![]()

Chapter 1

Overview

This book is for people involved with oil as consumers, competitors, commentators, investors, managers, politicians and regulators. It examines corporate, social and environmental challenges and argues that the chief concern about oil over the next 20 years will be its acceptability, not its availability. The book reviews conventional energy projections, focusing on issues of transportation, oil reserves and growing markets for gas. It argues that there is unlikely to be any sustained increase in fossil fuel prices over this period. Traditional ‘oil’ issues such as security are giving way to ‘new’ issues such as environmental and social behaviour in a context of changes in technology and increasing the globalization of competitive markets for all types of energy. The resulting challenges for the industries concerned, for national governments and for value-driven non-government groups are identified.

The key messages of the chapters are as follows:

1 Overview: So much change deserves a new perspective.

2 The conventional vision: Public projections of the role of oil are analysed in the benign scenario of continuing strong economic growth over the coming 20 years with some loss of market share to natural gas.

3 Oil supply: The relative abundance of oil and its uneven distribution form the basis for continued competition among producers. An aggressive oil price cartel cannot be sustained by exporting governments.

4 Transport in transition: Competition among alternative technologies for road transport is likely to intensify as 2020 approaches. New choices of transport fuel will be involved in the competition between vehicle manufacturers; new approaches to the offer of transport services will be tried.

5 Gas for oil markets: Gas is the new frontier for oil consumers and private sector oil companies. Growth is uncertain in many developing countries because of the need to invest in cross-border infrastructures. There is a possible contradiction in the conventional vision of gas gaining a greater share of energy markets across the world while it also increases in price relative to oil.

6 Oil prices – the elastic band: Competition will force oil prices to fluctuate between a lower limit determined by exporters’ resistance to economic disaster and a ceiling which is kept down by competition from other fuels and technologies of demand.

7 Energy security: Objectives and instruments need to be redefined: the key economic concerns for importers are managing the effects of disruptions and minimizing long-term energy costs, not minimizing their energy imports. The threat of political sanctions has been reversed. It is exporting countries that now need to be concerned about sanctions aimed at their domestic and foreign policies by governments and public opinion in developed countries.

8 Environment and social acceptability: The Kyoto Protocol is a step towards internationally agreed policies to limit the growth of fossil fuel consumption but its quantitative approach, obsolescent baselines and limited geographic scope mean that other measures will be necessary. Upstream, energy projects face increased opposition through private international channels to limit the ecological, social and political damage caused by high-impact development projects in poor or weak countries.

9 Challenges and choices: The risks and choices for companies, governments and advocates of social values are different, although they are interconnected. They are differently affected by the risks in the ‘conventional vision’ for oil, and by conflicts over the acceptability of oil use and development. Understanding the differences is the first step to identifying the scope for mutually interesting actions.

![]()

Chapter 2

The conventional vision

This chapter analyses the current (mid-2000) ‘business as usual’ or ‘reference case’ scenarios of energy and oil trends to 2020 of the three main agencies that expose their projections – and their methods – to public scrutiny.1 These are:

- the European Commission (EC), through its 1999 ‘Shared Analysis’ based on the POLES model of the Institut d’Economie et de Politique de l’Energie, referred to here as EC (POLES);

- the Energy Information Agency (EIA) of the US Department of Energy, in its annual International Energy Outlook, referred to here as EIA (IEO-00) or EIA 00; and

- the International Energy Agency (IEA), through its biennial World Energy Outlook, referred to here as IEA (WEO-98) or IEA 98. A new World Energy Outlook was due for publication in November 2000.

The three agencies tell similar stories. Despite different dates and methods, they can be regarded as samples of the same vision of what would happen under policies, consumer and citizen demands, and business strategies which continue past trends.2 This ‘conventional vision’ does not assume implementation of the commitments entered into under the Kyoto Protocol, first because the protocol was not ratified at the time the projections were made, and second because we do not yet know either what measures may be taken to implement the protocol or what their effects may be.3 There is likely to be less agreement about these measures and their effects.4 Nevertheless, the trends of the ‘conventional vision’ are the basis for discussions of serious climate change mitigation policies which would alter these trends were they widely adopted.

There are differences among the projections – mainly at the regional and sectoral levels – which can be regarded as sensitivities rather than alternative projections. Each study illustrates variations in economic growth, oil prices and energy intensity. Close comparisons among the studies at a regional or national level are difficult because of differences in definition, while generalizations across countries and regions are also dangerous, since local circumstances affect demand and supply by means other than the international prices or the energy aggregates.

This book approaches the conventional vision from a particular perspective. Our question is whether the energy trends described in the ‘reference’ cases contain such uncertainties, discontinuities and tensions that actions taken to resolve them by governments, private sector companies, and even consumers and citizens collectively may themselves change the energy game. What factors can we see that would alter ‘business as usual’ before we consider the impact of serious climate change mitigation policies? Such alterations would be of immediate interest to those responsible for business, policy and the advocacy of values, whatever the form and severity of future climate change mitigation policies. They are also relevant to the design of such policies in an effective and cheap form, for climate policies designed to change trends may turn out to be unexpectedly costly or even useless if those trends have changed already.

The conventional starting point: energy and GDP

Conventional projections of demand for commercial energy are associated with projections of Gross domestic product (GDP).5 (GDP is not the only useful measure of development, but it is the one generally associated with energy projections.) The conventional procedure, used in all three scenarios under discussion, is to project population growth, growth of GDP per head and energy intensity of GDP. In the conventional vision, world primary energy consumption would grow by about two-thirds between 1995 and 2020, in a world economy which would double in size. Even at the global level, these projections contain uncertainties.

First, some of these projections, made in 1998–2000, may not allow fully for the effect of low growth of the economy and energy consumption in the period 1997–2000. World primary energy consumption actually fell in 1998.6 The average annual growth in global primary energy demand for 1995–2000 is likely to be nearer 1% than the 2% on which the conventional visions are based; and three years’ lost growth of 1% at the beginning, compounded for 20 years, will lower the 2020 figure for global energy consumption by more than 10%.7 The EIA and EC (POLES) cases allow for a 2–3-year interruption in growth in Asia, but then pull back to the trend line. The projected annual increase of consumption by 5,300–6,500 million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe) per year worldwide compares with a recent history of much lower increases: approximately 3,000 mtoe annually over 1973–98.

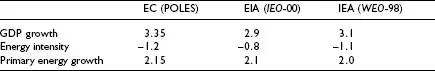

Second, the projections cited already have a range of 1,200 mtoe in their energy projections for 2020. This is more than the current production of Middle East oil. About half of this range can be explained at a global level by slightly different assumptions about trends in economic growth and energy intensity (see Table 2.1). At growth rates of around 3%, a difference of 0.1% in the growth rate of either GDP or energy over 25 years makes a difference of about 5% in the projection for the final year.

Table 2.1: GDP growth and energy intensity comparisons (%)

By rough adjustments, Figure 2.1 shows the effect of adjusting, at the global level, to the ‘round numbers’ of 3% GDP growth and 2% primary energy growth which are broadly consistent with past trends.8 The effect is roughly to halve the range of the forecasts.

Third, all these conventional visions were built from regional or national projections, all project GDP rising more rapidly in developing countries than in industrial countries (and rising very slowly in the emerging market economy of the former Soviet Union). The effect would be that between 1997 and 2020 the developing countries’ share of world GDP would increase by about 10%, with a corresponding fall in the share of the industrialized countries. It is difficult to be certain whether this shift would increase the average energy intensity of the world economy.

Developing countries generally appear to have more energy-intensive economies. In 1996 $1 of Chinese GDP, measured at current US$, required 1,430 g of energy oil equivalent, while $1 of US GDP required only 290 g.9 However, between 1980 and 1996 the energy/$ of GDP ratio fell by 22% in the US; in China the fall was 57%.10 In the Chinese case the improvement appears to have been mainly due to improvements in technical efficiency:...