- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1977, The Samurai has long since become a standard work of reference. It continues to be the most authoritative work on samurai life and warfare published outside Japan. Set against the background of Japan's social and political history, the book records the rise and rise of Japan's extraordinary warrior class from earliest times to the culmination of their culture, prowess and skills as manifested in the last great battle they were ever to fight - that of Osaka Castle in 1615.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Samurai by Stephen Turnbull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Gods and Heroes

When Heaven and Earth were one, and male and female were as yet unseparated, all that existed was a chaotic mass containing within it the germs of life.

Then appeared the shape of a reed shoot, which arose out of the chaos as the lighter, purer essence rose to form Heaven, while the heavier element settled down and became Earth. This mysterious form became transformed, as suddenly as it had appeared, into the first of the gods, Kuni-toko-tachi, ‘The Deity Master of the August Centre of Heaven’.

Other deities appeared, all of whom were born alone until the coming of a pair of deities, Izanagi and Izanami, ‘The Male who invites’, and ‘The Female who invites’. Together they stood on the floating bridge of Heaven and gazed down with curiosity upon the Earth as it floated beneath them. At the command of the elder deities they were given a coral spear ornamented with jewels, which they thrust into the Ocean and stirred its waters. Withdrawing the tip of the spear they allowed the water to drip from its point. The drops coagulated and formed islands, upon which one of which the heavenly pair descended, and raised the coral spear as the centre pole and foundation of their house. Japan was created.

This account of the beginnings of Japanese history is given in the oldest written records of Japan, the Koji-ki and the Nihongi, both of which were written in the early part of the eighth century A.D. In this creation myth we find the first statement of certain aspects of Japanese tradition, the most noteworthy being the divine ancestry of the Japanese rulers, and the appearance, right from the beginning of time, of the symbol, of a weapon. Had our anonymous chronicler wished to be a prophet as well as

a recorder, he could not have chosen more apt a metaphor for the following ten centuries, for until modern times the weapon of war, realized by the Japanese sword, was indeed to be the foundation of the house, and a pattern of struggle and armed conflict was to characterize its growth.

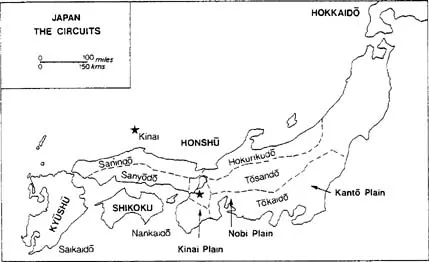

To some extent the seeds of conflict were sown right from the start, for the drops of water that fell from the spear coagulated in a most haphazard and untidy fashion. Instead of merging into one large piece of land they split into a myriad of tiny pieces, which appear to have joined rather grudgingly into four main islands. The largest of the four, which is called Honshū, arranged itself into the shape of an elongated crescent. At its southern tip appeared the tidier form of Kyūshū, which assumed a ragged western edge out of sheer spite. The simple island of Shikoku tucked itself in between the other two, to leave between itself and Honshū the long and beautiful waterway called the Inland Sea. The fourth island, Hokkaidō, coalesced at the cold northern tip of Honshū. So far north did this fall that it remained neglected until comparatively recent times, and plays no part in our history. Thus the reader need trouble himself with only three main islands, and a handful of minor ones that will be introduced as they enter the story.

In addition to a complicated shape, Japan was also given a challenging location. It is placed one hundred miles across the sea from the southern tip of Korea, with two of the little Japanese islands en route, narrowing the gap between the Japanese mainland and Korea to fifty miles. Now this is close enough to make a journey practicable, but not close enough to make it convenient. Thus the Japanese have been able to assimilate from Asia what they wanted, and to keep out what they did not. In the whole of the history of the samurai we will meet with only one case of foreign invasion. Incidentally we shall meet with only one case of Japanese aggression overseas, for wide moats work both ways.

In spite of these advantages the creators of Japan had indeed made a land fit only for heroes. The islands, by their very shape, ensured that communications would remain a problem. So it was with a peculiarly sly turn of mind that the deities ensured that 80 per cent of the land surface should be mountainous, of which nearly six hundred mountains should top 6,000 feet, and one, the legendary Mount Fuji, should rise to 12,000. Place upon these mountains a rich vegetation, with many a swift flowing river and clear lake, and add a climate that gives sharply defined seasons of warm humid summers and snowy winters, dramatic springs and melancholy autumns. Collect the remaining 20 per cent of fertile land into but three main areas, and arrange for the occasional typhoon and earthquake just to remind the natives of the Creators' unseen hand, and you have a country that from today's aircraft gives the impression of wrinkled brilliant green velvet. Yet, in the period of time we are discussing, merely to keep alive must have been an adventure.

The three great areas of fertile land lie along the eastern edge of Honshū. The largest is the Kantō plain, covering about 5,000 square miles. The others are the Nobi and the Kinai plains. The struggle for possession of these lands is the key to Japanese history. Throughout the ages these flatlands have attracted the bulk of the Japanese population, and they now carry the great metropolises of Tōkyō, Nagoya and Ōsaka respectively.

The Kinai plain, by its position in the centre of Honshū, has tended to become the ‘hub’ of Japan, as Lake Biwa, whose northern shores lie among mountains and which empties into the sea, neatly divides Japan into two. Furthermore, until modern times the capital has always been situated in the Kinai, so that it has become known as the area of the ‘Home Provinces’. Throughout this book the terms ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ Japan refer to these directions from the Kinai. For many years the main lines of communication in Japan have been along the coasts, either westwards along the Inland Sea to Western Honshū, Kyūshū and Shikoku, or east and north along the famous Tōkaidō, the ancient highway made famous by the artist Hiroshige and his series of wood-block prints. Having thus set the scene, let us return to the gods.

We do not have to read far into the ancient chronicles before we find mention of the first actual sword in mythology. This weapon belonged to Izanagi. He used it to kill his son the Fire God, whose birth had caused Izanami extremes of pain. Izanami was so distraught that she abandoned Izanagi and crept away into the Underworld. Filled with remorse at the accomplishment of the first murder, and grieving for his wife, Izanagi, like Orpheus, followed her, to rescue her from the clutches of the gods of Hell. His attempt proved unsuccessful, and he was pursued on his return journey by the Eight Thunder Deities and other assorted unpleasant spirits, against whom he wielded the sword with deft skill. After his return he performed numerous ablutions to rid himself of the pollution of Hades.

The Fire God had not been their sole offspring, for two deities had preceded him. The eldest was Amateratsu, the Goddess of the Sun, who was followed by Susano-o, the ‘Impetuous Male’. Susano-o appears to have been an unsettling companion, given to fits of temper which he enlivened by tossing thunderbolts across the sky. During one of his tantrums his gentle sister became so alarmed by his violent behaviour, which included flinging a dead horse at her, that she fled from his sight and locked herself in a cave. At this all the people of the world were much distressed, for with the Sun Goddess hiding away the world had been plunged into darkness. So they conferred together as to the best way of enticing her out again and hit on the idea of making her the most beautiful gifts imaginable.

A certain ‘One-Eyed Deity’ as he was called, forged an iron mirror. This heavenly craftsman is traditionally regarded as the father of the art of sword-making, and it is interesting to note that the one-eyed Cyclopes of Greek legend were also famous for their metal-working.

The other gift was a necklace of precious jewels which, together with the mirror, was hung on a tree at the mouth of the cave. By the sound of dancing and laughter Amateratsu was induced to peep round the edge of the stone at the cave's entrance, where she caught sight of her features reflected in the mirror. Her own beauty made her stop and stare, and before she had a chance to return to the cave its mouth was blocked completely. So was light restored to the world.

On at least one occasion, however, Susano-o's violent ways were put to good use. In the province of Izumo lived a great serpent, with eight heads and tails, and its tails filled eight valleys. Its eyes were like the sun and the moon, and on its back grew forests. This serpent, who swallowed people, had a particular taste for young maidens. Susano-o undertook to kill the serpent. Choosing an attractive young maiden as bait, he lay in wait for the serpent, his father's sword in his hand, and with a prodigious quantity of sake (Japanese rice wine) as an added enticement for the monster. Eventually the serpent came, ignored the maiden, and stuck its eight heads into the sake, which it drank with relish. Before long the beast was intoxicated, and an easy prey for Susano-o, who furiously began to hew it to pieces. When he reached the serpent's tail, however, his blade was turned, and he discovered a sword hidden there. As it was a very fine blade he took it and presented it to his sister, and because that portion of the serpent's anatomy had been covered with black clouds he called the sword ‘Ame no murakomo no tsurugi’ or ‘Cloud Cluster Sword’.

As the first born, Amateratsu had inherited the Earth, and some time afterward sent her grandson Ninigi to rule over the islands of Japan which her parents had created. When Ninigi was about to leave Heaven she gave him three items that would ease his passage through the world - the mirror, the jewels, and the sword. Thus armed with the objects that were to become the Japanese Crown Jewels, Prince Ninigi descended from Heaven to the top of Mount Takachiko in Kyūshū. He married, and eventually passed the regalia on to his grandson Jimmu, the first earthly Emperor of Japan.

In Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado, Pooh Bah claims to be able to trace his ancestry back to a ‘protoplasmal primordial atomic globule’. Perhaps Gilbert knew of the Japanese creation myths, describing the emergence of life from a shapeless chaotic form; but, satire notwithstanding, the present Emperor of Japan can look back on 124 Imperial ancestors, the oldest established ruling house in the world. Admittedly the existence of Jimmu, the first Emperor, is very doubtful. According to legend Jimmu took sword in hand and left Kyūshū for Honshū, fighting many fierce battles on the way against all manner of foes, including eighty earth spiders, who were speedily vanquished, once again, with the help of liquor. He ascended the throne of Japan on the traditionally given date of 11 February, 660 B.C., which is still celebrated in Japan with a public holiday.

The more down-to-earth but no less violent testimony of archaeology tells of the existence of man in the Japanese archipelago for the past 100,000 years. For the first 90,000 years Japan was linked to the main land mass of Asia. Then the oceans were swelled by the melting of the glaciers of the last ice age, and Japan was cut off from Asia by the straits that were to have such an influence on her later history.

In the now isolated Japan lived the Japanese aborigines and from about 500 B.C. they began to be supplanted by the Mongolian type of people associated with modern Japan. They arrived gradually over the next few hundred years, bringing with them the potter's wheel, bronze, iron and the cultivation of rice. Their sharp iron swords, which within a few generations were to become the most deadly examples of their art, helped the invaders push back the indigenous tribesmen. Some interbreeding certainly took place, and they are probably responsible for the relative hairiness of the Japanese compared with other Mongoloid peoples.

By the time of the tenth Emperor, Sujin (c.A.D. 200), the mythological accounts were beginning to combine with a primitive animism later regarded as Japan's indigenous religion of ‘Shintō’ – ‘The Way of the Gods’. One essential of Shintō is that certain places, perhaps waterfalls, mountain tops or rock formations possessing unusual beauty or grandeur, are the abodes of the gods. Such places became a focus for Shintō worship, and it was more than likely that a Shintō shrine would be built there, instantly recognizable by the characteristic gateway, the ‘torn’, shaped like the Greek letter π. Under Shintō all the universe was united, and the holy places were a corner of creation where man might identify with nature and adore the makers of it. Shintō offered no great interpretation of the world, but invited man to partake in it by associating himself with the natural phenomena of trees, earth, water, birth, life and death.

This attitude of harmony with nature is nowhere shown better than at Sujin's foundation of the Grand Shrines of Ise, built to serve as a centre of worship of Amateratsu the Sun Goddess. The remarkable complex of buildings is of the utmost simplicity of construction, and to emphasize the fact that they are not a permanent monument but a living part of their environment, the Shrines have been demolished and rebuilt every twenty years since their foundation.

Not unnaturally the Shintō tradition is closely associated with the enduring institution of the emperor, who claims descent from the deity of Ise. Thus the foundations of Ise have been especially revered by the Japanese people, and as we shall see in later chapters, in times of national crisis it is to Ise that they have turned.

Emperor Sujin is also noteworthy for two other innovations. Faced with the threat of rebellion, he appointed four generals to lead armies to the four quarters of the country. The generals were each given the title ‘Shōgun’ (roughly translatable as ‘Commander in Chief’), the first time in Japanese history that this word, which is to achieve such importance in the years to come, was used. Sujin's other innovation was simpler but no less dramatic. He invented income tax!

Sujin was followed by emperor Keikō, whose son now demands our attention. This character, Prince Yamato, represents a transitional stage between gods and heroes. He is, in a way, a forerunner of the samurai heroes of later times. He still fights monsters, but possesses entirely human characteristics, and it is worth examining the Yamato legend because of the pattern he set for the samurai tradition. ‘He’ may be a misnomer, for Yamato is probably a composite character, whose exploits, suitably embellished and exaggerated, are those of the many warriors sent out on expeditions in the early centuries of the Christian era.

In bravery Yamato equalled any knight of the Round Table, but the chivalric spirit is conspicuous by its absence. Yamato's career as a swordsman began by the murder of his elder brother as a punishment for being late for dinner. This so shocked his father, the Emperor Keikō, that Yamato was despatched to Kyūshū, where he might put his warlike energies to some use by opposing the enemies of the throne. Before setting out, the youth visited his aunt, the high-priestess of the Great Shrine of Ise, who presented him with the sacred sword ‘Cloud Cluster’. However, it was a trick, and not swordsmanship, that encompassed Yamato's first victory of the campaign. He arrived at the house of his enemy and observed that it was heavily guarded, while there was much activity within in preparation for a banquet. The Prince thereupon disguised himself as a girl and joined in the merry-making, sitting between the two chieftains who were gradually becoming intoxicated. When they least suspected it, Yamato drew the sword from his robe and slew them both.

His mission accomplished, Yamato set off for home, stopping on the way to subdue another local chieftain in the province of Izumo. Once more he resorted to trickery to attain his ends. He first cultivated the friendship of the chieftain, to the extent of establishing a strong bond between them. Then he secretly manufactured a dummy sword of wood, which he wore in his belt. One day he invited the chieftain to bathe with him in the river. They left their swords on the river bank, and on emerging from the water Yamato suggested that they exchange swords as a further pledge of friendship. This his comrade readily agreed to do, and also responded to Yamato's challenge to a friendly duel with their new swords. Of course the luckless chieftain soon discovered that the sword he now held was of wood, and Prince Yamato cut him down with ease.

So far Prince Yamato seems a most unattractive hero, and quite unlike the ideal of the samurai warrior. But after his return home his character appears to change, and he becomes the archetype of the wandering hero who dies an early and tragic death, a theme to be repeated time and again in the history of the samurai.

As Yamato set out on his travels once more, the great serpent slain by Susano-o, miraculously restored, appeared in front of him on the road, and demanded the return of the sword Cloud Cluster. Yamato merrily jumped over the serpent and continued on his way. The only other interruption to Yamato's progress was a beautiful maiden named Iwato-hime, with whom he fell intensely in love. He finally managed to drag himself away from her, and proceeded on his way in the direction of Mount Fuji. Here some enemies invited Yamato to join them in a stag hunt, and when he was engrossed in the chase they set fire to the long grass in order to burn him to death. So the Prince drew Cloud Cluster from its scabbard and, swinging it furiously about him, cut his way through the burning grass to safety. Thus Cloud Cluster came to be known as ‘Kusanagi no tsurugi’ (‘the Grass-mowing Sword’).

After this narrow escape he returned to Iwato-hime. But realizing that he could not stay for ever, Yamato left as a memento his most treasured possession, Cloud Cluster or Grass-mower, which Iwato-hime tearfully took and hung from the branches of a mulberry tree. Now the great serpent, resentful that Yamato had escaped him, was lying in wait for the hero on his return journey. Yamato paid no more heed to the monster than on the former occasion, but sprang clear over him and passed on. This time, however, the tip of his foot touched the serpent as he leapt. Before long he was seized with a fever that spread through his whole body. He managed to obtain some relief by bathing his foot in a cool stream, but though the fever subsided the sickness was still with him and he collapsed.

As the prince lay on his sick bed he longed to see Iwato-hime once again. Suddenly his eyes fell upon her, for she had followed him on his journey. Thus were his spirits temporarily raised, but his condition was rapidly deteriora...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Author's Preface

- Foreword

- List of Illustrations

- Conventional periods of Japanese history

- 1. Gods and heroes

- 2. Buddha and Bushi

- 3. The Gempei War

- 4. The fall of the house of Taira

- 5. Their finest hour

- 6. Acts of loyalty

- 7. The age of the Country at War

- 8. Saints and samurai

- 9. Tea and muskets

- 10. Hideyoshi's Korean war

- 11. The final reckoning

- 12. Decline and triumph

- Appendix 1. Selected genealogies

- Appendix 2. Chronological list of Shōguns

- Bibliography

- Index