- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Atomic Physics

About this book

Using the quantum approach to the subject of atomic physics, this text keeps the mathematics to the minimum needed for a clear and comprehensive understanding of the material. Beginning with an introduction and treatment of atomic structure, the book goes on to deal with quantum mechanics, atomic spectra and the theory of interaction between atoms and radiation. Continuing to more complex atoms and atomic structure in general, the book concludes with a treatment of quantum optics. Appendices deal with Rutherford scattering, calculation of spin-orbit energy, derivation of the Einstein B coefficient, the Pauli Exclusion Principle and the derivation of eigenstates in helium. The book should be of interest to undergraduate physics students at intermediate and advanced level and also to those on materials science and chemistry courses.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Although the Greek philosopher Democritus had postulated the existence of atoms in the first century BC and Dalton’s atomic theory of 1807 laid the basis for modern chemistry, there was no direct evidence for the existence of atoms before the turn of the twentieth century. Indeed, at that time an influential school of German physicists led by Ernst Mach considered the atomic model to be merely a useful picture with no basis in reality.

1.1 THE EXISTENCE OF ATOMS

The situation was dramatically changed by an explosion of experimental investigation over the fifteen years between 1897 and 1912. In the 1870s, technical improvements in the construction of vacuum pumps had made possible the investigation of electrical phenomena in evacuated tubes and the discovery of invisible rays which travelled between an electrically negative electrode (cathode) and an electrically positive electrode (anode) in such a tube.

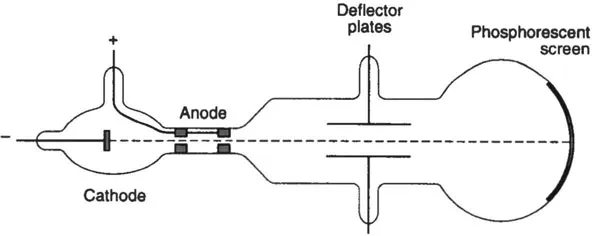

These rays came to be known as cathode rays. At first there was considerable controversy over their nature, but a series of experiments carried out by J.J. Thomson in 1897 demonstrated conclusively that the cathode rays consisted of a stream of negatively charged particles, presumably emitted by atoms in the cathode(Fig. 1.1).

Thomson’s measurements of the deflection of the rays by electric and magnetic fields enabled the speed of the particles to be measured and also the ratio of the charge of a particle to its mass. By the turn of the century, the charge-mass ratio of these particles, which came to be called electrons, could be measured to quite high precision.

However, to give absolute values of the charge and mass, experiments of a different type were required. The most successful were investigations where macroscopic particles such as oil droplets were charged in some way and their motion in electric fields observed. A relatively straightforward measurement of the mass of the oil droplets enabled the charge of the electron to be measured. The famous experiments carried out by Millikan between 1909 and 1916 gave a value for this charge as 1.592 ±.002 × 10 -9 coulomb, less than 1 percent lower than that accepted today. This, combined with Thomson’s results, gave a value for the electron’s mass of approximately 9 × 10 -31kg.

Fig. 1.1 Schematic diagram of J.J. Thomson’s cathode ray tube. Electrons emitted by the cathode arc accelerated through the anode. The beam of electrons hits the phosphorescent screen, producing a luminous spot.

The measurement of electric charge made possible a direct measurement of atomic masses. Back in 1830, Faraday had carried out experiments on electrolysis. He had used his results to suggest that if matter were atomic, then electricity should also be atomic, but the converse is also true. The flow of electric current between two metallic plates in an electrolyte results in a measurable increase in the mass of one electrode. The mass of metal deposited per unit charge flowing can be measured. Assuming that the motion of atoms between electrodes is due to the fact that each atom in the electrolyte carries a specified number of excess electrons, the mass of a single atom can be calculated.

The investigation of cathode ray tubes produced another important line of experimentation. In 1895 Röntgen had discovered that cathode rays impinging on glass or metal produced a new type of ray - the X-ray. These rays were shown to have wave-like properties and in 1899 their wavelength was estimated by the Dutch physicists Haga and Wind to be of the order of 10-10m, using diffraction at a v-shaped slit. In 1906 Marx demonstrated that the speed of the waves was equal to that of light to within experimental error, and it became generally accepted that X-rays were electromagnetic radiation like light but with much shorter wavelengths.

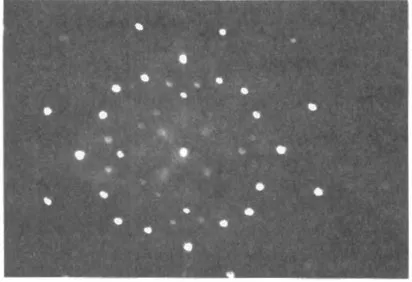

In 1912 Laue in Germany and Bragg in England demonstrated the diffraction of X-rays by the regular pattern of atoms in a crystal lattice. These diffraction patterns gave the first direct evidence of the existence of atoms and of their sizes An example is shown in Fig. 1.2.

Fig. 1.2 Laue diffraction pattern caused by the diffraction of X-rays by the regular lattice of atoms in rock salt.

In 1897. Rutherford had found that pieces of the naturally occurring element uranium emitted two types of ray which were termed α rays and β rays. Both could be deflected by electric and magnetic fields and were therefore presumed to consist of charged particles. The β particles were found to have the same charge and mass as cathode ray electrons, so were assumed to be electrons. The α rays, on the other hand, were considerably more massive. Measurements of their charge and mass suggested that they consisted of helium atoms from which two electrons had been removed. This was confirmed by Rutherford and Royds in 1909, who fired a rays into a sealed and evacuated vessel and showed that helium accumulated in it. The evidence was conclusive that an α particle consisted of a helium atom from which two electrons had been removed.

This experiment also confirmed suggestions about the physical meaning of the atomic number Z. This number had been introduced to define the order of elements in the periodic table. Hydrogen had Z =1, helium Z =2 and so on. The identification of α particles with helium atoms suggested that Z defined the number of electrons in a particular atom.

By 1912, therefore, direct evidence existed on the mass of individual atoms and the size of these atoms. Even more interestingly, the electron appeared to be a constituent part of the atom, suggesting some internal structure.

1.2 THE SIZE OF ATOMS

Turning from the historical development of the subject, it is worthwhile to sum up the measurement of atomic masses and dimensions.

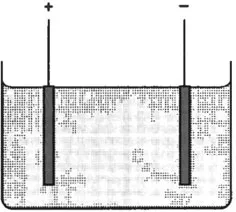

As mentioned above, direct measurement of atomic masses can be made using electrolysis. A typical electrolysis cell might consist of two copper electrodes immersed in a bath of copper sulphate (Fig. 1.3). A potential difference between the electrodes causes a current to flow and the deposition of copper on the cathode.

Fig. 1.3 Electrolytic cell. The anode and cathode are immersed in an electrolyte such as copper sulphate solution. Positively charged copper ions are attracted to the cathode and are deposited there.

Several assumptions have to be made. First, it is assumed that in solution the copper sulphate crystals split up, giving free atoms of copper and that these free atoms have an excess positive charge. Second, using chemical knowledge that copper is divalent, it is assumed that the copper atom has lost two electrons. This is a reasonable extrapolation from chemical valence theory, if it is assumed that chemical bonds result from the exchange of electrons, and that the lightest atom, hydrogen, has only a single electron to exchange. A copper atom in this state is referred to as being doubly ionized, Cu++. A final assumption is that all copper ions attracted to the cathode stick to it and gain further electrons to become electrically neutral again. The experiment then consists of driving a known quantity of electricity through the cell and measuring the increase in mass of the cathode.

Experiments can be carried out with different elements and results confirm the atomic theory and the theory of valence. Most interesting for our discussion is the calculation of the mass of an atom of hydrogen, the lightest element. This turns out to be 1.67 × 10 -27 kg, approximately 1800 times that of an electron.

Knowing atomic masses, and the density of materials, it is straightforward to obtain values for atomic dimensions. The only problem is that unless the atoms in a sample of material are arranged in a regular pattern, the answer is not very meaningful. For crystalline substances. X-ray diffraction enables the arrangement of atoms to be discovered. The dimensions of the crystal structure can then be calculated.

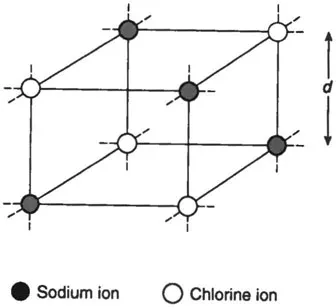

For example, crystals of rock salt (sodium chloride. NaCl) are found to have a cubic structure, with sodium and chlorine ions on alternate corners (Fig. 1.4). If M is the kilogram molecular weight of NaCl and ρ the density of the crystal, the volume of one kg-molecule is

Fig. 1.4 A single cell of the simple cubic lattice of sodium chloride.The lattice is held together by the attraction between the positively charged sodium ion and the negatively charged chlorine ion.

There are 2N atoms in one kg-molecule, where N is Avogadro’s number. Therefore the distance between the centres of atoms, d is given by:

For sodium chloride, this works out as 2.8 × 10-10m and similar results are obtained for other crystals

Of course, such calculations only tell us the distance between the centres of the atoms and hence the maximum possible size for an atom. To go further, it is necessary to investigate the structure of the atom itself.

2

The structure of the atom

Any attempt to construct a model of the atom must start from two experimental facts. First, the atom is electrically neutral. Second, it appears to contain electrons which are negatively charged and relatively light in mass compared with the atom itself (the word ‘appears’ must be included, because the fact that an electron is emitted by an atom does not necessarily mean that it exists in its free-space form inside the atom).

2.1 FIRST MODELS - THE THOMSON ATOM

The first detailed model for atomic structure was devised by J.J. Thomson in 1904. Knowing the charge and mass of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Main symbols used in text

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The structure of the atom

- 3 The quantum mechanical picture of the atom

- 4 Atomic spectra

- 5 Fine structure of spectral lines and electron spin

- 6 The interaction of atoms and radiation

- 7 More complex atoms

- 8 The helium atom and term symbols for complex atoms

- 9 Further discussion of atomic structure

- 10 The atomic physics of lasers

- 11 Atoms in external fields

- 12 Single atom experiments

- Appendix A Rutherford’s scattering formula

- Appendix B Angular momentum operators

- Appendix C Time-independent perturbation theory

- Appendix D Time-dependent perturbation theory - the calculation of the Einstein B coefficient

- Appendix E Quantization of the electromagnetic field

- Appendix F The Pauli exclusion principle

- Appendix G Eigenstates in helium

- Appendix H Exercises

- Appendix I Further reading

- Appendix J Useful constants

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Atomic Physics by D.C.G Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Nuclear Physics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.