- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Readings in Risk

About this book

Developed for use as a reference work in graduate and undergraduate courses as well as for researchers, policymakers, and interested laypersons, the book is a unique collection of authoritative yet accessible journal articles about risk. Drawn from a variety of disciplines including the physical and social sciences, engineering, and law, the articles deal with a wide range of public policy, regulatory, management, energy, and environmental issues. The selections are accompanied by introductory notes, questions for thought and discussion, and suggestions for further reading.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Readings in Risk by Theodore S. Glickman,Michael Gough in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Basic Concepts

Introduction

Mankind has always sought to eliminate unwanted risks to health and safety, or at least to bring them under control. Its successes are impressive, as evidenced by advances such as the discovery of vaccines that prevent polio and smallpox and the development of building methods that enable stadiums and skyscrapers to withstand powerful earthquakes. Despite our best efforts, however, some familiar risks persist while others that are less familiar are found to have escaped our attention far too long and new ones continue to arise.

Ironically, some of the risks that are most difficult to manage or accept arise from technologies that are intended to improve our standard of living. The invention of the automobile, the advent of air travel, the development of synthetic chemicals, and the introduction of nuclear power all illustrate this point.

The respects in which the world is or is becoming an unhealthy or unsafe place to live and the views on how to allocate resources to do something about it are the subjects of continuing debates. These debates underline the need for clear concepts and useful definitions to help solve the risk problems that we face. The four papers on basic concepts in part 1 reflect much of the current thinking on these matters. While they all embody the idea that risk means the possibility of harm, they also demonstrate that conceptualization and definition are only the beginning of understanding risk.

In "Probing the Question of Technology-Induced Risk," M. Granger Morgan describes a conceptual framework in which two phenomena—"exposure processes" and "effects processes"—can produce changes in the technologically related risks borne by us and our environment. Depending on our perception and evaluation of any given risk, he explains, we either accept it or not, and if not, then we attempt to reduce our exposure to it or act to mitigate its effects. The need to decide which risks to address draws attention to the intriguing question of why some risks are more worrisome than others, and he sheds light on that subject as well.

In "Choosing and Managing Technology-Induced Risk," a sequel to the first paper, Morgan draws our attention to risk assessment and risk management. These two activities are motivated, he tells us, by the realization that individually and collectively we must decide first how much risk we can live with and then how we will deal with the risks we choose to limit. In practicing risk assessment, which he characterizes as part art and part science, the author warns against putting too much effort into the process of generating numerical values at the expense of exercising careful human judgment. When making decisions about which risks to abate and how much to spend to get the job done, risk managers must accept the fact that there are inevitable uncertainties and prepare to deal with the societal impacts of their decisions.

Authors Baruch Fischhoff, Stephen R. Watson, and Chris Hope develop the thesis, in "Defining Risk," that there is no single definition of risk. The particular situation determines, for instance, whether risks are assessed in terms of morbidity or mortality and whether they are limited to immediate effects or extended to include delayed effects. The appropriate measure of exposure to use when determining a fatality or injury rate also depends on the context, the authors say. Then they analyze the risks from alternative methods of generating electricity to demonstrate how the determination of risk can be influenced by the relative emphasis placed on various contextual factors.

Addressing the issue of acceptable risk in "Risk Analysis: Understanding 'How Safe Is Safe Enough?,' " Stephen L. Derby and Ralph L. Keeney suggest that acceptability depends on what it takes, financially or otherwise, to achieve reductions in risk. They argue that if one considers the advantages and disadvantages of all the available alternatives for diminishing a given risk, then by definition the best alternative is "safe enough." They dismiss as inappropriate the tenets that "only no risk is safe enough" and that "only the safest alternative is safe enough." The discussion then turns to the means by which technical, social, political, and ethical considerations enter into the decision process.

Probing the Question of Technology-Induced Risk

M. GRANGER MORGAN

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

If there were a top 40 for the hot problems of our day, risk would be high on the charts. Many people are writing about it. Private organizations and government regulators are trying to assess and manage it, Lobbyists and interest groups would like the public either to ignore it or to worry more about it. And, whatever action is taken, lawyers are thriving because of it. Why this big concern with risks?

The statistical evidence shows that Americans live longer, healthier, and wealthier lives today than they did at any time in the past. Perhaps, some economists argue, we worry more about risk today precisely because we have more to lose and because we have more disposable income to spend on risk reduction. Such economic factors are undoubtedly important, but they probably do not tell the whole story. Why, for example, do risks from new technologies—like microwave ovens, which present a relatively low probability of death or injury—often get more attention than older, well-established risks like motorcycles, which routinely are involved in the deaths of or injuries to substantial numbers of people? Why do people who have slept under an electric blanket every night for years suddenly become terrified about possible adverse health effects when a new 765-kilovolt power line is built a few hundred meters from their home?

Our ancestors, more resigned to death, disease, and injury, understood that nothing in life is risk-free. But we have done so well in reducing risks that now many seem to forget that no activity or technology can be absolutely safe.

With increasing frequency, scientists, engineers, and others who have thought carefully about risk have been arguing that the real problem is not the unachievable task of making technologies risk-free, but the more subtle problem of determining how to make the technologies safe enough. Most engineers find it rather natural to think about risk questions in these terms—to think, for example, about trading off the benefits of improved medical diagnostic capabilities against the risks of exposure to diagnostic X-rays. But engineers often become disturbed when they begin to discover that the question "How safe is safe enough?" has no simple answer.

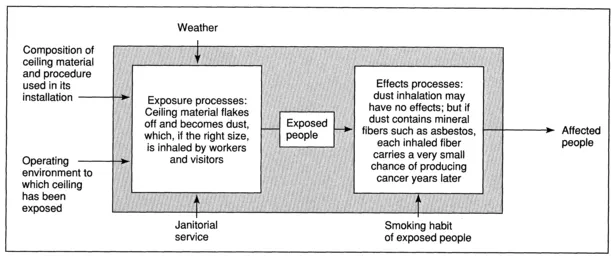

Figure 1. Does sound-proofing material sprayed on the ceiling of a room years ago in a manufacturing facility pose a health risk to visitors and workers? The answer depends upon the composition and history of the material and its application, a set of current environmental factors, and a set of exposure processes and effects processes.

Typical Examples of Risk

Some examples may help to develop a framework for thinking about technological risk to health, safety, and the human environment.

Each year visitors tour the U.S. Mint in Denver, Colo. Last summer some noticed that the ceilings in some of the work rooms, sprayed years ago with a layer of sound-proofing material to deaden the noise from the machinery, had begun to flake and strands of fibers could be seen dangling here and there, gently wafting in the breeze from open windows and ventilating fans. In some places visitors could reach up from the tour balcony and touch the ceiling. Did this old, flaking ceiling represent a health risk? To answer that question, the processes by which people are exposed to the chance of undergoing some change (exposure processes) and the processes by which these changes occur (effects processes) must be examined.

Through age, vibration, air motion, and perhaps human contact, pieces of ceiling fiber were falling off. The physics and chemistry of the situation determined how many of these fibers fell off and whether they fell off only as large chunks or also as small submicrometer particles. Other factors that probably influenced the amount and size of dust particles in the air included the way in which the janitors and maintenance people cleaned the machinery and floors, as well as the air-circulation patterns that were set up by the fans and open windows.

The human upper respiratory system is remarkably good at filtering out dust particles. But particles from a fraction of a micrometer to a few micrometers can enter deep into the lungs. Hence if the exposure process involved submicrometer ceiling particles, then some of these particles were probably ending up in the lungs of workers and a few in the lungs of visitors.

What is the possible effect of submicrometer ceiling particles lodged deep in the lungs? In the short run there probably are no effects at all. Dust is present in the air all the time, and in this case the amount of ceiling dust was fairly low. In the long run, the situation is less clear, depending strongly on the chemical and physical properties of the particles. There is a fair likelihood that the ceiling materials included mineral fibers, and asbestos in particular. If this were so, then there was a very small chance that 10 or 20 years after any given particle became lodged in a lung, cancer would develop. If the lung happened to belong to a smoker, the chance of cancer from exposure to asbestos might be as much as 15 times greater than the chance for a nonsmoker. These

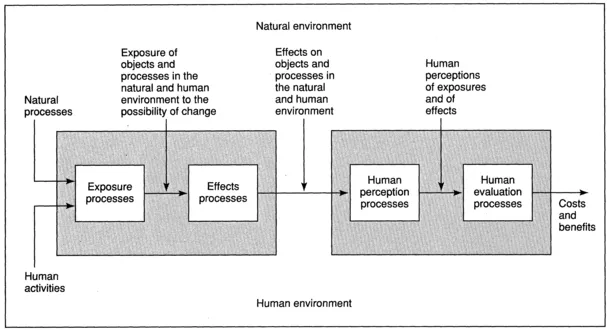

Figure 2. Interacting with the natural and human environments, exposure and effects processes involve objects (people, trees, houses) and natural events (weather). How these changes are perceived and evaluated by society and by people as "risks" depends in turn upon a set of perception and evaluation processes. All four processes shown—exposure, effects, perception, and evaluation—are also influenced by and can exert Influence upon the natural and human environments in ways not shown here.

exposure processes and effects processes are summarized in a simple diagram [figure 1]. (The U.S. Treasury Department asserts that tests have been unable to detect the presence of airborne fibers at the Denver mint.)

The exposure and effects processes associated with other risks can be identified in a similar way. In considering the possible health effects on those who spend their lives working on or near high-frequency radar-transmitting antennas, the exposure processes involve anything that brings microwave radiation and antenna workers together. For example, workers may be required to lubricate and adjust the moving parts of the antenna mount periodically while the system continues to operate. The exposure processes may also involve protective shielding and intensification effects that may modify the incident field strengths to which workers are exposed. Effects involve the electrochemical and biological processes that may affect human health adversely, such as cataracts after years of high-level exposure.

An electric power-distribution system outage is an example of a risk that does not involve a direct threat to human health. The exposure processes may include the presence of thunderstorms, distribution lines in exposed places, inadequate automatic reclosure equipment, and the absence of an automated distribution system. The effects processes might involve a series of events when a lightning strike occurs in close proximity to an exposed portion of the line, resulting in the automatic opening of protection equipment and the loss of power to a neighborhood.

Not All Exposure Is Bad

The results of exposures and of effects can be beneficial as well as harmful. In a coal-burning factory or power plant, for instance, that produces the air pollutant sulfur dioxide (S02) as one of its combustion by-products, exposure processes disperse the pollutants and carry some of the S02 to a field of alfalfa that happens to be growing in sulfate-poor soil. The S02 is absorbed by the alfalfa plants, but

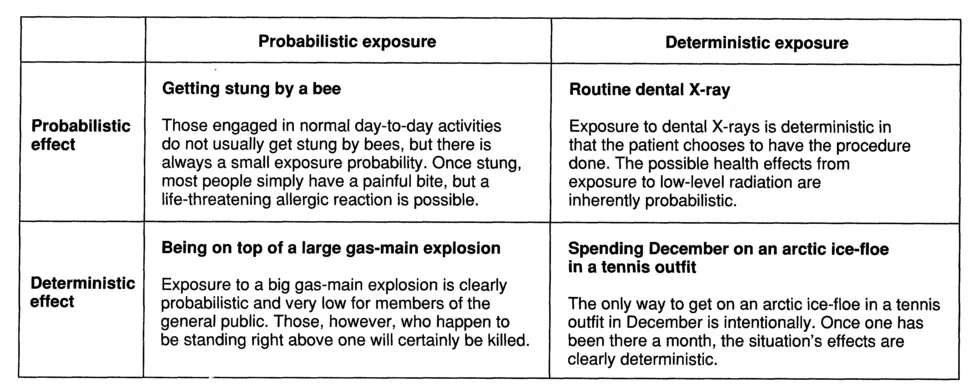

Figure 3. Risk Involves the exposure to a chance of injury or loss. The chance or probabilistic aspect of risk can be Introduced through exposure processes, effects processes, or both, yielding four possible combinations of exposures and effects.

because the concentration of SO2 in the air is low, toxic levels do not build up in the plants. Instead, the S02 is metabolized by the plant into sulfates and other sulfur compounds, some of which are needed for healthy plant growth. The resulting effects processes give rise to an increase in the total yield from the alfalfa field.

Hence, in the framework of figure 1, "exposure" does not mean exposure to risk. Instead, it is the exposure of people, objects, and systems to the possibility of some change. Similarly "effects" does not mean costs or losses. It is simply a list of changes.

Many dictionaries define risk as "the exposure to a chance of injury or loss." Whether people perceive a particular change in the world as an injury or loss depends both on the processes by which they perceive the change and the processes by which they evaluate it [figure 2].

The Chance Element

The chance, or probabilistic, element of risk may arise from the following:

- The values of all the important variables involved are not or cannot be known, and precise projections cannot be made.

- The physics, chemistry, and biology of the processes involved are not fully understood, and no one knows how to build adequate predictive models.

- The processes involved are inherently probabilistic, or at least so complex that it is infeasible to construct and solve predictive models.

In addition, the extent to which a process is viewed as certain or uncertain often depends upon individual perspective. An individual driver is likely to view automobile accidents as highly unpredictable events. But an insurance company can usually predict with remarkable precision the number of accidents its policy holders will have during t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- PART 1. BASIC CONCEPTS

- PART 2. RISK COMPARISONS

- PART 3. REGULATORY ISSUES

- PART 4. HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT

- PART 5. TECHNOLOGICAL RISK ASSESSMENT

- PART 6. RISK COMMUNICATION

- Suggestions for Further Reading