eBook - ePub

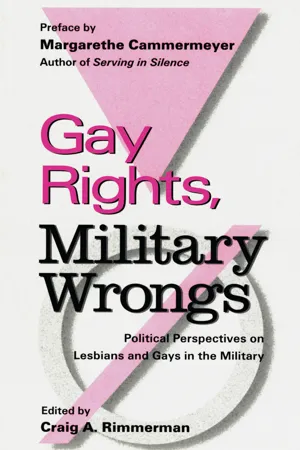

Gay Rights, Military Wrongs

Political Perspectives on Lesbians and Gays in the Military

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gay Rights, Military Wrongs

Political Perspectives on Lesbians and Gays in the Military

About this book

First Published in 1996. From 1980 to 1990 nearly 17,000 service members were discharged from the military because of their homosexuality. This book places the debate of homosexual military service in its historical, theoretical, and political context. Timely and compelling, with all the court options in the highly published cases of Col. Margarethe Cammermeyer, Gay Rights, Military Wrongs, reports on the state of prejudice and discrimination facing today's homosexual military personnel and their prospects for future equality.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Policy Context

Chapter 1

Race-ing and Gendering the Military Closet

The U.S. military’s lesbian/gay exclusion policy is built on intersecting ideas about sexuality, race, and gender.1 The exclusion policy embodies a particular array of race and gender relations and encourages violence against sexual minorities—and, by extension, against any group constructed as “Other” or “undesirable.” It provides sexual harassers with a tool for sexual extortion, and it has been applied disproportionately against women in the U.S. armed forces.

In its newest incarnation as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue,” the military lesbian/gay exclusion policy institutionalizes rather than eliminates the military closet. Lesbians and gay men in the military are asked to remain silent and invisible, to hide their “othered” identities, so that the military can bolster its androcentric, heterocentric image. Their ability to remain closeted is constrained by the predominant society’s ideas about sexual behavior of people of color and of people gendered “masculine” and “feminine.” That is, the military closet comes in “White” and “Colored,” “His” and “Hers” versions, and the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy is used to police the race and gender lines in the U.S. armed forces. This chapter explores the construction of the military closet through an examination of: 1) the context of the policy debate; 2) the comparative studies used to inform that debate, including the personnel practices of other state militaries and the past integration experiences of the U.S. military; and 3) the raced and gendered conceptualization of human sexuality prevalent in contemporary U.S. society.

Fundamentally, the debate over lesbians and gay men in the military is about the politics of identity and practices of inclusion/exclusion. Who am I? Who are “we”? Gender identity, racial/ethnic identity, sexual identity, and civilian/military identity are dimensions of these questions. Conflicts emerge in the intersection of our multiple identities and the politics of drawing boundaries between “us” and “them.” State institutions, such as the legislature, the courts, and the military, officially draw and redraw these boundaries through acts of law, case decisions, and personnel policies. These (re)drawings are political; that is, they are based on the power of the state to determine who belongs and the price of belonging, as well as to coerce or punish, or to issue benefits—that is, to dictate “who gets what, when, and how” in terms of the distribution of resources in a society.2

In 1992, the U.S. military’s personnel policy regarding sexuality came under intense public scrutiny, and efforts were made to draw lessons from the practices and policies of other state militaries and from analogous experiences in U.S. society. In its search for such lessons, the U.S. government commissioned analyses by the RAND corporation and the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO). These studies are important because they were intended for use as scholarly and nonpartisan justification for either mamtaining or ending the U.S. military’s lesbian/gay exclusion policy. Although they provided important information for the policy debate, the RAND and GA studies neglected the raced and gendered construction of the U.S. mihtary lesbian/gay exclusion policy.

Students of comparative politics know that we must be very careful about what we seek to compare. We must identify the assumptions underlying our comparisons and the models we measure against, and we must acknowledge the distortions across cultures, communities, and time created by the degree of abstraction necessary to make generalized comparisons. In examining the RAND and GAO analyses, I began to wonder about the politics of comparative analysis of research on mihtary personnel policies. Where ought the United States look for lessons on this issue?

The experiences of foreign state militaries which have ended policies of exclusion (such as Canada, Australia, Israel, and the Netherlands) show that policy change is possible, that the circumstances under which such change occurs vary, and that inclusion policies and their implementation differ widely. The U.S. military’s own history of ending racial segregation and opening to include women in first auxiliary and then regular military service illustrates both resistance to change in mihtary culture/identity and the possibility for such change. The U.S. domestic analogies of ending sexuality-based exclusion policies among fire and police personnel show that this is not a case of the mihtary going first in changing social attitudes and behaviors in the United States.3

The U.S. Policy Debate

On the campaign trail and in his campaign text, Putting People First, U.S. presidential candidate Bill Clinton outlined his plan to create a more democratic and representative government. Among other things, he pledged to end the exclusion of lesbians and gay men from military service.4 On 29 January 1993, President Clinton began action to fulfill this pledge. He sent a memorandum to the Secretary of Defense telling him to draft an executive order “to end discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in determining who may serve in the Armed Forces.”5 The announcement met with tremendous opposition from the mihtary as well as much of the Congress and the general public, and the issue dominated the media, cutting Clinton’s post-inauguration “honeymoon” short.

For the next six months, members of the administration met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and congressional representatives, trying to design a policy that would keep Clinton’s promise without alienating key military and political leaders. During this time, the lesbian/gay exclusion policy was “suspended”: recruiters were not supposed to ask about sexuality or sexual identity, and pending discharge proceedings were postponed, leaving many service personnel in a quandary—they were unable to resign and leave the service if charges were pending, yet they were being passed over for promotion and could not be deployed with their units outside the continental United States. Meanwhile, investigations of suspected lesbian/gay personnel by the Army Criminal Investigative Command (CIC), the Naval Investigative Service (NIS), and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (OSI) continued, targeting people who had made public statements about their sexuality.6

Finally, on 19 July 1993, Clinton announced the new “compromise” policy Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue, which would allow lesbians and gay men to serve so long as they did so quietly and discreetly—rather than “openly and avowedly,” as supporters of a continued ban phrased it—and did not engage in any prohibited conduct. After much debate and revision, Congress incorporated the new policy into the Defense Authorization Act of 1994, which Clinton signed on 30 November 1993.7 The Act took effect at the beginning of the fiscal year; in the interim, preliminary regulations were issued by the Department of Defense on 22 December 1993, with the finalized rules coming into effect on 28 February 1994.8 In March 1995, a federal court held the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy unconstitutional; the Justice Department announced that it would appeal the case.9 House Speaker Newt Gingrich (RGA), who had earlier called for the new Republican majority in Congress to reinstate the lesbian/gay exclusion rule, appeared to drop the issue.10

The lesbian/gay exclusion policy has a long history in the U.S. military. Soldiers in the Continental Army were “drummed out of the service” for engaging in same-sex relations, according to researcher Randy Shilts, and during the 1860s, could be rejected from enlistment or removed from the ranks for “(h)abitual or confirmed intemperance, or solitary vice,” according to the Manual of Instruction for Military Surgeons.11 The first explicit policy to sanction “assault with intent to commit sodomy” was codified in the Articles of War of 1916, which took effect 1 March 1917. The behavior or conduct of the soldiers, not their sexual identity per se, was the grounds for court-martial and, usually, imprisonment and subsequent dishonorable discharge. At the end of World War I, Article 93 of the Articles of War (4 June 1920) established consensual sodomy as a dischargeable offense. Efforts to purge gay men from the ranks included the Navy’s infamous “gay dragnet” at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1919-20.12

In 1942, the regulations were revised to reflect the then-current interpretation of homosexuality as a psychological illness rather than a criminal offense.13 Recruits or draftees with “homosexual tendencies” were deemed unsuitable for service and were not enlisted or were discharged if already in service, unless they were considered “treatable,” in which case they underwent “rehabilitation” and were retained for service. The language of the 1942-43 regulations blurred the distinction between identity and conduct and allowed greater command discretion to determine whether soldiers identified as gay would be retained or discharged. Some gay soldiers were given honorable discharges; many were given general or “bad conduct” discharges.14

At the end of World War II, the diverse policies of the different services were replaced by the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). Article 125 of the UCMJ prohibits sodomy, defined as anal or oral penetration, whether consensual or coerced and whether same-sex or opposite-sex, and does not exempt married couples. Under Article 125, the maximum penalty for sodomy with a consenting adult is five years at hard labor, forfeiture of pay and allowances, and dishonorable discharge. Article 134 of the UCMJ, also known as the “General Article,” sanctions assault with the intent to commit sodomy, indecent assault, and indecent acts, and prohibits all conduct “to the prejudice of good order and discipline in the armed forces.”15 The maximum penalty is the same for each of these offenses as for sodomy, except in the case of assault with intent, which has a maximum of ten rather than five years confinement.

On 16 January 1981, W. Graham Claytor Jr., a Carter appointee in the Departmen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: The Policy Context

- Part II: Policy Analysis

- Part III: Policy Implications

- Selected Bibliography

- Appendix A. Margarethe Cammermeyer v. Les Aspin

- Appendix B. Margarethe Cammermeyer v. William J. Perry

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Gay Rights, Military Wrongs by Craig A. Rimmerman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.