![]()

1

SCHOOL BUILDINGS

Tim Brighouse

Introduction

Schools are so often the receptacles of all society’s hopes and disappointments. From economic woes to sporting failures, from concerns about mental and physical health and well-being to a rise in drug and drink problems, it’s usually the schools which are variously seen as the cause of the problem and/or the solution. Fall behind in PISA international tests on the basics, and it’s the schools’ fault. Terrorist attacks? Introduce the Prevent agenda and promote ‘British Values’ – in the schools.

When schools are on the receiving end of so many government demands, they can easily assume a defensive stance or succumb to giving attention to the urgent rather than the important. There are therefore two tasks for our schools: first, they need to understand how best to improve what they decide to do; second, in deciding what they do – the purposes of schooling – they need to have a realistic view of what their pupils are likely to need (in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes) to deal successfully with what the future will bring and to feel equipped to shape that future while at the same time living by the time-honoured values of civilisations.

This has always been the task of schools, but as the pace of change has accelerated, the expectations on schools have grown, as has the concomitant expectation that they will respond. Deciding what are the ‘breakable plates’ and determining what is essential in schooling’s purposes remain the elusive task of school leaders.

How do schools improve what they do?

Getting the buildings and school environment right, and designed in such a way as to be fully conducive to the vital work of the schools, is of course an essential ingredient to schools’ success in preparing youngsters for life as fulfilled and contributing adult citizens. Essential, but not sufficient. The question that has bedevilled educators and politicians is, “What, in addition to the formidable task of securing a creative secure and stimulating environment through brilliantly designed buildings, will make children’s educational experiences most conducive to their making the best of their adult lives, both for themselves and for others?”

Michael Rutter’s research for his book Fifteen Thousand Hours (Rutter, Maughan, Mortimore, & Ouston, 1979) taught us for the first time that school practices as a whole, as well as those of individual teachers, affected pupils’ outcomes. The study of school improvement practice since, by researchers, politicians and practitioners, has grown in intensity under the twin pressures of a natural wish to achieve the best for as many pupils as possible and a tough accountability system imposed by successive national governments through the introduction of tests at various ages to supplement GCSE and A-level exams as well as the establishment of Ofsted and its accompanying school inspection system. Inevitably, such an explicit system of accountability has caused a focus on that which can be easily measured, sometimes at the expense of assessing and recognising what might be less measurable but equally important.

In short, is the yardstick by which we measure a school’s success flawed? And if it is, what might we do to create a better one?

It is possible to hold schools accountable for these other valuable but less measurable aspects of schooling effectiveness, but, so far, English governments1 have shown little interest in doing so, even though they have been in the vanguard of ‘tough accountability’ and, in the process, finding impressively thorough ways of assessing matters such as pupils’ and schools’ test and exam results in basic skills and a traditional knowledge-based curriculum, pupil attendance and exclusions. This has been achieved mainly through Ofsted inspections of schools, backed by annual league tables of test and exam results. Even within such a ‘testing what we can measure’ agenda, governments have focused on the traditionally academic, rather than the vocational2 and practical, and have chosen to put less emphasis on the expressive and performing arts.

Later we shall examine ways of defining more clearly the broader purposes of schooling and the means of giving them greater importance. First, however, we need to sketch out what we have learned about how schools can be improved, whatever the agreed purposes may be. We have learned much.

The first and most important lesson is that ‘context’ is all-important to school outcomes. ‘Context’ is multifaceted. The quality of teachers and school leaders is obviously vital and differs significantly from school to school. So too do the pupils: it is one thing to try to educate the privileged children of rich and /or supportive parents in a public or grammar school, and quite another to teach children with a vast range of challenges in a comprehensive, secondary modern or special school. ‘People’ therefore comprise one variable of context.

Another is ‘place’, whether of culture or location. For example, under the pressure of international tests of pupil outcomes (TIMS, PIRLS and especially PISA),3 politicians eagerly engage in what has come to be known as ‘international tourism’ in policymaking. In the process, it is often too easily assumed that what works in Finland, Singapore, South Korea or Shanghai might apply as well in England, where cultural assumptions and values are very different. Moreover, within our own United Kingdom, there are also significant differences among the cultural assumptions within Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and England, respectively. Even within England, some would argue that there are differences in the likelihood of successful school outcomes, affected by the availability of employment or family expectations as well as whether the school is in a rural or heavily urbanised setting.

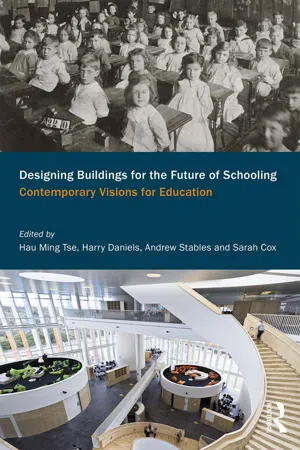

The major focus of this book is on another contextual variable in ‘school improvement’, namely the school building and its immediate surroundings. I confess to a shameful envy whenever I visit a major, or even minor, public school. Sometimes it can take five minutes to drive from the lodge to the splendid main buildings, which so often fulfil the Victorian head teacher’s advice to ‘surround them with things that are noble’. The state-provided schools so often offer a less conducive model of school building and surrounding environment. Rationing of money for building and the running of state-provided schools means that we spend about two-thirds less on the education of 93% of our children than we do on the 5% who attend the best ‘public’ schools.

If ‘people’, ‘place’ and ‘buildings’ are three contextual variables in school improvement, there are two others – ‘time’ and ‘purpose’. They are closely interwoven. Attlee’s post-Second World War government (which, following Butler’s Education Act of 1944, set the scene for the education of so many of the current generation including my own contemporaries) was affected by the war years and the depression that had preceded it. His government ushered in what might be called an age of ‘Hope, Optimism and Trust’ that, in education at least, was to last until the late 1960s. During that period, successive central governments (both Labour and Conservative administrations) trusted educators, whether in schools, colleges or universities, to determine what should be taught (‘the curriculum’) and how it should be taught (‘pedagogy’). Local Education Authorities (LEAs) within local government could also be trusted to administer and manage the system, which had been designed in general terms by the 1944 Act. There was nothing narrow about its purpose. Butler himself had been much influenced by William Temple, from whom he quotes approvingly in his Art of the Possible. Temple, who had been variously a head teacher and President of the Workers’ Educational Association before becoming Archbishop of Canterbury, memorably set out what he regarded as education’s overall purpose in a modern civilised society as follows:

Until Education has done more work than it has had an opportunity of doing, you cannot have a society organised on the basis of justice, for this reason…. that there will always be a strain between what is due to a man in view of his humanity with all his powers and capabilities and what is due to him at the moment of time as a member of society with all his faculties still undeveloped, with many of his tastes warped, with his powers largely crushed.

Are you going to treat a man as what he is or what he might be? Morality, I think, requires that you should treat him as what he might be, as what he might become…and business requires that you should treat him as he is.

You cannot get rid of that strain except by raising what he is to the level of what he might be. That is the whole work of education. Give him the full development of his powers and there will no longer be that conflict between the man as he is and the man as he might become.

And so you can have no justice as the basis of your social life until education has done its full work. And then again, you can have no real freedom, because until a man’s whole personality has developed, he cannot be free in his own life…..And you cannot have political freedom any more than you can have moral freedom until people’s powers are developed, for the simple reason that over and over again we find men with a cause which is just… are unable to state it in a way which might enable it to prevail….there exists a form of mental slavery which is as real as any economic form….We are pledged to destroy it…it you want human liberty, you must have educated people.

In a similarly ambitious and optimistic vein, Butler’s Act and the Physical Education and Recreation Acts of the 1930s urged LEAs to promote the physical, mental and spiritual well-being of their communities. LEAs were therefore busy in the 25 years that followed, not simply in supporting schools directly but also in setting a generally positive educational climate in the communities they and their schools served. In discharging the first set of these responsibilities, LEAs built new schools for the growing post-war population and for accommodating more pupils, as the school leaving age was raised on two occasions.4 They also created and expanded advisory and inspection services to support schools and their teachers and set up support services for schools, such as Education Welfare Officers and Youth Employment (Careers) teams. In interpreting their wider role, LEAs established youth services, extended their pre-war network of adult education courses, bought Outdoor Pursuits and residential centres, built new (and extended existing) colleges of further education and were trusted to oversee the governance and management of a new network of teacher training colleges and colleges of advanced technology, some of which subsequently became polytechnics and then universities.

That age of ‘Hope, Optimism and Trust’ in an agreed common purpose involved a partnership of central and local government and schools, which was characterised by trust that each would play their part in ‘building a new Jerusalem’ in which there was a general acceptance that ‘education was an unquestioned good thing’. The balance in that partnership was heavily reliant on LEAs as the engine room of development. Central government set the broad aims and had a few direct powers (mainly three: first, ‘securing a sufficient supply of suitably qualified teachers’; second, ‘rationing and approving the details of school building programmes’, and third, ‘approving the removal of air-raid shelters’. In discharging the second of these, the Ministry’s Architects and Buildings branch was an active guide in the design of school buildings.).

The age of ‘Hope, Optimism and Trust’, however (and perhaps inevitably), eventually gave way to another age, one of ‘Doubt and Disillusion’. It is difficult to determine when exactly this happened, although student unrest in 1968 had caused an unhappy Prime Minister to summon Vice Chancellors to a meeting in Downing Street to explain the causes. An oil crisis soon followed and there was a series of Black Paper publications, popularised by the media, which suggested that the basics were not being given sufficient attention by the schools. Callaghan’s Ruskin speech of 1976 characterised the ‘Doubt and Disillusion’.

In its turn, this second post-war educational age gave way to a third, one of ‘Markets and Managerialism’, which might fairly be associated with Margaret Thatcher’s access to the premiership after the 1979 General Election. Sometimes dubbed as being an example of neo-liberalism, her government’s educational White Papers were peppered with what appeared to be mantra words such as ‘choice,’ ‘autonomy’, ‘diversity’, ‘excellence’ and ‘accountability’. These were promoted by measures required by legislation. ‘Choice’ implied that parents needed choice of school, although they were arguably misled since, clearly, absolute choice could not be guaranteed because school size is not without a limit. In reality, the most that successive Education Acts have given parents is the ability to express a ‘preference’ of school for their child to attend. ‘Choice’, however, in those early days of ‘Markets’, did not extend to pupils or schools having choice in the curriculum, which was prescribed nationally and described as ‘broad and balanced’, thus enabling comparisons of different schools’ performance to be made. ‘Autonomy’ referred to the autonomy of individual schools, which was encouraged by legal imperatives such as delegation of decision-making over budgets, initially called Local Management of Schools. A recurring theme has been the wish to discourage schools from being dependent on their maintaining local authorities. ‘Diversity’ over the years has been encouraged through establishing different types of schools. Part of the 1944 Education Act was a ‘settlement’ of the respective roles of the state through local education authorities and the voluntary sector, mainly in the form of the churches and other faiths, which have run voluntary-aided schools complementing ‘county’, later designated ‘community’, schools. As the need for more diversity was encouraged, new forms of diversity in the provision of schools were devised. First there was ‘grant-maintained’ status.5 Then there were ‘specialist schools’, as well as ‘foundation’ and ‘trust’ schools. More recently there have emerged ‘academies’ and ‘free schools’ (both, in effect, revivals of the grant-maintained model. By such diversity in schooling, backed by each school’s autonomy, in the context of increased parental choice and the publication of school outcomes, a quasi-market in schooling has been created. Competition among and between schools is thereby encouraged as their results are published, and the parent, as consumer, makes choices among an array of schools following roughly the same curriculum.

The case for adding the word ‘Managerialism’ to ‘Markets’ as an apt descriptor of the ‘Age’ rests on two factors. First, there is the need for regulation and action when either the purposes of education need to alter to reflect changed circumstances or, as is inevitable in a competitive market, some schools succeed and others fail. The consequent need to make arrangements for pupils in such ‘failing’ schools is obvious. This task was initially left to local authorities, but the emergence of academies has increasingly involved central government, through a set of Regional Commissioners, in clearing up the mess involved in failing schools. Inevitably a prescriptive, hands-on management occurs in these cases. It could be argued that management does not necessarily imply managerialism. Over the years, however, the product of so much legislation – there were just two Education Acts of Parliament between 1944 and 1980; there have been almost 50 since – has been to centralise power at the expense of local government and, in some important respects, of the schools. Successive Secretaries of State, in consequence, empowered by so many Education Acts, have not been able to resist meddling in what schools do, so they have pronounced not just on the curriculum and what is taught but on how it is taught.6

It is tempting for a Secretary of State to want to make a mark, not just for reasons of legacy, but sometimes as a means of political advancement and occasionally as a personal whim. Almost all incumbents of the post since the Education Act of 1988 have been guilty of unnecessary and unwarranted interference in matters best left to local decision, whether by the schools themselves or by local authorities.7

LEAs have progressively been stripped of educational powers and responsibilities during the period of “Markets and Managerialism”. First, the colleges of further education were removed from their influence, along with the colleges of advanced technologies, polytechnics and colleges of education. Successive iterations of the rules of local financial manage...