eBook - ePub

Art of Constructivist Teaching in the Primary School

A Guide for Students and Teachers

- 103 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 1999. This book arose from a growing awareness of student teachers' need for an easy, informative and inspiring book about the constructivist approach. On hearing that label, students tend to react either with, 'Isn't that marvellous - the answer to all my problems', or 'Sounds fine in theory, but I couldn't do it'. Both are wrong. This book may help to get the balance right.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Art of Constructivist Teaching in the Primary School by Nick Selley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

General Theory

General Theory

Each of us can only learn by making sense of what happens to us through actively constructing a world for ourselves.

Douglas Barnes (Oracy Project)

CHAPTER 1

Constructivist Learning

The constructivist approach to primary education is not a new type of curriculum. It is an approach, or a teaching method. It can be used to augment, partially to replace, and usually to improve existing classroom methods.

For student teachers especially, I must stress that a constructivist approach is compatible with any curriculum, as required by any school; but of course the extent to which it can be utilised will vary according to the ethos of the school. The more the children’s own learning (rather than the content of the curriculum) is given priority, the more successful will be the adoption of constructivist teaching.

To start with, let’s try to give a rough idea of what constructivism is. At one level, it is a theory of learning which holds that every learner constructs his or her ideas, as opposed to receiving them, complete and correct, from a teacher or authority source. This construction is an internal, personal and often unconscious process. It consists largely of reinterpreting bits and pieces of knowledge – some obtained from first-hand personal experience, but some from communication with other people – to build a satisfactory and coherent picture of the world. This ‘world’ may include areas which are physical, social, emotional or philosophical.

This view of learning is already well known, in the simple sense that (in the words of Douglas Barnes 1992: 123), ‘each of us can only learn by making sense of what happens to us through actively constructing a world for ourselves’. The crucial question is: what is an appropriate role for the teacher in helping a pupil to construct a successful model of the world? This will be examined in Chapter 3.

An immediate, although negative, significance of constructivism for the teacher is that it suggests that traditional ‘transmission’ teaching, typified by the lecture, the sermon, and the textbook, may be a very inefficient method. Much of what is ‘taught’ (i.e. sent out towards the student) will be misconstrued, garbled, or ignored. Most of us can recall the experience of failing to learn what someone has been teaching. Sometimes it has gone on, either tediously or frustratingly, for years.

A better way would be for the teacher to find out, or make an estimate of, what the student already knows about the subject, and start from there. This would avoid the boring repetition of what was already thoroughly known; and the futility of teaching information that was incomprehensible. Ideally, the teacher should help the learners to develop their existing ideas and concepts. This will involve working with (rather than sidelining) these ideas: examining their applicability and effectiveness, and suggesting small, manageable improvements. To get to this position, the teacher needs to know of some techniques for drawing out or eliciting pupils’ ideas. This will be discussed in Chapter 2.

Then, after elicitation and formative assessment leading to a rough picture of the various pupils’ ideas, the teacher will need to use appropriate pedagogical techniques. The aim is to encourage pupils to expand and refine their conceptual powers (I say ‘encourage’ rather than ‘teach’ here, because personal growth cannot be forced. ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink’).

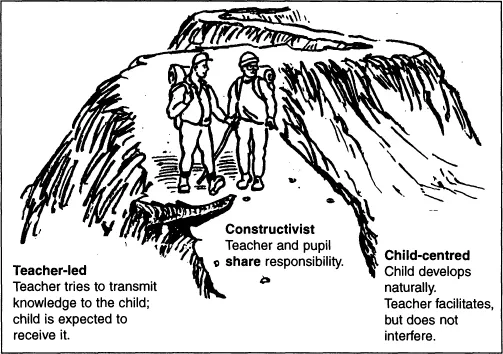

Compared to the transmission mode, the constructivist approach is child-centred. But this is not to suggest that the teacher just sits on the sidelines while the child ‘grows’. On the contrary, constructivist teaching requires the teacher to take a very active role, and one which calls upon expertise, knowledge, and professionalism. It is a middle way, but also a higher way than either the didactic transmission mode or unguided discovery. I have attempted to represent this by analogy with a way along a ridge (Figure 1). The associated danger of falling off, one side or the other, is a known feature of such paths.

Figure 1 The constructivist approach is a middle way – and a higher way.

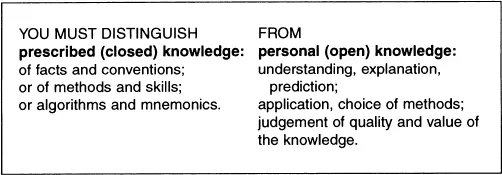

The constructivist approach is not appropriate to all school learning. Some knowledge, if it is of the factual kind, or defined by convention, may need to be transmitted directly; for in such cases, creativity or personal imagination are not required, and any alteration would not be beneficial. Examples might include learning the alphabet, spelling, the rules of punctuation; the symbols used in arithmetic; the points of the compass; and the national anthem.

However, much rote learning is of vocabulary – words which refer to particular ideas. The names are easy to learn once the child knows what they refer to, but an unrewarding chore otherwise. For example, it would be misguided to try to teach the names North, North-east, East etc. to a young child who had no sense of direction, and was still unsure even of right and left. So it might be wise to use constructivist methods to determine whether the children were ready for learning certain things, even if these seemed merely factual.

Figure 2 A classification of knowledge. Transmission methods may be used for teaching prescribed knowledge, but not for personal knowledge.

It might be useful now to state what constructivist learning is not. It is not just any pedagogy which involves the pupils in activity and participation, for sometimes this activity does not contribute to the construction of knowledge. Examples of non-constructivist ‘active learning’ include: (a) science practical work based on following instructions; (b) ‘gap-filling’ exercises, with the missing words listed at the base of the worksheet; (c) pictures to label; and (d) information to extract from a text. I would exclude all these because, despite the activity, the learner is being allowed no part in deciding what it all means. The teacher keeps control of that, and uses ticks and crosses to enforce compliance.

To sum up, the constructivist approach is not:

• just the provision of tasks for pupils to engage in;

• a ‘project’ in which predetermined information has to be found (e.g. in books, CD-Roms, or museums);

• a practical activity conducted according to a predetermined method, even if this is called an ‘investigation’ (unless, that is, the objective is for the children to discuss and interpret, entirely freely, the results which they obtain);

• the kind of lesson which leads children to an achievement which is exactly what the teacher expected.

But the constructivist approach is an ideology that places emphasis on the meaning and significance of what the child learns, and the child’s active participation in constructing this meaning.

It is important for every teacher, with any sympathies for constructivism, to be very clear as to its theoretical and evidential base, not only because this is likely to enhance the effectiveness of that teaching, but also because of the likelihood that the method will have to be defended against misconceived attack (see also Chapter 5). As Andrew Davis put it (Davis & Pettitt 1994: 3), ‘Views of teaching and learning held by politically influential groups are in stark contrast to constructivism, and in such a climate it is especially important to be able to support practice with a coherent and readily justifiable theoretical position.’

CHAPTER 2

Children’s Alternative Ideas

I shall first consider ways by which a teacher can get to know what any individual child’s presuppositions are, about some given topic. Clearly the most obvious way, though not the most commonly practised, is actually to listen to what the child has to say about it. This is most effective after the child has had some opportunity to think about the subject: possibly through a question or task, tackled without haste. The elicitation of ideas will probably need either a quiet moment alone or a small group discussion. It is well worth the trouble to tape-record these conversations, to aid the memory.

The problem of recording the ideas of the whole class at once, with children who are not fluent at writing, is often solved through drawing. Most children are willing to make an attempt to express their thoughts in a drawing, and the teacher can then use this as a starting point for further probing, by private conversation in the classroom. The extra information elicited in this way can easily be written on the page, either alongside the drawing, or as labelling for parts of it.

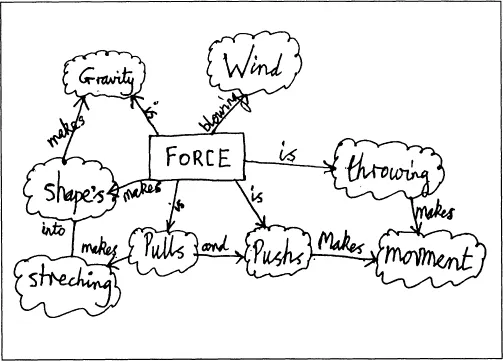

A similar device, to help children to capture their thoughts on paper, is the ‘concept map’. Firstly you should produce a set of words related to the topic, either chosen in advance, or generated through a ‘brainstorming’ session. The pupils start with one significant word, and write it in the middle of a blank sheet of paper. They then choose a second word, which they can relate meaningfully to the first, and write it nearby. Both words are placed in boxes, which are joined by a line. Older children may then write, along the line, what the relationship is. (Younger ones will communicate this orally.) Then further words are added to the ‘map’, until all meaningful links have been shown. As with the drawings, it is generally necessary to ask the child for a verbal expansion of the ideas captured on the map.

Every child’s ideas will differ, to some extent, from those of any other child. However, it is found that there are often sufficient resemblances to make it worthwhile to select some of the more typical ideas. A teacher, having elicited responses from her class, will naturally spot the most common contributions, and may also make a rough count of those which are approaching, or still far from, the approved version.

Figure 3 A concept map produced by a Year 6 child, from Comber and Johnson (1995).

Published research

The teacher will be severely limited by time (both for collecting full and detailed accounts, and for the analysis), and by the small size of the population being studied. However, educational researchers have been engaged in this kind of activity for many years, and have collected a wealth of data, especially in the science area. Their methodology has usually been one of the following, and I shall briefly consider the advantages of each:

1. Written tests, usually requiring short answers, but sometimes including completion of drawings or diagrams. The advantage is that these can be administered to large numbers of children, in pursuit of statistical reliability – that is, assurance that the results are typical for the population being tested. The disadvantage is that the children’s responses are often ambiguous or unclear, and there is nothing that can be done to sort this out. There is no way of distinguishing between a child who genuinely holds an unusual view, and one who merely misread the question.

2. Requests to children to make drawings (sometimes annotated by the child or, for slow writers, by dictation to an adult) showing their ideas on a given question. This method requires more time, because every child must be visited by an adult before the task can be considered finished, to check on what the child has interpreted the task to be, and what the drawing represents. The advantage of this method is that it is open-ended, and often elicits individual ideas which the teacher/researcher had not imagined, and would not have been asked about in a pre-set test.

3. Semi-structured individual interview. This last method usually takes place after familiarization activities, and the questions are focused on real objects or drawings showing situations which require explanations. The interviewer has a prepared set of questions, but is ready to follow up any unexpected or novel ideas which emerge in the child’s answers. The conversations are recorded, and considerable time and labour will be required to transcribe and analyse these (see Selley (1995 and 1996) for examples). The advantage is that if the interviewer can gain the child’s trust, then genuinely held beliefs can be uncovered. It is also possible to distinguish stable, firmly-held ideas from guesses or hastily produced responses. All this useful revelation will come about only if the child is sure that the occasion is not like a test, and that her/his own views will be accepted and respected. In this regard the interview resembles a conversation.

The originator of this area of study was Jean Piaget, who was particularly interested in the development of rationality in the child. The wide range of topics which he studied included growth, movement, the material world, chance and probability, proportion and morality. After some decades of neglect, inter...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I General Theory

- Part II Specific Subject Studies

- Part III A Philosophical Overview

- References

- Index