![]()

Part 1

Introducing the farmer innovation approach and some remarkable innovators

![]()

1

Entering research and development in land husbandry through farmer innovation

Chris Reij and Ann Waters-Bayer*

Since 1997, the second phase of the action-research programme Indigenous Soil and Water Conservation (ISWC 2) has been operating in seven countries in anglophone and francophone Africa, while its sister programme, Promoting Farmer Innovation in Rainfed Agriculture (PFI), has been operating in East Africa. Both have taken a similar approach to agricultural research and development through building on local innovation and encouraging farmer experimentation and Participatory Technology Development (PTD). This chapter outlines the main components of this farmer innovation approach.

BACKGROUND

Despite much rhetoric about the need for more demand-driven and participatory approaches to agricultural research and development, the transfer-of-technology (ToT) model continues to dominate in most countries in Africa (Bauer et al, 1998). This model implies that scientists generate new or improved technologies which are then transferred by extension agents to farmers. However, many of the technologies generated and promoted in this way are too expensive for the hundreds of millions of small-scale farmers who cannot afford to invest in the packages of required inputs, such as introduced seed, fertilizers and pesticides. Moreover, these packages are often standardized and promoted countrywide, without regard to agroecological differences, and poorly suited to the diverse and variable conditions of smallholders in semi-arid and other marginal areas (eg Howard et al, 1998). Many of these farmers have therefore been reluctant to adopt the technologies offered by conventional research and extension, despite sometimes massive ‘encouragement’ for them to do so.

For years, the World Bank strongly pushed a form of ToT called Training and Visit (T&V). This was meant to have an inbuilt feedback loop: through the extension agents, farmers could convey their assessment of the technologies back to the scientists. In actuality, however, this feedback rarely took place (Bauer et al, 1998). Reflections on the T&V system by the World Bank and the various countries involved led to suggestions to strengthen the voice of the farmer (Technical Centre for Agricultural Rural Cooperation (CTA), 1996). The dissatisfaction with conventional extension triggered the development of new approaches, such as Farmer Field Schools (Röling and van de Fliert, 1994). Some international and national research institutes have started to explore more participatory ways of working, such as through greater use of on-farm trials and more involvement of farmers in problem analysis and evaluation of trial results. The focus has been primarily on farmers’ testing of technologies generated by scientists. Basically it concerns applying participatory approaches to improving ToT, but gives little or no attention to technologies generated by farmers or to strengthening farmers’ capacities to develop and adapt technologies.

With growing population pressure and growing awareness of environmental degradation, farmers are seeking more productive ways to use the available resources without depleting them. They have to adjust rapidly to changing conditions. If agriculture is to be sustainable, farmers must be capable of actively and continuously creating new local knowledge (Röling and Brouwers, 1999).

For some time, publications by discerning development professionals have reported on farmers’ own experimentation and innovation (eg Johnson, 1972). In the 1980s, books by Robert Chambers and his colleagues (1983, 1989) and Paul Richards (1985, 1986) drew wider attention to this. Roland Bunch (1985) argued, on the basis of the experience of the non-governmental organization (NGO) World Neighbors that worked with peasant farmers in Central America, that strengthening their capacities to experiment and solve their own problems was the key to sustainable agriculture. This call was taken up by various other NGOs, especially the Information Centre for Low-External-Input and Sustainable Agriculture (ILEIA) (eg Reijntjes and Hiemstra, 1989, Haverkort et al, 1991). Rhoades and Bebbington (1995) refer to a large number of experiences in supporting farmer experimentation and building on local initiatives to solve problems. However, these experiences remained marginal to mainstream research and development programmes which continued with the ToT approach. Both ISWC 2 and PFI decided to make a concerted effort to build on the potentials of farmer innovators and their innovations in Africa, with the ultimate aim of institutionalizing the promotion of farmer innovation and PTD (see Box 1.1) within national agricultural research and extension systems.

BOX 1.1 PARTICIPATORY TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT IN LAND HUSBANDRY

Participatory Technology Development (PTD) refers to collaboration between farmers, development agents and scientists in a manner that combines their knowledge and skills. The heart of PTD is farmer-led experimentation to find better ways of using available resources to improve the well-being of families and communities. The purpose of supporting farmer experimentation is to strengthen farmers’ capacities to seek and try out new ideas so that they are better able to experiment and to adjust to changing conditions. The purpose is not to convince farmers to adopt a new technology, but rather to encourage them to test new possibilities and choose what is right for their circumstances or adapt the new ideas to their conditions.

A close look at the many good examples of this kind of interaction between farmers and ‘outsiders’ reveals a common pattern, which consists of six main clusters of activity (van Veldhuizen et al, 1997):

• Getting started: establishing contact between farmers and ‘outsiders’ and agreeing to take this approach to improved land husbandry.

• Analysing the situation: farmers and ‘outsiders’ seek a joint understanding of local problems, resources and opportunities, often using tools of Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA).1

• Looking for things to try: joint identification of possible solutions or new opportunities for improving land husbandry and agreeing on what to try out first.

• Trying things out: experimenting with and adapting the new idea(s) in trials planned and implemented by farmers, with the support of development agents and scientists, and monitored and evaluated jointly according to agreed criteria.

• Sharing the results: letting other farmers, development agents and scientists know what came out of the experiments and how they were done.

• Sustaining the process: helping farmers to organize themselves to continue this kind of interaction and to obtain new ideas and inputs with which to experiment, and creating a political and institutional environment that fosters PTD.

Farmers’ innovations show how local resources can be used to address problems and opportunities that farmers have recognized by doing their own informal situation analysis. The options that farmers involved in PTD may consider for testing include:

• local farmers’ innovations in order to validate them or test them more widely;

• other ideas developed by farmers in other areas to address the same problem or opportunity;

• ideas from formal research and extension to address the same problem or opportunity.

Thus, identifying farmer innovations can be a door to PTD at the point of ‘Looking for things to try’.

INTRODUCING THE FARMER INNOVATION PROGRAMMES

Indigenous Soil and Water Conservation in Africa

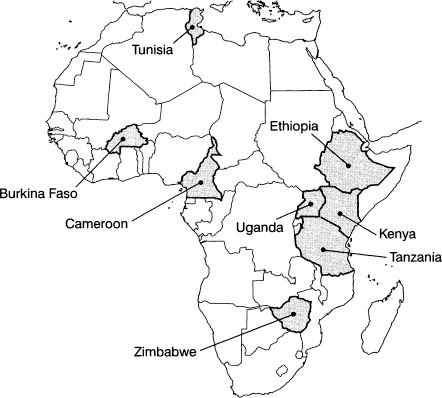

The first phase of the ISWC research programme focused on analysing the dynamics of indigenous soil and water conservation (SWC) practices in Africa. Twenty-seven case studies from 15 countries showed that many indigenous practices are being maintained and expanded by farmers, in contrast with many modern SWC techniques promoted by development projects (Reij et al, 1996). The second phase (ISWC 2), which operates in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda and Zimbabwe (see map on page 7), aims to improve the effectiveness of both indigenous and modern SWC practices through a process of joint experimentation involving farmers, scientists and development agents. It promotes research on local practices and innovations in SWC, assists in disseminating the results, and supports lobbying platforms to show policy-makers that building on ISWC practices is a promising path to development.

An unknown number of farmers are experimenting with SWC techniques on their own initiative. ISWC 2 pays special attention to these innovators who are often overlooked as a source of inspiration for development. Identification of farmer innovators who are already in the midst of informal experiments is an entry point into a process of PTD. The ISWC 2 approach involves training scientists and extensionists in PRA and PTD, identifying farmer innovators and their innovations, networking between farmer innovators, participatory research to develop and validate improved techniques and systems of land husbandry, and disseminating ideas and methods through farmer-to-farmer exchange.

In each collaborating country, a ‘lead agency’ concerned with agricultural research or development maintains links with other local research, development and teaching institutions interested and/or experienced in participatory approaches to improving land husbandry. A coordinator attached to the lead agency manages the programme activities. A steering committee, composed mainly of representatives from the collaborating organizations, plans and evaluates activities funded by the programme. All seven ISWC teams learn from each other during annual review meetings hosted by different partner countries in Africa.2

The ISWC 2 programme defined farmer innovators as those farmers who spontaneously try out new things, without the direct support of formal research and extension. They are not the ‘model’ or ‘progressive’ farmers who have often been selected by projects to test new crop varieties or packages of external inputs. The programme regards the farmers and their innovations, not the scientists and their technologies, as the starting point for development. This does not deny the important role that scientists can play. ISWC 2 seeks to link scientists, extensionists and farmer innovators in joint efforts to improve local and introduced practices of managing land and water.

Map 1.1 African partner countries in the ISWC 2 and PFI programmes

Promoting Farmer Innovation in Rainfed Agriculture

The PFI programme was developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Office to Combat Desertification and Drought (UNSO) in the context of implementing the Convention to Combat Desertification (CCD). It operates in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania and is, like ISWC 2, funded by the Directorate General for International Cooperation (DGIS). The goal is to harness the energies, ideas and rich experiences of innovative farmers for improving rainfed agriculture. Innovations in SWC are identified and disseminated.

Methodology development

A methodological approach to promoting farmer innovation was developed and refined during the course of PFI and ISWC 2. Here, we explain the major components of this approach and illustrate them with examples from experiences in the various countries, making cross-references to the relevant chapters in this book.

This presentation of ten components does not mean that these were or should be neatly implemented one after the other. In practice, several components run parallel to each other or are repeated several times during the process. Nor does it mean that each country involved in ISWC 2 and PFI has given the same attention to each component. The vastly differing socioeconomic and agroecological conditions in each country have led to different emphases being placed.

The three country programmes under PFI followed a series of ten steps (see Figure 17.1) fairly closely, whereas each of the seven countries under ISWC 2 designed its programme in the light of its own perceptions, experience and history, as well as the capacity and orientation of the partner organizations.

Within each country, the ISWC 2 and PFI programmes concentrated their initial work in selected regions – for example, the Southern Highlands in Tanzania, parts of the Central Plateau of Burkina Faso, the Tigray region in northern Ethiopia, the Kabale district in south-west Uganda. An exception was the Zimbabwe programme: it had already considerable experience in participatory research and extension in Masvingo province before ...