![]()

Part 1

Commercial and Residential Property

![]()

1

Commercial Property

1.1 Introduction: the fragmentation of ownership

Behind the facade of every commercial building in the UK may lie a complex pattern of relationships created by the unique nature of property as an economic commodity.

The market for property is not necessarily driven by the desire to own land and buildings. It is instead a market for rights in the product which may have many tiers of ownership. Consequently, a single building might represent the property rights or interests of several different parties.

For a given unit of property, there is a basic dichotomy of rights. These are the right of ownership, which may be fragmented, and the right of occupation which (allowing for the existence of time shares and joint tenancies) is usually vested in a single legal person. In fact, the given unit is commonly delineated by its exclusive occupation by an organisation, family or individual. The following example will serve to illustrate the tiers of ownership and the multitudinous interests which can exist in one property.

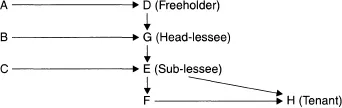

Fifty years ago, A acquired a piece of undeveloped land within the town boundary as a speculation. Ten years later, the land had become ripe for development: it was now profitable to construct a factory unit upon it. A, however, was not a builder and consequently let the land to B on a building lease for 99 years. B constructed a small factory on the site. Thirty-seven years ago B sub-let the completed building to C on a 42-year lease. Ten years afterwards A died and his interest in the property passed to his son, D. Fifteen years ago C assigned his lease to an insurance company, E, who sublet the property to the then occupier, F.

Ten years later E obtained a new 25-year lease from B, who immediately sold out to G. This year F assigned his interest to H, who is the current occupier of the factory.

The current vertical division of rights is illustrated in Figure 1.1. A current contractual relationship exists between four parties whose interests are united in the single property unit. H has the right to exclusive occupation of the factory, while D, G, E and H share in its ownership. D has a freehold interest whose value depends upon the income he can expect to receive from G and his successors in title. G, E, and H have leasehold interests, the values of which depend upon the receipt of a profit rent created by the difference between the rents actually or potentially received and the rent paid to the immediately superior landlord.

Figure 1.1 The vertical division of rights in commercial property

Such a relationship is typical of the manner in which UK property ownership is fragmented. It is especially typical in the case of commercial property (for the purposes of this chapter this includes all office, shop, industrial and institutional property) where the majority of buildings are ‘owned’ by non-occupiers, in contrast to residential property, where the rights of ownership and occupation are fused within the same person in over 50% of the stock of buildings in that sector (see Chapters 2 and 3).

This decomposition of the ownership of commercial property produces the probability of the existence of contractual landlord/tenant relationships, as illustrated in Figure 1.1 where such relationships exist between D and G, G and E, and E and H.

1.2 The valuer’s role

1.2.1 Introduction

As property advisor, the valuer is often employed as an agent on behalf of one of the parties to negotiate an acquisition or disposal of an interest or a variation thereof. The medium for these negotiations is a contract or a lease, which defines the contractual relationship between the parties. Therefore, the valuer needs to have a full understanding of the legal and financial implications of the provisions of the contract or lease in order to advise the vendor or purchaser or landlord or tenant, as the case may be.

There are many factors contained in a lease which directly affect the valuation of interests in land and buildings. For instance, repairing liabilities, lease length, break clauses, user and assignment restrictions and rent review patterns may all, individually or collectively, impact on capital or rental value and must be taken account of by the valuer.

The valuer’s task in such negotiations is to provide a financial interpretation of the terms of the contract.. The investor in property is interested in the return provided by the investment and the valuer is skilled in the quantification of the drivers of that return. His/her advice enables owners and occupiers of property (rights) to make informed decisions concerning the contracts they create and enter into.

We consider below some specific valuation problems which may arise between a landlord and a tenant of a commercial property.

1.2.2 Rental analysis and valuation

Both the landlord and the tenant of commercial property may require advice concerning the rental value of the subject premises in two general sets of circumstances. First, at the beginning of a lease (where new property is to be let for the first time or where a lease runs out and is renewed) the rental value will be assessed primarily by regard to open market rental values based on a standard lease type, and adjusted to take account of the proposed lease terms. Adjustments to the rent and/or the other terms may be made in the negotiation process. Second, at a rent review during the currency of a lease the rental value will be assessed in the light of the extant lease terms, which are not normally changeable.

In either case, evidence derived from recent open market lettings or rent review settlements on comparable properties will be employed and analysed in the estimation of the rental value of the subject property

Example 1.1

10 Station Buildings was recently let on internal repairing terms (IRT) at a rent of £16,000 pa on a 25-year lease with 5-yearly rent reviews. 10 Station Buildings is an office property of 185.8 m2.

Calculate the estimated rental value (ERV) of 12 Station Buildings, a similar property of 167.2 m2 to be let on full repairing and insuring (FRI) terms on a 20-year lease with 5-yearly reviews.

1. Adjust for different repairing liabilities:

The comparable property was let at £16,000 pa IRT. Full rental value on FRI terms would be lower pa by:

External repairing costs (say) | £1,000 |

Insurance costs (say) | £250 |

Total | £1,250 |

Therefore ERV (FRI): | £14,750 |

2. Adjust for different lease length: assume minimal effect (but see p 37).

3. Adjust for different size:

ERV (FRI) | = | £14,750/185.8 m2 |

| = | £79.39/m2 |

£79.39 × 167.2 m2 | = | £13,275 pa |

1.2.3 Capital valuations

The estimation of the capital value of a freehold or leasehold interest in commercial property may be required for loan purposes, for company asset valuation, or upon the purchase or sale of that interest. The estimated rental value of the property will inevitably have to be quantified prior to capitalisation.

Throughout this book it is assumed that the valuation of a leasehold interest should be carried out on a single rate basis (see Baum and Mackmin, 2006, Chapter 7 and Baum and Crosby, 2007, Chapter 7 for a full examination of leasehold valuation methods).

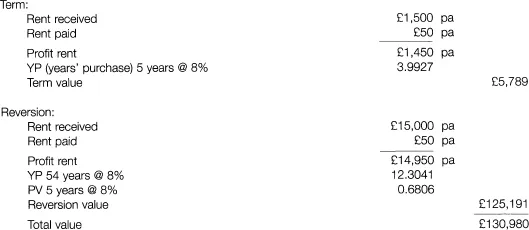

Example 1.2

Referring to Figure 1.1, it appears that G has a leasehold interest, paying a fixed ground rent to D for the remaining 59 years of his lease at a rent of (say) £50 pa. He is currently receiving a rent from E under a lease with five years to run of £1,500 pa. ERV is £15,000 pa All rents are on full repairing and insuring terms. What is this interest worth?

(The valuation approach used is an equivalent yield valuation – see Baum, Mackmin et al, 2006).

It is arguable that the single rate analysis and valuation of leasehold property should be carried out on a net of tax basis, but in this book it is taken for ease that the investor is interested in the gross return and that gross valuations suffice.

1.2.4 Premiums

In rental analysis and capital valuation the payment of a premium, in addition to or in lieu of rent, is a complicating factor which the valuer must take into account.

In the property world the term premium has two distinct applications. The traditional use of the term is to describe a capital sum paid at the start of a lease by a landlord to a tenant in return for a low rent or some other benefit. The payment of this type of premium can produce advantages for both landlord and tenant. To the landlord, the receipt of an immediate cash sum rather than a flow of income is often more attractive for several reasons, including inflation and liquidity preference. In addition, if the tenant is paying a lower rent the landlord’s income stream is likely to be more secure. The tenant, on the other side of the bargain, may prefer to use up capital in return for a reduced rental. Also, rather than holding a lease at a full market rent which might have no disposal value, the tenant will enjoy a profit rent (the difference between the rent he/she actually pays and the full market rent) which might render the leasehold interest valuable in the event that he/she wishes to dispose of it.

It should noted that this situation can apply in reverse where supply exceeds demand, and in such a case the assignor/vendor may be required to pay a premium to a purchaser as an inducement to take over the leasehold interest; such a premium is commonly referred to as a reverse premium. Market conditions will dictate whether a leasehold interest has a positive or negative value, and these conditions will change over a period of time. The pr...