- 116 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Progression in Primary Design and Technology

About this book

First Published in 1999. Progression in Primary Design and Technology is a book that places the issue of progression firmly into the classroom situation. It encourages the reader to explore practice and to develop a new perspective on progression for individual children. It is recognised that teachers have an extremely demanding role in which normative expectations and standards guide practice. Some children do not make expected progress for a variety of reasons. The main purpose of this book is to provide activities through which teachers and trainees explore the issues and work towards classroom provision that is both challenging and flexible for all children.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Progression in Primary Design and Technology by Christine Bold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Introduction

Before reading this chapter, it will be useful for the reader to note their own definition of the term progression in relation to teaching and learning in design and technology. This will help to focus the mind and to explore whether the reader’s understanding of it is the same as that of other people. This is not to suggest that there is a single meaning, but that there might be several ways of viewing the term progression and the way it is used.

As a classroom teacher and in my work with trainees on Initial Teacher Training (ITT), I have experienced working on a variety of activities that have focused my attention on the progressive development of capability in design and technology. A teacher’s first priority is to ensure that children make progress. First explorations into what progression meant for individuals in my classes were through case studies and small classroom-based research projects in science, mathematics and literacy. When government initiatives established design and technology in the primary school curriculum, it was natural for me to turn my attention to the complex issue of progression inherent within the subject. The first challenge for the teacher is how to identify children’s individual levels of development in different aspects of design and technology. The second challenge is to decide what classroom provision to make that enables progression to occur.

A good starting point in considering progression is to reflect on some aspects of the relationship of design and technology with other subjects in the school curriculum. Design and technology has developed as a primary school subject to the point where it is now part of every child’s entitlement in a broad and balanced curriculum. It has strong links with science, in both content and process, particularly in the testing and use of materials and products. For primary school children technology also has strong links with mathematical and language development. A design-and-make task is a highly motivating and relevant context for children to learn about shape, space and measures – there is no better way to teach about different levels of accuracy in measurement for different purposes. Such tasks require a variety of modes of communication and may provide opportunities for children to write in a range of different genres. Engaging children in design-and-make activities encourages less confident writers to write up their findings and ideas. As part of the process, they recognise the need to be able to tell others about their project and to enable other children to learn from their experiences.

It is also important that children understand the relevance of historical developments that exemplify the technological process. The history of everyday technological products fascinates children. Looking at technological change conveys the essence of the design and technology process, and helps children to learn the meaning of ‘meeting needs’ and ‘fitness for purpose’. Study of the historical development of the bicycle with children, trainees and teachers is an effective way of exemplifying the technological process.

There are also strong links with art, craft, Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and cross-curricular themes such as the environment. Each curriculum area has its own progression that should ideally be taken into account when planning design and technology activity and I shall endeavour to highlight some aspects within the text. However, the focus is the subject of design and technology; in order for it to maintain its own identity it is useful not to assume links with science. Scientific links in particular will receive little mention.

On entry to ITT, trainees may have a high level of skill in some aspects of the subject, perhaps having experienced technology at GCSE level, but often in one specific strand such as food technology or graphic design. Trainees often have a limited understanding of the whole process, as their own education seemed to focus on products. My experience in ITT includes the development of courses for trainees across the whole primary age range. This increased my interest in the strands of progression that emerged and became evident while teaching trainees how to recognise children’s individual strengths and weaknesses. The aim was for trainees to recognise opportunities for developing children’s capability in the subject, as this is an area of difficulty across the curriculum. Several years of teaching experience are often necessary for the skill of formative assessment at an individual level to become secure.

At school level, many teachers now have several years’ experience in teaching design and technology. They have a sound understanding of the process skills and have developed expertise in the use of tools and a variety of materials. Despite this experience, there is concern about teachers’ lack of subject knowledge and the Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED 1998) claim this is the main reason for pupils’ lack of progress. In a recent attempt to improve standards of teaching in the subject, the Teacher Training Agency (TTA 1998a, b) have published texts to help teachers assess and improve their own knowledge. However, lack of subject knowledge among teachers is not the only issue that affects the standards of teaching and pupil performance in the subject. The greatest barrier to progress in the subject may be lack of suitable accommodation and resources to create appropriate activities and products. This has been recognised by OFSTED (1996).

Where they are available, classroom assistants often spend time with children completing practical design-and-make tasks, and therefore have a sound knowledge of the use of tools and the processes involved. They also have the opportunity to take courses designed to enhance their understanding of how children learn the core subjects and to provide them with professional qualifications. For all the above reasons, ITT and in-service courses need no longer focus on skill development alone. Courses designed to focus on the nature of progression and on how to help children develop capability in design and technology will benefit all concerned. Through such an approach, the skill development takes place within a contextual setting that encourages and stimulates deeper reflection on the deeper issues involved in progression.

OFSTED (1998) recognised significant improvements in the teaching and learning of design and technology but comment that the teachers’ expectations were too low. Inspections identified that many teachers still did not use assessments to inform future planning and were unclear about differentiated work. This suggests a significant need for training teachers to focus on progression at a variety of levels. To understand what progression might mean for the individual child it is necessary to focus on the progression that actually exists within the subject itself. Looking at Key Stages is too broad an approach that fails to reveal adequately the progression that is so important. Much of the focus in current literature (e.g. National Association of Advisers and Inspectors in Design and Technology (NAAIDT) 1998) is on what children should be able to do at the end of a Key Stage, but provides few practical clues about how to reach the desired outcome. Consequently, children may not make the progress of which they are capable by identifying smaller steps of learning to use flexibly within the classroom. It is essential that progressive levels of challenge are identified within individual activities, and that design-and-make projects take account of small differences in the teacher’s performance expectations. By identifying the small steps and becoming familiar with them, a teacher then gains the confidence to provide a slightly more difficult level of challenge for children as and when appropriate.

There is a need for teachers to be so confident in their subject knowledge to be able to ‘think on their feet’. It is recommended (Design and Technology Association (DATA) 1996b) that a teacher build up a repertoire of familiar projects with different materials and processes. It may be preferable for a trainee to know three different design-and-make projects very well, and to understand the detailed progress within them, than to know ten projects in less detail. In identifying ways to help individual children progress, the detail is important and trainees usually find that their understanding of the progressive development inherent in a particular project grows each time they use it in the classroom. However, not all learners follow the same progression through a project and individual responses to a situation will provide information about how to modify teaching approaches.

For a variety of reasons, many children leave primary school without making significant progress in either designing or making. In a typical class of nine- to ten-year-olds, someone will be unable to use scissors well. Some children are unable to communicate their design ideas in high quality drawings by the end of Key Stage 2. One then questions what has happened during the child’s schooling that has left them with a less than satisfactory competence in using a simple tool, or in using drawing to communicate design ideas. It may be argued that particular children are not ‘good with their hands’ or that children make progress at different rates. This is indisputable since it is widely believed that children have varying aptitudes for different aspects of the curriculum, through either heredity or experience.

It is also known that progress through most subjects, including design and technology, is not linear, but more often viewed as a spiral in which we continually revisit concepts at a different level. Nevertheless, a child’s failure to perform at an expected level of competence usually indicates a failure in teaching, rather than arising inevitably from the child’s own genetic inheritance. The teacher is in the prime position of control within the classroom and it is the provision a teacher makes for each child that holds the key to success or failure. Of course, funding levels determine the extent to which a teacher may make appropriate provision and the importance attached to the subject by the school. The provision of clear curriculum leadership, whole-school policy documents, schemes of work and in-service provision demonstrate the level of support available.

Using the activities

The aim of this book is to provide a professional development resource for individual or group use and the activities provided in each chapter work effectively with children, trainees or teachers on in-service courses. Exploring the issue of progression usually meets with a positive response because many teachers lack confidence in their ability to identify ways of enabling children’s design and technology capabilities to progress. In schools, there is a heavy reliance on the long-term planning to provide the necessary progression. The purpose of this book is to encourage adults who work with children in educational settings to consider carefully the progress that individual children make in design and technology.

The assumption is that readers have a level of subject knowledge that allows them to understand the processes and techniques developed during the activities. The purpose of the activities is to develop and refine the ability to recognise specific needs and to cater for progression on an individual basis within the classroom setting. Activities are suitable for individual or group use. Some are specifically for teachers or trainees and others are for using with children. Some are useful at both levels. They have photocopiable sheets as a stimulus for group leaders to use in the best way to suit their purpose. The sheets will enlarge to A4 if required.

It is not the intention of this book to provide schemes of work or a host of ideas to implement straight into the classroom although there is an attempt to provide material within popular themes. The occasional suggested pupil worksheet is a stimulus for further development, but may be used directly with children if appropriate. The tasks are not generally open-ended design briefs. They are mostly focused tasks designed to explore specific processes as part of pedagogical development. Some of the activities may be joined together to form part of a larger project to facilitate looking at these issues through usual classroom practice. The aim is to develop practitioner expertise that enables reflection upon classroom events to take place and will subsequently inform planning for progression. The next three sections will attempt to clarify the nature of three important terms: continuity, progression and differentiation.

Continuity

Continuity and progression are terms often used in tandem. For example, all newly qualified and practising teachers ought to be able to ‘ensure continuity and progression within the design and technology work of their own class and with the classes to and from which their pupils transfer’ (DATA 1996a, p. 7). Subject specialists who are intending to become design and technology curriculum coordinators should also be able to ‘set appropriately demanding and progressive expectations for individual pupils of all abilities within their classes which ensure continuity and demonstrate an understanding of what represents quality in pupils’ design and technology work’ (DATA 1996a, p. 7). Many experienced but non-specialist teachers should also be able to perform at this level. Continuity is not defined by DATA (1995b), except as it refers to continuity in learning across Key Stages 1 and 2, between each year, within a year and from Key Stage 2 into Key Stage 3. It is important to separate continuity and progression because they mean different things in an educational setting. Continuity refers to the provision of experiences and content. Ensuring continuity within a class is relatively easy, because the class teacher has a clear view of the experiences provided to children through the year.

However, all the strands that DATA (1995b) refers to are not as easy to maintain. A school may provide continuity by ensuring that all children experience the same type of classroom process when being taught design and technology. To achieve this, in-service training is required together with classroom support from the coordinator. Lack of continuity occurs when teachers have different expectations of their children’s capabilities. For example, six-year-old children may have a teacher who expects them to complete annotated design drawings and to use them to inform making. The teacher of seven-year-old children may provide them with the design and expect all children to make exactly the same product. This is not the place to discuss the advantages or disadvantages of either approach, but merely to highlight the lack of continuity in the children’s experience. In such a situation, there is limited opportunity for children to make progress in developing their own design ideas and skills in designing at age seven.

In relation to content, children may make exactly the same products in different years of their primary schooling. Expectations may be different as the child becomes older, but the danger is that the child perceives it to be the same experience, loses interest and therefore makes little progress. This approach is quite successful if managed carefully. For example, in a classroom that contains three different age groups the same project may be completed with different materials and clearly more challenging expectations for each year group. It is important for the school to ensure that there is continuity of experience. One experience can flow into another across the year groups, for example, by ensuring the children experience textiles more than once, with different textiles in different projects. Continuity is an essential ingredient for progression, which is why the two concepts link so easily. Continuity in both content and process will provide better opportunities for the teacher to focus on children making progress.

Progression

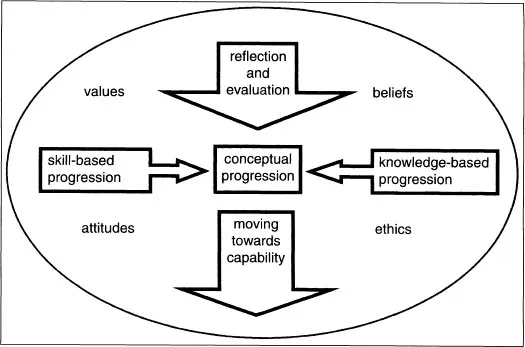

Capturing progression is no easy task because of the different strands within the subject. Figure 1.1 provides a model that may be useful to identify the relationships between strands of progression.

Figure 1.1 The relationships between different aspects of design and technology

The focus in some classrooms may be on a skill-based progression th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Photocopiable Activities

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Designing

- 3 Making

- 4 Moving Forward

- Bibliography

- Index