the design and so that the whole fits into the frame,” then one has solved the puzzle (1923c, 19:116, see also 1896c, 3:205). As early as 1896 he compared this kind of convergence thinking to an archaeologist confronted with half-buried ruins, fragments of inscriptions, and the garbled traditions of the local inhabitants. His task would be to dig out as many additional data as he could and make them converge into a reading.

If his work is crowned with success, the discoveries are self-explanatory: the ruined walls are part of the ramparts of a palace or a treasure-house; the fragments of columns can be filled out into a temple; the numerous inscriptions . . . [may] yield undreamed-of information about the events of the remote past, to commemorate which the monuments were built. Saxa loquuntur! (1896c, 3:192; see also 1937d, 23: 259–60)

One feels that the very stones speak that theme which unifies all the data, and this is the sense one often gets that a holistic interpretation is self-evident.

We reason this way in everyday life, for example, when figuring out the function of an unknown device. Once I know that this conglomeration of clamp, crank, spikes, and blade is an apple-peeler, I understand that the clamp holds the device to a table, the spikes hold the apple, the crank turns it, and the blade shaves the skin off. In short, once I have grasped the central theme of peeling apples, I can use the theme to relate a host of otherwise baffling details.

We toy with this same kind of reasoning in detective stories. Listen to the immortal Sherlock Holmes at the end of “The Adventure of the Speckled Band.”

- “Well, there is . . . a curious coincidence of dates. A ventilator is made, a cord is hung, and a lady who sleeps in the bed dies. Does that not strike you?”

- “I cannot as yet see any connection.”

- “Did you observe anything very peculiar about that bed?”

- ”No.”

- “It was clamped to the floor. Did you ever see a bed fastened like that before?”

- “I cannot say that I have.”

- “The lady could not move her bed. It must always be in the same relative position to the ventilator and to the rope—for so we may call it, since it was clearly never meant for a bell-pull.”

- “Holmes,” I cried, “I seem to see dimly what you are hitting at.”

The good Dr. Watson evidently glimpses a theme: fixed physical connections leading from the stepfather’s room through the ventilator down the rope onto the heiress in her immovable bed. Holmes phrases this idea later as “a bridge for something . . . coming to the bed.” The idea of a bridge unifies these four details and their dates. Again and again, Holmes demonstrates this basic strategy of holistic reasoning: bringing clusters of details into mutual relevance around themes, until finally he infers that the doctor has been letting a swamp adder down the rope, hoping it will kill the heiress whose fortune he craves. The “solution” brings together both the details the distressed heiress told Holmes and Watson in London and those they have discovered “on the ground.”

Holmes also demonstrates—elegantly—two criteria for judging the validity of a holistic explanation: one quantitative, coverage, the other qualitative, directness. At first, Holmes mistakenly entertained a less viperous explanation:

When you combine the idea of whistles at night, the presence of a band of gypsies who are on intimate terms with this old doctor, the fact that we have every reason to believe that the doctor has an interest in preventing his stepdaughter’s marriage, the dying allusion to a band, and finally, the fact that [the surviving sister] heard a metallic clang, which might have been caused by one of those metal bars which secured the shutters falling back into their place, I think there is good ground to think that the mystery may be cleared along those lines.

The pattern of reasoning is the same, converging details toward a centering theme: the doctor somehow let the gypsy band through the shutters to do the sister in. That would interrelate the whistle, the clang, the presence of gypsies, the doctor’s finances, and the dying cry of “the band!” but not all the details (the ventilator or the bell-pull).

A good holistic explanation, like Holmes’s second, covers the relevant data. One can compare two interpretations quantitatively in the number of details they relate and qualitatively by the relative importance of those details (which in part depends on the quantitative effectiveness of the explanation). Holmes’s swamp adder explanation accounts for a great many more details than the gypsy hypothesis. Indeed, the second explanation renders the presence of gypsies relatively unimportant compared to more telling details like the ventilator linking the two rooms, the dummy bell-rope, or the heel-marked chair on which the villain stood. Having arrived at the ingenious idea of the swamp adder, Holmes comments on the earlier hypothesis: “ ‘I had,’ said he, ‘come to an entirely erroneous conclusion, which shows, my dear Watson, how dangerous it always is to reason from insufficient data.’ ”

Second, a holistic explanation that neatly and directly relates the details it covers satisfies us more than one that establishes only tenuous or devious connections. Holmes’s gypsy explanation simply says “the band” did something. The clang was caused by some movement of the shutters. With the second explanation, however, the phrasing “the band” is explained very exactly by the appearance of the snake, and “The metallic clang heard by Miss Stoner was obviously caused by her father hastily closing the door of his safe upon its terrible occupant.”

Holmes demonstrates other characteristics of holistic reasoning, notably the need to move away from categories and toward particulars. For example, the category “poisonous snake” does not account for as many details as the more particular “swamp adder” (poisonous plus speckled). The more general the category, the less it explains, like the biblical conclusion Holmes draws: “Violence does, in truth, recoil upon the violent.”

Because of this need for particulars, holistic research does not proceed by counting or by the repetition of experiments but by gathering more data. Holmes has to visit the scene of the death, where, having surmised that the ventilator ran from the victim’s room to the doctor’s, he can now see its size and position. He can find an iron safe to explain the clang. He can discover that the victim’s bed is clamped to the floor. Research leads to more data that require a stronger explanation, one that leaves no loose ends in the new, larger body of material.

To put one’s own mind actually to work in this kind of interpretation, the best exercise I can think of is a rather trivial one, a children’s game that was taught to me under the name of Puzzling Polly. The one who knows the game starts listing things that Puzzling Polly ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- Preface

- Part I The Aesthetics of I

- Part II A Psychology of I

- Part III A History of I

- Part IV A Science of I

- Appendix The I, the Ego, and the Je: Identity and Other Psychoanalyses

- Bibliography

- Index