- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Practical Guide to Borehole Geophysics in Environmental Investigations

About this book

Borehole geophysics is frequently applied in hydrogeological environmental investigations where, for example, sites must be evaluated to determine the distribution of contaminants. It is a cost-effective method for obtaining information during several phases of such investigations. Written by one of world's leading experts in the field, A Practical Guide to Borehole Geophysics in Environmental Investigations explains the basic principles of the many tools and techniques used in borehole logging projects. Applications are presented in terms of broad project objectives, providing a hands-on guide to geophysical logging programs, including specific examples of how to obtain and interpret data that meet particular hydrogeologic objectives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Practical Guide to Borehole Geophysics in Environmental Investigations by W. Scott Keys in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Most environmental investigations of the subsurface in recent years have sought to determine the effects of contaminants on the groundwater system. The main purposes of such studies are to identify acceptable sites, locate and identify contaminants, identify migration pathways, predict movement, and guide remediation programs in both the saturated and unsaturated soil and rocks. Regardless of the source of pollution — landfill, industrial site, military base, or injection well, it has been necessary to drill test holes and monitoring wells to carry out these studies. Drilling and sampling these wells are expensive procedures, and borehole geophysics provides a group of techniques for obtaining much more information from such wells at minimal additional cost.

Borehole geophysics, as used in this guide, includes all methods for making continuous or point measurements down a drill hole. These measurements are made by lowering different types of probes into a borehole and by electrically transmitting data to the surface where they are recorded in digital or analog format as a function of depth. The measurements are related to the physical and chemical properties of the rocks surrounding the borehole and of the fluid in the borehole, to the construction of the well, or to some combination of these factors.

Almost all geophysical logging techniques were developed in the petroleum industry, and all oil wells are logged using some combination of these techniques. Most of the textbooks and technical reports published are written about petroleum applications, which differ markedly from groundwater and environmental applications. In addition, the equipment used for nonpetroleum logging is quite different from that used to log oil wells, and the cost of equipment and services tends to be much lower.

Chapters 1 through 7 of this guide describe general purposes, planning, and methods of utilizing borehole geophysics in the environmental field. Chapters 8 through 12 describe the various logging methods that might be used for environmental investigations. Chapter 13, on case histories, demonstrates how geophysical logs have been used at four environmental projects in different geohydrologic settings, with emphasis on the synergistic nature of logs. Chapter 14 is a glossary of logging terms used in this guide for those not familiar with the terminology, and the list of references cited should be consulted for more information.

1.1 BENEFITS AND LIMITATIONS OF LOGGING

The main objective of borehole geophysics is to obtain more information about the subsurface than can be obtained from conventional drilling, sampling, and testing. Although drilling a test hole or well is an expensive procedure; it provides access to the subsurface for geophysical probes from which many different kinds of data can be acquired for a cost usually much less than coring and making laboratory analyses of water and rock samples. Logs may be interpreted in terms of lithology, thickness, and continuity of aquifers and confining beds; permeability; porosity; bulk density; resistivity; moisture content; specific yield; source, movement, and chemical and physical characteristics of groundwater; and integrity of well construction. Log data are repeatable over a long period, and are comparable even when measured with different equipment. The repeatability and comparability provide the basis for measuring changes in a contaminant plume with time. Changes in an aquifer matrix, such as in porosity by plugging, or changes in water quality, such as in salinity or temperature, may also be recorded. Thus logs may be used to establish baseline aquifer characteristics to determine how substantial the future changes may be or what degradation may have already occurred. Logs that are digitized in the field or later in the office may be corrected rapidly, collated, and analyzed using computer techniques.

Most borehole geophysical tools sample or investigate a volume of rock many times larger than core or cuttings commonly extracted from a borehole. Some probes measure data from rock a number of feet beyond the immediate walls of the borehole and beyond that disturbed by the drilling process. Samples of rock or fluid from a borehole provide data only from sampled depth intervals after laboratory analysis. In contrast, borehole logs usually provide continuous data, can be analyzed in real time at the well site, and thus can be used to guide completion or testing procedures. Logs also aid the lateral and vertical extrapolation of geologic and water sample data or hydraulic test data from wells. Descriptive logs, written by a driller or geologist, are limited by their authors’ experience and purpose and are highly subjective. Geophysical logs may provide objective numerical values and frequently indicate geologic and hydrologic parameters that cannot be measured by other methods. Data from geophysical logs are used in the development of digital models of natural aquifer systems and of contaminant plumes and in the design of disposal or remediation systems. Many techniques used in surface geophysics are related closely to techniques in borehole geophysics, and the two should be considered together when setting up comprehensive environmental investigations. Data from some geophysical logs, such as acoustic velocity and resistivity, are also useful for interpreting surface geophysical surveys.

Geophysical logging cannot replace sampling completely, because background information is needed on each new geohydrologic environment to aid log analysis. A log analyst cannot evaluate a set of logs properly without information on the local geology and hydrology. Logs do not have a unique response; for example, high gamma radiation from shale is indistinguishable from that produced by granite. To maximize results from logs, at least one core hole should be drilled at each environmental site, and the core should be analyzed in a laboratory. If coring the entire interval of interest is too expensive, then intervals for coring and laboratory analysis can be selected on the basis of geophysical logs of a nearby hole. Laboratory analysis of core is essential either for direct calibration of logs or for checking calibration carried out by other means. Calibration of logs carried out in one rock type may not be valid in other rock types because of the effect of the chemical composition of the rock matrix.

Correct interpretation of logs should be based on a thorough understanding of the operating principles of each logging technique. For this reason, interpretation of logs in the petroleum industry is done largely by professional log analysts. In contrast, very few log analysts are working in the environmental field, so interpretation of logs for these applications is often carried out by hydrologists or geologists conducting the site investigation. This approach is valid as long as the earth scientist doing the log analysis has adequate training and experience in borehole geophysics.

A properly designed borehole geophysics program can reduce the cost of environmental investigations if the following steps are followed:

1. Plan the logging program on the basis of the information needed and the type of drill holes that will be available.

2. Drill and complete test holes and wells so that the construction optimizes results from sampling, testing, and logging.

3. Take core or cutting samples at depths where log response is relatively constant so that the samples will be representative and can be used for log calibration.

4. Control the quality of logs recorded by requiring complete labeling, calibrating, and standardizing.

5. Interpret logs as a set, based on a thorough understanding of the principles of each, with the aid of all background data available in the area.

1.2 LOGGING EQUIPMENT

A thorough understanding of the theory and principles of operation of logging equipment is essential for both logging operators and log analysts. An equipment operator needs to know enough about how each system works to be able to recognize and correct problems in the field and to select the proper equipment configuration for each new logging environment. A log analyst needs to be able to recognize malfunctions on logs and logs that are not run properly. The maximum benefit is usually derived from borehole geophysics, where operators and analysts work together in the logging vehicle to select the most effective adjustments for each log.

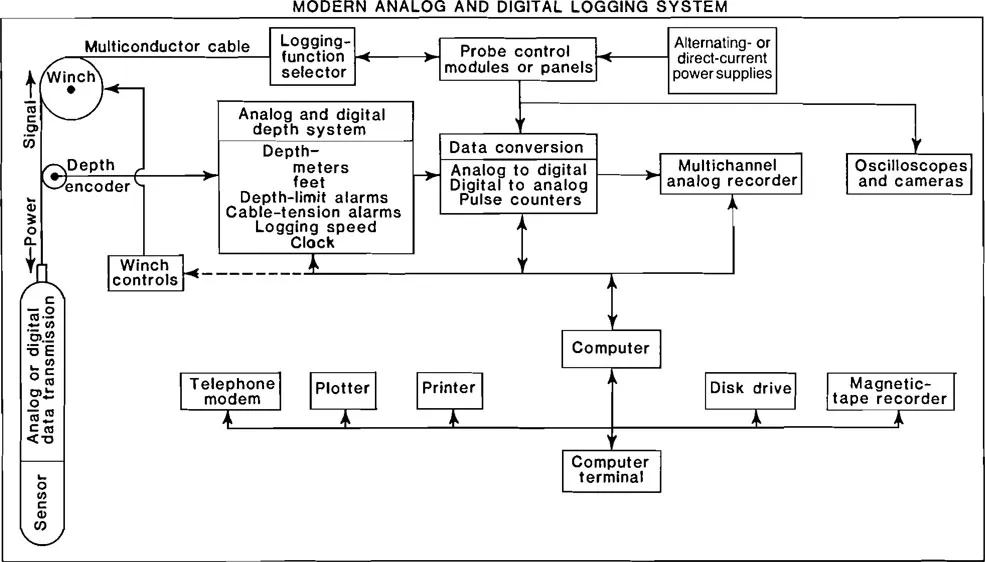

A logging system can be subdivided into subsystems or components to simplify the description. A schematic block diagram of the various possible components of an analog and digital logging system is shown in Figure 1.1. The logger components shown in this figure can be mixed or matched in the fashion of modern computer systems. The most recent logging systems are entirely digital and control of the logging equipment is done from a computer keyboard. Unfortunately, there is still a considerable amount of quite old logging equipment being used in the environmental field. Out-of-date equipment can still produce valid logs if it is properly maintained and calibrated and run by a qualified operator.

A short description of logging system components is included here. A brief description of each type of logging probe and ancillary equipment is included in the section on that type of log. Other related information is found in the sections of this guide on planning the logging program, log quality control, and calibration and standardization of logs.

Environmental logging equipment is usually mounted in a small truck or a van, but more easily portable logging equipment has become quite popular and more practical with the advent of notebook computers. Portable, or suitcase loggers, which can easily be carried and shipped as rentals, are almost all digital and computer controlled. Log display is on a notebook computer, and a permanent record is obtained from a printer. The equipment may be powered by an inverter running off a car battery. Winches usually hold a few hundred feet of single conductor cable. It is usually not possible to run complex logging probes using a small portable logger because of its size and additional surface instrumentation, but many of the smaller probes are the same as those operated on truck-mounted units.

Logging probes, also called sondes or tools, enclose the sensors, sources, electronics for transmitting and receiving signals, and power supplies. The probes are connected to a cable by a cable head screwed onto the top of the probe. Most probes are made of stainless steel or other noncorroding materials that are easy to clean at environmental sites. Electric-logging sondes often use lead electrodes; acoustic tools incorporate rubber and plastic materials for acoustic isolation and transmission. Some of these materials may not be easily cleaned. Probes vary in diameter from less than 1 in. to more than 4 in. (2.5 to 10 cm). Probes are available for environmental studies that will operate in 2-in. inside diameter casing (5.8 cm). Length varies from about 2 ft to 30 ft or more (0.61 to 9 m); weight may be as much as several hundred pounds. Some electric- and acoustic-logging devices are flexible; most are rigid. They are designed to withstand pressures of many thousands of pounds per square inch, which is based on the maximum depth they are designed to reach plus a safety factor for dense drilling fluids.

Many older probes transmit an analog signal to the surface for processing. The signal usually is a varying voltage or pulses that vary in frequency, which can be converted to digital data in the surface unit. Newer probes convert detected signals to a digital signal for transmission up the cable. With this system data processing, for example, dividing count rates, can be carried out in the probe to reduce cable losses. Data also may be transmitted from a large number of sensors. Digital probes offer the added advantage of easy switching and control from the surface by means of a computer keyboard.

Most older probes are axially symmetric and not side-collimated. That is, they send and receive signals 360 degrees from the probe axis; they are not intentionally decentralized. Many modern nuclear sondes, often called borehole-compensated, are decentralized and side-collimated, and employ several detectors. Decentralization is accomplished with caliper arms or bow springs and probes are side-collimated with an appropriate shielding material around the source of energy and the detector. The ratio of output from two detectors provides some degree of compensation for borehole effects. Compensated acoustic-velocity probes are centralized with bow springs or rubber fingers; they may employ two transmitters and four receivers to output an average signal. The operation of centralized probes in highly deviated drill holes can be very difficult. If centralizers are stiff enough to do the job, the probe will not go down the hole.

Figure 1.1

A modern analog and digital logging system. (Keys 1990)

A modern analog and digital logging system. (Keys 1990)

Most logging cable is double-wrapped with stainless steel wire to protect the insulated conductors inside and to serve as a strength member. This armor serves as one of the electrical conductors in single-conductor cable. Many portable water-well logging units still use single-conductor cable because it is lighter and cheaper than multiconductor cable. However, in recent years, a trend toward using four-conductor cable has occurred. Because it permits quantitative resistivity and acoustic logs to be run, it allows several logs to be run at one time, and it has greater strength for heavy probes and deep wells. Cable with seven conductors is standard for oil-well logging and is used in deep-water wells. The cable head often is the most troublesome component in a logging system. Electrical leakage in a cable head is common. If this occurs, the head usually has to be reinstalled, a time-consuming procedure.

Most winches are powered by alternating-current electric motors or driven mechanically or hydraulically from a power takeoff on the truck. They need sufficient power to break the cable if the probe becomes stuck in the borehole. If the winch is powered by an alternating-current generator, the generator must be oversized for the load, so that voltage drop does not affect the electronics. Some suitcase-type loggers have a hand-crank winch, but this is only practical to depths of 500 ft (150 m) with lightweight probes.

Logging cable is passed over a measuring sheave between the winch and the well. Electrical signals from an optical encoder, or selsyn, or a speedometer-type cable are used to transmit the movement of the measuring sheave to the logger-recording systems. The measuring sheave is precisely machined to provide accurate cable measurement and must be kept free of dry drilling mud or ice. The accuracy of cable-measuring systems needs to be checked periodically. When the measuring point on a probe reaches the reference point at the well head, the amount and direction of error is recorded on the log.

Control modules or panels are used to make the most of the adjustments necessary to run each type of log and provide power. The plug-in modular design is desirable, because the modules can be replaced readily in the event of a failure. Some modern logging trucks use a computer instead of modules to control logging functions The computer requests input from the operator on the way each log is to be run, and instructions are entered from a keyboard. These instructions may be transmitted to probes, power supplies, modules, and recorders.

A wide range of recorders are available for geophysical-logging equipment because almost any recorder manufactured today can be adapted to this use. Most of the analog recorders used are of the pen-and-ink type, with one to four pens. Chart paper is marked with vertical and horizontal divisions consistent with the logs to be made. In the United States a 1-in. scale in both directions, subdivided into tenths, is most common. In other parts of the world, metric divisions are used. A logarithmic horizontal scale may be used for logs that span a great range of values. Because log headings are not put on the log until after it is completed, all pertinent information needs to be written on the log as it is being recorded, including information about the well, probe, module adjustments, logging speed, and calibration. Log headings can be used as a reminder to assure that all pertinent information is noted (see Section 5.2).

Many modern loggers incorporate digital-recording equipment so that data from the probe may be displayed in digital and analog format. Although digital recording is becoming standard, an analog record or display is essential because of the need to study the log as it is being made. Without some kind of analog display, malfunctions or incorrectly selected logging parameters may not be recognized until it is too late for correction. In addition to use in computer interpretation, digitizing of logs on-site has several other benefits. Because the digital record contains all the raw data before it is sent to the analog recorder, no information is lost if the analog trace goes off scale. Digital recording allows the horizontal scale on the analog record to be selected at optimum sensitivity to display low-amplitude features. Valid logs may be plotted later from the digital data, even though the analog-surface equipment may have malfunctioned. In s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Environmental Applications of Borehole Geophysics

- 3 Planning an Environmental Logging Program

- 4 Log Analysis

- 5 Log Quality Control

- 6 Electric Logs

- 7 Nuclear Logs

- 8 Acoustic Logs

- 9 Borehole-Imaging Logs

- 10 Caliper Logs

- 11 Fluid Logs

- 12 Well-Construction Logs

- 13 Case Histories

- 14 Glossary

- 15 References

- 16 Index