eBook - ePub

The Development of Tropical Lands

Policy Issues in Latin America

Michael Nelson

This is a test

Share book

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Development of Tropical Lands

Policy Issues in Latin America

Michael Nelson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First Published in 2011. Latin America today is similar to Canada in the early 1900s-a sleeping giant, basically underpopulated, whose potential rests on the exploitation of enormous land, forest, mineral, and water reserves. This study, carried out over the period 1967-69, has involved travel throughout much of Latin America north of the Tropic of Capricorn and discussions with people in many different fields, including highway construction, forestry, colonization, and agricultural industries in the forest frontier regions and capital cities of the continent. The collection of data required about twelve months of the author in the field.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Development of Tropical Lands an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Development of Tropical Lands by Michael Nelson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

I

The Role of Tropical Lands in Development in Latin America

In order to place the humid tropical land reserves of Latin America in perspective with regard to their potential role in overall development of the region, it is necessary to have an idea of the productive potential of the resources and of the general development policies in recent decades, the problems in their implementation, and the relative importance they assign to tropical lands. These matters will be taken up in this chapter, as well as the sociopolitical and institutional factors that guide development policy in the agricultural sectors of the tropical countries. In addition the ways in which the agricultural sector affects economic development and employment in these countries will be examined.

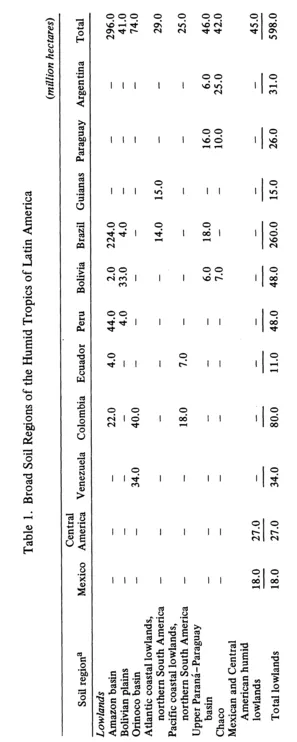

Land Capability for Agriculture

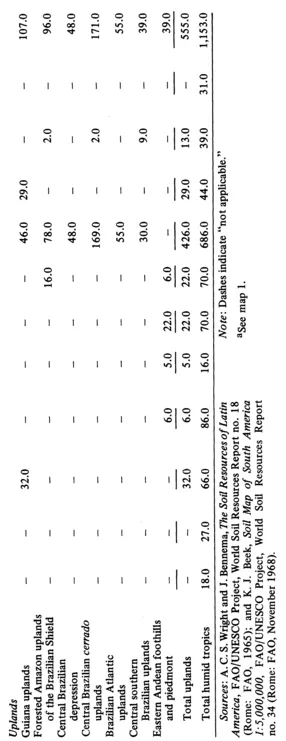

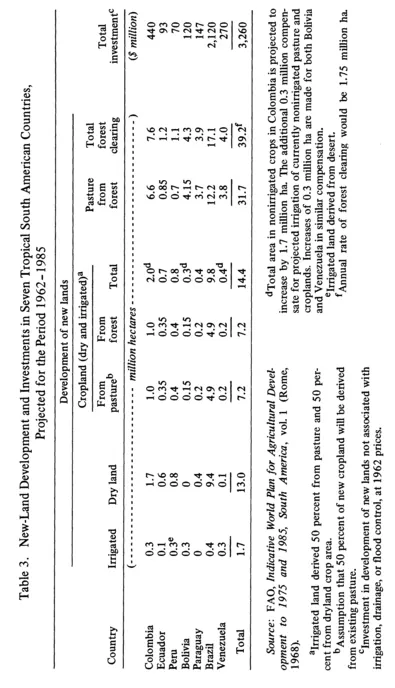

The 12 million square kilometers (km) of the area under consideration—the humid tropical lowlands and uplands and the semiarid Chaco—have been classified into fifteen soil regions, which are shown in map 1 and further described in table 1.1 Soil surveys at various levels of precision have been carried out for about 8 percent of the humid tropics, and exploratory studies have been made for an additional 25 percent. On the basis of this material and miscellaneous observations, the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) has estimated the land capability in the humid tropics of Latin America (see table 2). No data are available on the area that is currently being exploited, nor is there any information on the extent to which the present use is incompatible with the various types of soils.

For six of the principal tropical countries of South America2 it has been estimated that there are about 3.4 million square km of unused arable land (virtually all in the humid tropics), which is five times the exploited area in these countries.3 Indications are that as much as 50 percent of this potential cropland may be in native pasture. Thus if FAO criteria are used to give a global estimate of unused land in the humid tropics of Latin America, it would appear that an additional 3-4 million square km may be available for cultivation and 4-5 million square km for the development of pastures.

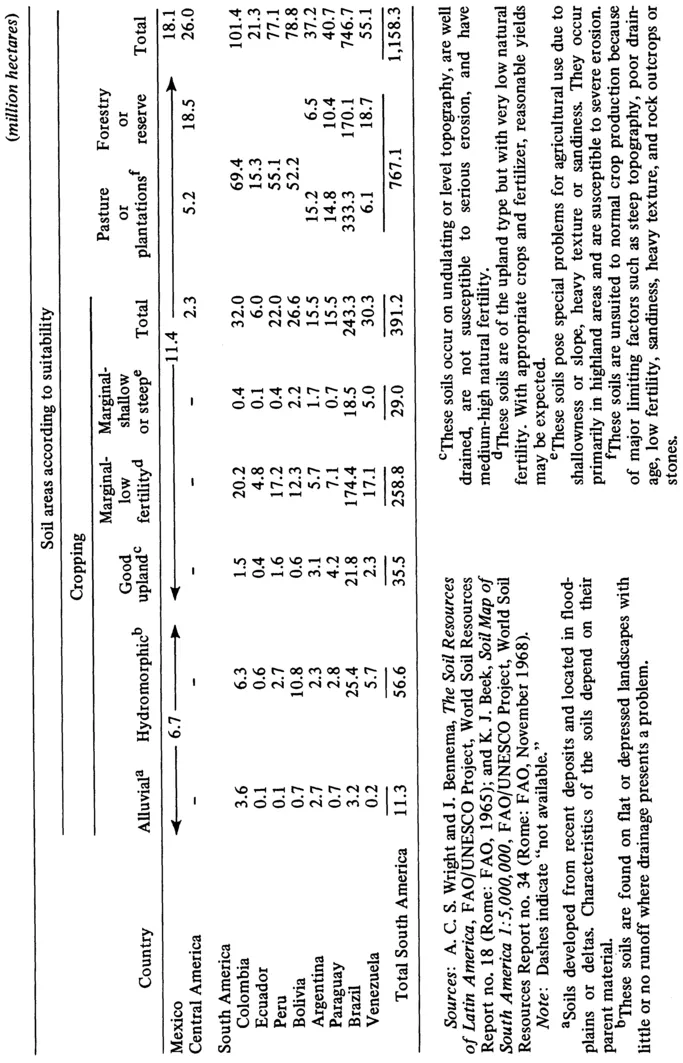

FAO's Indicative World Plan4 represents the first systematic attempt to locate the potential source of the increased agricultural and forest production needed to meet projected demand. Estimates for new-land development during the period 1962-85 for the seven principal tropical countries of South America are shown in table 3. Total investment is projected at $3.26 billion over the twenty-three-year period to clear about 39 million hectares (ha) of forest—32 million ha for pasture and 7 million ha for crops—and to convert 7 million ha of pasture into cropland.5

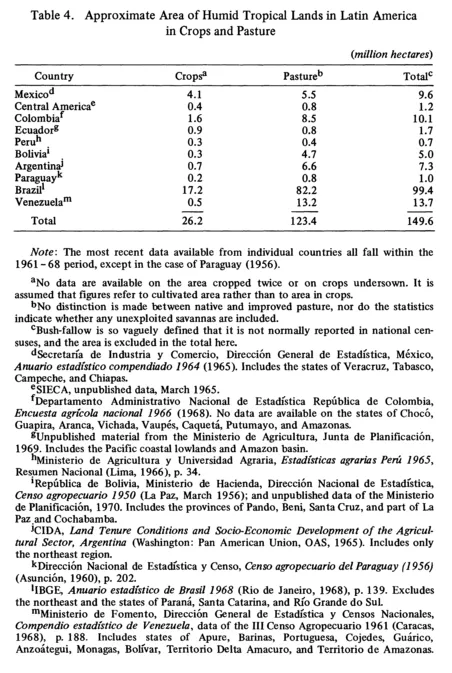

Two conclusions may be drawn from these statistics and projections.6 First, it is probable that only about 2 percent of the vast area covered by the humid tropics is currently being exploited for crops and that 10 percent is in pasture (see table 4), although it appears that as much as 80 percent may be considered suitable for agricultural development. FAO projections call for the exploitation of 6 percent of the estimated arable area and about 30 percent of the pasture potential by 1985. Second, although the relative proportion of land to be developed is small, the absolute areas and the investments involved are enormous. The prospect of clearing jungle at a rate of about 2 million ha per year presents formidable problems in regard to area selection, dispersion in relation to infrastructure, and the fate of forest resources.

Land Capability for Forestry

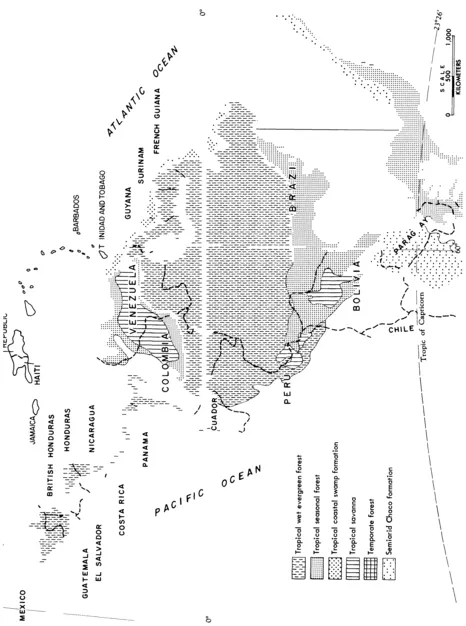

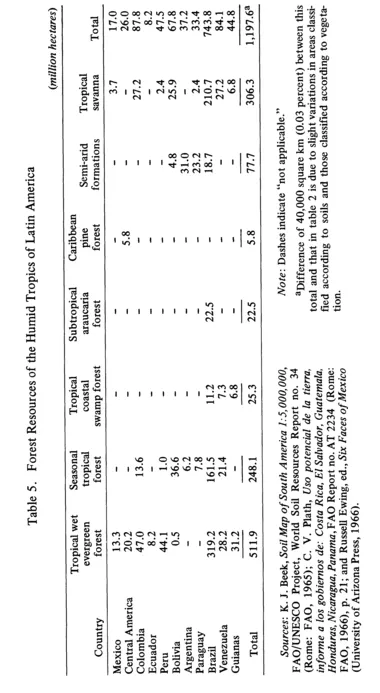

The extent of the forest resources in the humid tropics of Latin America is shown in map 2. About 70 percent of the region is classified as forest—8.5-9 million square km—of which over 95 percent is broadleaved seasonal and equatorial rain forest (see table 5). Since only about 5 percent of this area has

Table 2. Inventory of the Humid Tropical Land Resources of Latin America, by Country

Map 2. Vegetation regions in the humid tropics of Latin America.

been covered by forest inventories, estimates of capability must necessarily be rather general.

Studies of the equatorial forests in Brazil7 indicate that there are more than 700 species, and that on any one hectare there are approximately 1,000 trees over 5 centimeters (cm) in diameter at breast height (DBH), representing about 100 species on the average. The standing volume of all trees over 25 cm DBH is estimated to be in excess of 200 cubic meters per hectare. Of the 1,000 trees per hectare, about 40 would qualify as commercial size (more than 45 cm DBH), with a standing volume of 150 cubic meters;8 10 of these would be species that may be classified as commercially acceptable in current markets, with a standing volume of about 45 cubic meters. Estimates of the commercial volume technically available range between 15 and 60 cubic meters per hectare.9 However, since 60-70 percent of the tropical forest area is inaccessible at the present time and in much of what is accessible products are still subject to laborious and expensive transport to markets over high mountain passes or down tortuous rivers, these figures by no means represent the marketable volume. The forest is considered to be in "balanced climax"; that is, the species composition is stable and annual growth equals annual losses. The annual increment in standing volume is estimated at 3-10 cubic meters per hectare, which, in effect, is the amount available for extraction without depletion of the resource if harvesting is organized to eliminate losses. With the introduction of management programs to change the species composition, the volume may approach 20-25 cubic meters per hectare on a sustained-yield basis.

If the unit figures above are used as general indicators, the standing volume of wood in trees of commercial size would be about 120 billion cubic meters, with an annual increment of about 5 billion cubic meters-about three times the projected world consumption in 1975.10 Assuming a land-clearing rate of 1.75 million ha11 annually over the period 1962-85, the potential volume of wood available from commercial-sized trees would be about 250 million cubic meters per year, over three times the projected level of Latin American consumption (of temperate and tropical woods) in 1975, or the equivalent of total world import demand in that year.12 This calculation in no way is meant to imply that these resources should or could be utilized; it merely indicates the present high level of forest destruction and nonutilization.

Realization of the forestry potential of the region is seriously handicapped by the heterogeneous nature of most tropical forests, the low volume of marketable trees per unit area, technical difficulties in milling or processing a wide range of hardwoods for lumber and particle board, costly processes for pulp and paper manufacture from mixed tropical hardwoods, and the lack of information on the physical properties of many species. The most valuable tropical forests are the pine areas in southern Brazil, southeastern Paraguay, northern Honduras, and northeastern Nicaragua, which account for 1 percent of the total forested area.13 In fact FAO recommends that Brazil, a country with 260 million ha of unexploited equatorial rain forest, should plant 400,000 ha to conifers by 1985.14

Aside from wood and its derivatives, the forest resources can also be used for the conservation of wildlife and for recreation and tourism. In addition the maintenance of forest cover, either undisturbed or through sustained-yield management, could contribute to watershed protection or even to the maintenance of the climatic regime.

Development Policies

Along with most other developing areas, Latin America is generally considered to have had an unsatisfactory record of economic and social progress over the past two or three decades.15 Many reasons are given, including high rates of population growth, low rates of capital formation and economic growth, unemployment, mushrooming urban slums, social inequities, structural deficiencies, civil disorders, political instability, deteriorating terms of trade, a widening gap in productivity and living standards between the region and the developed nations, and the unfavorable consequences of dependency on such nations.

Historically, natural resources have played a preeminent role in development in Latin America, leading to urban and infrastructure investment oriented to international trade and not necessarily adapted to industrialization and mobility of the factors of production within the continent. A further consequence of the natural resource orientation has been a high level of instability in the economy stemming from the volatile commodity prices on the world market and the relative importance of the basic export activities as a source of public revenues.16 In the case of commodities from tropical lands, notoriously unstable markets have ruled for coffee, rubber, sugar, and cocoa.

Since the depression of the 1930s various policies have been formulated to bring about the "take-off." Industrialization was planned with emphasis on import substitution. Then the Alliance for Progress called for massive foreign assistance between 1961 and 1970 to support basic structural reforms in land tenure, taxation, and public administration. Finally regional and subregional integration were designed to achieve factor mobility, specialization, and economies of scale.17

A number of development policies have been proposed over the past ten years that direct attention to the unused tropical land resources. One traditional approach is that summarized by John Karlik, which, in principle, takes the Malthusian thesis as the point of departure. Major emphasis is placed on birth control, agricultural research, and "an integrated transportation system throughout the heart of South America."18 The provision of an adequate diet is seen as an important prerequisite of development.19 The approach is oriented to liberal tariff policies in order to reap the benefits of trade through international specialization and operation of the principle of comparative advantage, while embracing all the reform objectives proposed by the Alliance for Progress.

This policy contains the essential elements of what may be regarded as the "official" prescription put forward by the developed countries of the West. As a result of an analysis undertaken by the Comisión Económica para America Latina (CEPAL) in the 1950s, a major challenge to this thesis came from Raúl Prebisch. In his celebrated article in 196120 Prebisch stated that prevailing trade conditions have a detrimental effect on the economic development of Latin America because of the developed nations' monopoly of both goods and factor markets.21 His position has since been elaborated into a theory of underdevelopment characterized by external dependency.22 This dependency can be technological, economic, political, or cultural. It may manifest itself in a variety of ways—heavy reliance on foreign trade; the concentration of export items or sources of imports; prejudicial trade agreements; the volume and conditions of external debts; foreign ownership of production factors (capital goods and land) and the orientation of such production toward export or domestic markets; the introduction of unsuitable technology; and the structure of the foreign ownership, i.e., si...