![]()

INTRODUCTION:

A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE BEYOND THE NEW MILLENNIUM?

Each generation has its own rendezvous with the land, for despite our fee titles and claims of ownership, we are all brief tenants on this planet. By choice or by default, we will carve a land legacy for our heirs.

Stewart L. Udall, 1988

Try to imagine in your mind a landscape that has not changed for a thousand years. There is no net movement of animals or plants. Neither the cycle of the seasons, nor death and renewal occurs. Life is stagnant because growth does not occur, biomass does not change. Nothing changes in space or time across this imaginary landscape. Clearly this is not possible, as no landscape remains unchanged. Ecological processes, evolutionary mechanisms and geological forces are continually reshaping landscapes across various scales of time and space, even within what we know of as wilderness. In the history of the biosphere, a millennium is but the twinkling of an eye. Amidst natural change over the last millennium, the effects of human activity have become increasingly felt, and now reach to the outermost atmosphere of planet earth – far more remote to that which we classify as wilderness. Our future, along with the rest of life on earth, depends on landscapes that can support ecological functional processes. To survive beyond the next millennium, human culture depends on the services provided by fully functioning ecological systems. The challenge into and beyond the next millennium is to halt the biosphere degrading effects of human society across several scales of space and time for a more enduring and harmonious relationship with natural processes.

Yet, the earth's resources are diminishing and nature is in retreat. In less than a century, human population and its requirements for space, materials, goods, and amenities have increased by more than five-fold (Ehrlich 1995). Over the past sixty years alone, the explosive growth rates of the global human population and our insatiable consumption of resources have been the cause of widespread collapse of the natural ecosystems. The production of human food and fibre has resulted in the wholesale simplification of many ecosystems and over utilisation of the natural capital resource base. The litany of examples are well-known: the over-harvest of forests, draining of wetlands, spread of agricultural development and high rates of pesticide and fertiliser use, the spread of feral pests, excessive clearing of woodland for domestic stock, urbanisation of foreshores, and the pollution of rivers and estuaries.

Regrettably many species have been lost. Arguably far more serious are the growing signs of functional problems in the operation of many ecological systems (Hobbs 1993, Naeem et al, 1994). Blue-green bacterial blooms in rivers and lakes are symptoms of breakdown of ecosystem processes and function. Even more disturbing because they are unseen by most people, are signs of biosphere dysfunction such as the expanding hole in the ozone layer, global climate change and acid rain (Hempel 1996). Ecosystem function, which individual species alone cannot perform, is of primary importance in sustaining the entire biosphere.

BIOSPHERE ECONOMICS

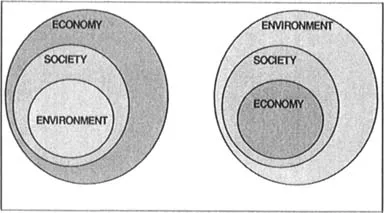

The biosphere is that part of the earth that supports life – providing our living space and our economy. Natural productivity and biodiversity are the warehouses for replenishing and supporting our global society In this way, the human economy is a component of human society, which is in turn part of the biosphere (Figure 1.1). Unfortunately, too often the biosphere is relegated to a small concern of society, which sees itself as a cog in the larger system of modern economy. This economic rationale is the dominant model for decision making in most countries today. It proposes that the biosphere can be looked after best when the economy is functioning well. The opposite model, required for an ecologically sustainable future, suggests that the economy can be looked after best when the biosphere is functioning well.

Modern economies are shaped partly by natural factors that give developed nations an apparent advantage in the economic short-term in various activities – yet arguably a long-term disadvantage. Using economic rationale, policy decisions encourage those activities in an attempt to maintain their competitiveness in the face of market forces. Abundant freshwater would certainly appear to be a natural advantage, necessary for drinking, agriculture, and industry. Yet when governments set water pricing below the real cost of supply for, say, irrigation, taxpayers provide a subsidy for agricultural water use, encouraging overuse and fouling. This happens in Australia, the United States, South Africa and European countries. In contrast, government (or local community) policies based on the model that first considers biosphere functional capacity would promote a sustainable clean water supply over reckless economic rationalism (Figure 1.1). Melbourne, Australia, has one of the cleanest water supplies of any city on the globe today because the visionary forefathers totally protected vast areas of native forest catchment, and buffer areas around catchments for the population and development they could hardly imagine 200 years further on. They put a very high value on long-term, continuing supplies of clean water.

Figure 1.1. Economic rationale (Left) is the dominant model for decision making in most countries. It proposes that the environment can be looked after best when the economy is good. The model required for an ecologically supportable future views the economy as a component of human society, which is in turn part of the ecological systems of the entire biosphere (Right).

Maintaining Ecological Security

The maintenance of ecological processes across large areas of land and sea is crucial to climatic and water cycles, soil production, nutrient storage and pollutant breakdown (see Daily 1997). The diversity of plant and animal species now available to us relies on these ecological processes. We need to keep in mind that, all the world's food and many of our medicines and raw materials are derived from this biological diversity and continuing ecological processes. While we utilise only a tiny proportion of ecological diversity available to us, there is likely to be great scope for as yet unused genetic stock to offer new varieties, or improvements in currently commercialised species. For example, Australia has 15 of the earth's 16 known species of wild soybean and these could be of direct value in the future by providing disease-resistant or other genetically diversified stock.

In addition to physical needs, accessible, untrampled natural environments are also essential to the spiritual well being of humankind. Some sense of harmony with the natural world is a requirement for psychological and spiritual health as well as being a source of immeasurable aesthetic pleasure. Everyone needs the opportunity to enjoy the peace and beauty of nature. Human beings are ecologically interdependent with the natural world, just as other species are with each other.

Public reaction against the loss of biodiversity and loss of productivity from natural systems is growing. The ratification of the Convention on Biological Diversity gives authority and momentum to the campaign to maintain ecological security. Citizens are increasingly concerned with clean air, water and non-toxic food products, as well as protecting a greater proportion of the environment and species assemblages parks and reserves. Many countries are now actively exploring ways to build better reserve networks that comprehensively represent biological diversity and protect natural heritage. However most existing or new reserves will contribute little to sustaining the arguably more important ecological processes and functions at landscape and seascape scales that are fundamental to the health of all life. Even if effectively managed, these protected areas can only ever conserve a very small portion of the world's biodiversity. Yet the erosion of ecological systems and processes continues. Reserves and other protected areas are a necessary, but quite insufficient means alone to maintain biodiversity and ecological processes and functions that humans require for producing food, goods and services as well as other quality-of-life values. We rely on healthy functioning landscape ecosystems for our own health, longevity, security and well being.

No species, no matter how dominant, is independent of all the others. The existence of each depends to some extent on the existence of all. Humanity needs to learn to live within ecological laws that govern the capacity of the biosphere. Ecological law embodies the rules and conditions for nature's services, ecosystem processes and biosphere function across all scales in order to maintain a healthy productive environment. To secure our own future, one of the fundamental goals of society and economics should be to ensure the survival of all forms of life processes within the biosphere (Figure 1.1). Preserving the roles of assemblages of species in ecosystems and their ability to continue to adapt or change (i.e. evolve) through time, is vital to sustaining biodiversity and ecosystem processes (Hansen and di Castri 1992). The diversity of the biosphere has provided the fundamental building blocks for tens of thousands of years of human food, shelter and culture (Wilson 1992). Now, as ever, it underpins ecologically sustainable development for current and future generations.

Those aware of the complexity of biodiversity understand that global interdependence is a necessary part of ecological security. Maintenance of biodiversity in one country depends in part on maintenance of biodiversity in others. That is one reason for the importance of the international Convention on Biodiversity, and the strategies that have emanated from it (eg, Agenda 21, Local Agenda 21). We have a responsibility to each other and our descendants to ensure ecological security now and in the future. The three basic requirements for an ecologically supportable future depend therefore on sustaining ecological integrity, natural capital and biodiversity (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. Three ecological requirements for a sustainable future for the biosphere

| ECOLOGICAL INTEGRITY | The health and resilience of natural life-support systems, including their capacity to assimilate wastes and endure pressures such as climate change and ozone depletion. |

| NATURAL CAPITAL | Sustaining the store of renewable natural resources – eg, productive soil, fresh water, forests, clean air, ocean – that underpin the survival, health and prosperity of human society. |

| BIODIVERSITY | Maintaining the variety of genes, species, populations, habitats and ecosystems. |

Integrating Social Issues

Just as important as the ecological requirements listed above, novel approaches are needed to integrate societal values and the requirements for an ecologically supportable future. The impetus for developing and implementing such a sustainable systems approach on a landscape or regional basis is now coming from many directions, including economic, ecological and social studies (eg, Kim and Weaver 1994, Noss and Cooperrider 1994, Brunckhorst 1995, Brunckhorst and Bridgewater 1995, Gunderson et al. 1995, Steinitz et al. 1996, Costanza and Folke 1997, Berkes and Folke 1998). In essence, these studies have observed failures in current policy and management to produce practical information for decision making and planning that meets social and economic needs while conserving and respecting the limits of biophysical resources (Brunckhorst 1998). Many of these failures relate more to social institutions and management problems than to our lack of knowledge about ecosystems and human effects on them. Such management problems include, for example, too much reliance upon ‘top-down’ approaches, economic determinism, institutional and cross-jurisdictional competition, and poor application of existing information.

Governments attempt to balance the equitable distribution of finite resources across multiple and competing sectoral interests. However, in practice, they do not have all the funds required to implement the variety of programs and on-ground action to meet the challenges of environmental deterioration, biodiversity protection and sustainable resource use. Difficulties in mobilising resources for environmental action are often the consequence of the economic rationale model described earlier. For example, the goal of many modern governments is toward continued economic growth that would seem to undermine moves towards an economically and ecologically sustainable society. An alternative future for an ecologically sustainable society would require social transformations towards a more restorative economy where investment in biodiversity protection and environmental restoration provides, among many benefits, the ‘growth capital’ for future sustainable industries (Hawken 1993, Brunckhorst et al. 1997).

There are signs for optimism however, as the situation in several industrialised countries is very similar to that described by Roger DiSilvestro (1993) for the United States:

Fortunately, survey after survey during the past decade has shown that citizens are willing to pay higher taxes or higher prices for material goods if in return, they receive a cleaner, healthier, ecologically more stable environment. Many politicians have failed to keep up with the times and have stood as obstacles to growing environmental concern. Politicians who remain dreadfully out of touch with the will of their own nation seal their own fate.

Roger DiSilvestro (1993: 243)

Social and institutional transformations are required. If society has expectations that are inconsistent with human connections in the biosphere, then new technology and mounting masses of biological data will be ineffective in halting ecological destruction. The basic challenges have been clear for some time, yet most research has focused too much on classic reductionist studies with little application or transfer to natural resource management dilemmas (Lovejoy 1995, Brussard 1995). There is still too little understanding of the relationship between society and ecosystems at the scale of biocultural landscapes, which I refer to as bioregions. It is not the small-scale self-sufficient communities advocated by some “deep ecologists” (eg, Sale 1985).

BIOREGIONAL PLANNING FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE

Environmental planning and management is a growing field, spending billions of dollars internationally to confront some of the most compelling problems faced by modern society. Until recently these problems were broken up into small parts under the jurisdiction of individual agencies and local governments. The failure of individual sectors to solve large environmental problems has led, in recent years, to an increasing interest in collaborative, multi-disciplinary approaches to landscape scale design, planning and management (see McHaug 1969, Tillman 1985).

Several impediments limit the holistic application of cultural and environmental understanding to integrated environmental planning and natural resource management. These include obstacles to integration not only of a narrow view and application of natural resource management, but also impediments to holistic approaches to watershed or catchment management, wildlife management, community-based programs, lan...