eBook - ePub

Capability and Quality in Higher Education

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Capability and Quality in Higher Education

About this book

The new focus in learning is on developing the individual's capability. This work looks at this in the context of improving skills, lifelong learning and welfare-to-work. It debates the issues within the setting of institutional strategies, work-based learning, skills development and assessment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Capability and Quality in Higher Education by John Stephenson, Mantz Yorke, John Stephenson,Mantz Yorke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Concept of Capability and its Importance in Higher Education

The quality of purpose

It has been fashionable to judge quality according to fitness for purpose, an approach which equates quality with efficiency and takes the purpose as unquestioned, given or imposed. The discussion of quality in this chapter focuses on the question ‘What is higher education for?’, looking at quality in terms of fitness of purpose. The capability movement began debating this issue in 1980 when it published its Education For Capability manifesto through the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) in London. This manifesto focused on the limited value of education when it is seen solely as the pursuit of knowledge and intellectual skills for their own sake. ‘Individuals, industry and society as a whole benefit’ the manifesto asserted, ‘when all of us have the capacity to be effective in our personal social and working lives.’ When couched in the context of rapid change, the manifesto implies that higher education should be judged by the extent to which it:

- gives students the confidence and ability to take responsibility for their own continuing personal and professional development;

- prepares students to be personally effective within the circumstances of their lives and work;

- promotes the pursuit of excellence in the development, acquisition and application of knowledge and skills.

Higher Education for Capability (HEC) was established by the RSA in 1988 to take these issues into the senior common rooms of the UK and, via its members overseas, to higher education in Australia and New Zealand. Through extensive discussions of the manifesto and its relevance in over 100 higher education institutions, HEC found considerable agreement for the development of student capability as an appropriate aim of higher education. The aim of this chapter is to explore the concept of capability more fully, to set capability in its wider context and to set out some of the issues facing higher education in its delivery.

The concept of capability

Capability is an all round human quality observable in what Sir Toby Weaver describes as ‘purposive and sensible’ action (Weaver, 1994). Capability is an integration of knowledge, skills, personal qualities and understanding used appropriately and effectively – not just in familiar and highly focused specialist contexts but in response to new and changing circumstances. Capability can be observed when we see people with justified confidence in their ability to:

- take effective and appropriate action;

- explain what they are about;

- live and work effectively with others; and

- continue to learn from their experiences as individuals and in association with others, in a diverse and changing society. (Stephenson, 1992)

Each of these four ‘abilities’ is an integration of many component skills and qualities, and each ability relates to the others. For instance, people’s ability to take appropriate action is related to specialist expertise which in turn is enhanced by learning derived from experiences of earlier actions. Explaining what one is about involves much more than the possession of superficial oral and written communication skills; it requires self-awareness and confidence in ones specialist knowledge and skills and how they relate to the circumstances in hand. The emphasis on ‘confidence’ draws attention to the distinction between the possession and the use of skills and qualities. To be ‘justified’, such confidence needs to be based on real experience of their successful use. In association with others in unfamiliar situations has clear implications for the kinds of students’ experience of higher education most likely to engender that justified confidence.

Capability is a necessary part of specialist expertise, not separate from it. Capable people not only know about their specialisms; they also have the confidence to apply their knowledge and skills within varied and changing situations and to continue to develop their specialist knowledge and skills long after they have left formal education.

Finally, capability is not just about skills and knowledge. Taking effective and appropriate action within unfamiliar and changing circumstances involves ethics, judgements, the self-confidence to take risks and a commitment to learn from the experience. A capable person has culture, in the sense of being able to ‘decide between goodness and wickedness or between beauty and ugliness’ (Weaver, 1994).

Capability and competence?

During the 1990s we have seen the development of competence-based national frameworks of vocational qualifications (NVQs) in the UK, Australia and New Zealand which are based on the needs of employers and the national drive to raise the qualification level and effectiveness of the work-force as a whole. These qualifications use industry standard competencies and performance indicators drawn from experienced practitioners. The UK Confederation of British Industry (CBI) has welcomed these developments and has found the use of NVQs beneficial in establishing industry standards and checklists for ensuring those standards are met (CBI, 1997). This competency approach is essentially a top-down control model which aims to secure the effective delivery of current services based on standards determined by past performance. Competence is about fitness for specified purposes.

Capability is a broader concept than that of competence. Competence is primarily about the ability to perform effectively, concerned largely with the here and now. Capability embraces competence but is also forward-looking, concerned with the realization of potential. A capability approach focuses on the capacity of individuals to participate in the formulation of their own developmental needs and those of the context in which they work and live. A capability approach is developmental and is driven essentially by all the participants based on their capacity to manage their own learning, and their proven ability to bring about change in both. Capability includes but goes beyond the achievement of competence in present day situations to imagining the future and contributing to making it happen. Capability is about both fitness of and for purpose. A changing world needs people who can look ahead and act accordingly.

Distinctions between disaggregated competencies and holistic capability have dominated more recent discussions on the concept and relevance of a capability approach. Compared with the late 1980s when the notion of capability was first formulated, there has been increasing emphasis on greater personal autonomy in education, employment and life, suggesting that it may be more useful to pursue this debate in terms of distinctions between dependent and independent capability.

Dependent or independent capability

The cartoonist Gary Larson depicts a group of sheep in a cocktail party, uncertain about where to stand and when to eat. ‘Thank God’, one says, ‘here comes a Border collie’. Sheep, of course, have all the skills for being a sheep – they are expert at both eating and standing. They do both, at the same time, all day. Put them in a cocktail party and they are totally lost, dependent upon the arrival of a controller to tell them what to do. They have the skills but not the confidence to use them when circumstances are totally different. If these sheep were capable (in the sense in which we use the term) they would have three extra attributes: an ability to learn for themselves, and to quickly fathom the new environment; a belief in their personal power to perform in new situations (they would have the confidence, having spotted the pasture discretely left by the host, to do something about it) and powers of judgement (they might even question whether it was appropriate for sheep to be at the party and simply leave).

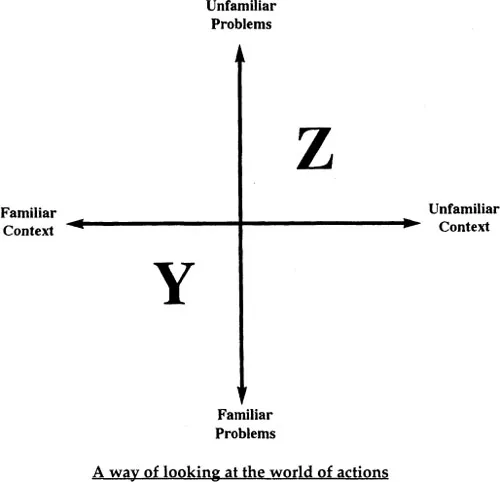

The Larson cartoon draws attention to the obvious limitations of a dependent mode of behaviour within a changing environment. For the purposes of the present argument, we can identify different situations in which varying degrees of independence are necessary (Figure 1.1). In our daily lives we can find ourselves moving from one type of situation to another, occasionally occupying more than one at the same time when different aspects of our work and lives come together.

Figure 1.1 Dependent and independent capability

Most of us operate, for much of our time, in position Y. In position Y, we are dealing with familiar problems for which we have learned familiar solutions. The context in which we are operating is also familiar. Position Y can apply to the work-place, the home, community activities or artistic pursuits. Good performance in position Y may require technical skills and knowledge of the highest order, or at the simplest level. We give students information about the context; the more complex the context, the more information we give them. We give them information about the kinds of problems they will meet, and details of the solutions which have been found to be effective. We might even give them practice in the implementation of the solutions and evaluation of their effectiveness. We seek to develop student capability in position Y by passing on other people’s experience, knowledge and solutions. Though no doubt effective in the context of position Y, the resultant capability is essentially a dependent capability. But position Y is not the whole of our experience. As indicated above, change is the order of the day. Many more of us will be spending more of our time having to operate in position Z. In position Z, we have less familiarity with the context and we have not previously experienced the problems with which we are faced. The slavish application of solutions perfected for familiar problems may have disastrous effects in position Z. To a large extent we are on our own, either individually or collectively. Very often, what distinguishes effective pilots, effective surgeons, effective social workers, effective teachers, effective builders and effective accountants is that they perform as well in position Z as in position Y.

In position Z we have to take much more responsibility for our own learning. By definition, we must inform ourselves about the unfamiliar context and not simply remind ourselves of what we were taught or trained to do. By definition, we must formulate the problems we have to deal with, not remind ourselves of problems previously learned. We must devise solutions and ways of applying them without the certainty of knowing the outcome, as a way of learning more about both the context and the problem. We need confidence in our ability to learn about the new context and to test possible ways forward from which we can learn. We need confidence in ourselves, and in our judgements, if we are to take actions in uncertainty and to see initial failure as a basis of learning how to do better.

When taking action in position Z, intuition, judgement and courage become important; there is no certainty of consequences based on previous experience. Specialist knowledge and skills are still relevant, but they are insufficient by themselves. It is necessary to appreciate their potential inadequacy, and to have the skills and confidence to enhance them. The solutions devised for the problems which are formulated will be essentially propositional in nature, developments from existing understanding. Evaluation of the consequences of actions taken in position Z will enhance our understanding of, and perhaps even improve, our performance in position Y.

Effective performance in position Z is likely to draw on all components of capability – specialist knowledge and skills, values and personal qualities. Key skills as defined by the Dearing Report (NCIHE, 1997) (the use of IT, communication, numeracy and learning how to learn) are clearly relevant to the above notion of capability, but only so far. They imply a fragmented, restricted, or simplistic view of capability. The Dearing Report comes nearer to describing independent capability when in paragraph 5.18 the Report gives primacy to

the development of higher level intellectual skills, knowledge and understanding’ because it ‘empowers the individual – giving satisfaction and self-esteem as personal potential is realized’ and ‘underpins the development of many of the other generic skills so valued by employers and of importance throughout working life.

Intellectual skills are an important part of the capacity to formulate problems in unfamiliar circumstances. The missing capability feature in the Dearing vision is the packaging of all of the above within a coherent strategy for ensuring students develop the capacity for ‘purposive and sensible’ action through the formulation of problems in unfamiliar situations.

Preparing people to be effective in position Z is important at all levels of education. It is, however, of particular importance for higher education because it is from our graduates that many of our key people, in work as well as in the community, are likely to be drawn. As the intake to higher education expands and becomes more diversified, the more this will be true. The nation needs its future engineers, business executives, architects, social workers, administrators and citizens to be as confident in position Z as they are in position Y.

Implications for delivering capability in higher education

Student capability is developed as much by learning experiences as by the specific content of courses. If students are to develop ‘justified confidence’ in their ability to take purposive and sensible action, and to develop the unsheeply characteristics of confidence in their ability to learn, belief in their power to perform and proven powers of judgement in unfamiliar situations, they need real experience of being responsible and accountable for their own learning, within the rigorous, interactive, supportive and, for them, unfamiliar environment of higher education. If, as a consequence of being responsible for their own learning they bring about significant changes in their personal, academic, vocational or professional circumstances they will also have justified confidence in their ability to take effective and appropriate action, to explain what they are about, to live and work...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Glossary

- About the authors

- Part 1: The Context

- Part 2: Building the Capability Curriculum: Some Reports from the Field

- Part 3: Autonomy and Quality

- Part 4: The Way Ahead

- Index