- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Curriculum Planning with Design Language provides a streamlined, adaptable framework for using visual design terminology to conceptualize instructional design objectives, processes, and strategies. Drawing from instructional design theory, pattern language theory, and aesthetics, these ten course and unit design principles help educators break down and clarify their broader planning tasks and concerns. Written in clear, direct prose and rich with intuitive examples, this book showcases insights leading to effective curriculum design that will speak equally to pre-service and experienced educators.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Curriculum Planning with Design Language by Ken Badley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Classroom Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

DESIGNING INSTRUCTION

Teachers who give some time to design units before they start to plan instruction can simplify and streamline the planning process and increase their students’ self-efficacy. In this book, I offer ten design principles which, taken together, form a kind of language for unit design. Implementing any of these principles alone would help produce more elegant units and lead to improvements in student learning. Taken and used together, these principles form a powerful framework for unit design.

This chapter begins with a brief review of teachers’ typical approaches to planning instruction. I follow that by making a distinction between two important concepts, design and planning. While these two concepts are obviously connected, they need to be distinguished very carefully for my purposes here. In the third major section, I trace the immigration of design thinking into education, a process that divides roughly into four periods.

How Teachers Plan Instruction

Teachers take a host of factors into account when they plan instruction. First and obviously, they need to help their students learn what, for lack of a better term, I will call the curriculum. This learning ranges from “make sense of problems and persevere in solving them” (grades 3–5 mathematics in Massachusetts) to understanding “What makes a community?” and “How do I fit in?” (grade 1 social studies in Alberta). Planning must take into account the published curriculum standards but, in a sense, these standards are just the beginning. Teachers need to help students learn 21st-century skills, although the jury has not yet agreed on precisely what those are. From one source or another—perhaps these mandates are simply in the air that teachers breathe—they hear that they must also be front-line responders to society’s need for students to be technologically proficient, or familiar with anti-bullying strategies. Schools shoulder some of the burden for sex education and for raising environmental awareness. Presumably, teachers are to incorporate all this teaching and learning into the courses and units already on the books, courses such as social studies and mathematics.

Teachers also plan instruction in light of several realities related to the calendar. They work within the constraints of an annual calendar and several national holidays. School jurisdictions and individual schools set holiday breaks, as well as dates for teacher professional development, teacher conventions, parent conferences, staff meetings, assemblies, sports days, and even school concerts and plays.

In addition to accommodating all these practical and logistical concerns, teachers must take learning theory into account in their planning; they must consider what students already know and scaffold new learning onto old knowledge. By the day they graduate from their teaching program, new teachers will have heard repeatedly about learning styles and multiple intelligences. During their various in-school placements, they will likely already have met students who have their own Individual Learning Plan or Individual Education Plan because of a learning disability or behavioural tendency. They may also have worked with talented and gifted (TAG) students, some of whom are mainstreamed and others of whom are pulled out of class for daily or weekly special programming. To my point, when they plan instruction, teachers need to take a range of idiomatic concerns into consideration.

In the upper grades and in higher education, educators must consider the conceptual structures within a field of study. Academic disciplines comprise networks and hierarchies of concepts that stand in various kinds of relationships to each other. Students must understand some concepts before they can learn others. In chemistry, valence precedes compound. In mathematics, integer precedes fraction. In social studies, government precedes parliamentary democracy. In the academic disciplines, the networks and hierarchies of concepts, the accepted tests for evidence, and the canons and landmarks—taken together—comprise a disciplined way of viewing an aspect of the world. Teachers in secondary and higher education induct their students into the disciplines and into those disciplined ways of examining the world (Hirst & Peters, 1970). By necessity, educators at these levels must consider the respective disciplinary structures when they plan their instruction.

Finally, legislative factors impinge on teachers’ planning. Teachers do their work in light of a Schools Act or Education Act passed by their respective nation (if there is a national education system) or by their state, canton, or province (if the nation’s constitution passes the responsibility for education down). Those respective Acts shape most aspects of the operation of schools and of teachers’ professional work. Teachers need to take very serious account of this legislation because it literally governs their work. In addition to that overarching legal framework, school districts add their own policies, determine new mandates for their schools, and declare local initiatives. Finally, individual schools add to the mix.

In summary, when planning instruction, teachers take a host of factors into account. Both pre-service teachers and in-service teachers know about these many necessary considerations. This is a theme that runs through the research on how teachers plan (Martin, 1990; Masterman, 2009) and it partly explains why teachers tend to concern themselves more with the immediate questions of pedagogical content and resource materials than with design principles. Given the range of factors teachers must consider when planning and the number of classes per day that they must plan for, no one should be surprised that in planning instruction some teachers look mainly to the textbook and to teaching materials they have available from previous years. John Holt’s book What Do I Do Monday?(1995) has resonated with teachers over several decades not just because it is packed with teaching ideas but because its title catches what, for so many teachers, is the most pressing question. No one should be surprised about the growth in popularity of the work of Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins and their idea of planning backwards by design(1999, 2005, 2013). In the rush to get ready for each day, one can easily focus more on what one’s students will study—on what the class will “do”—and forget to ask about the learning outcomes one is aiming at. In fact, at its worst, this focus on what one will do on a given day can be reduced to “What pages of my binder will the class copy down today?” or even “Which PowerPoint deck from the textbook publisher will I click through today?”

McTighe and Wiggins have reminded generations of teachers to identify the desired learning outcomes first, then to ask what assessments would indicate that students have met those outcomes, and then to ask what instruction and activities would enable students to succeed on those assessments. The backwards-by-design planning model makes complete sense. One almost wishes McTighe and Wiggins had never had to point it out.

In light of the planning and instructional pressures on teachers (which I treat again in Chapter 12), no one should be surprised that most teachers give little thought to design, and that they go straight to planning (Kerr, 1983; Koh & Chai, 2016; Koh, Chai, Wong, & Hong, 2016). Planning is obviously necessary. In planning, the teacher makes decisions about what to teach. But planning, by itself, offers no principles about fitting instructional plans into the rhythms of the teacher’s own life, about the energy teachers and students have for learning on any given day, about the effects of repetition and variety, or about the need to breathe somewhere in the middle of a six-week stretch of classes with no long weekends. Even those who adhere most closely to backwards by design or universal design for learning still need to project how things will flow from day to day and week to week. What I call planning does not offer much to the teacher needing to make those bigger projections. What I call design addresses that need directly. Because these terms both figure centrally in discussion of teachers’ work, and because many people treat them as synonyms, I will now distinguish the two at some length.

Two Concepts: Design and Planning

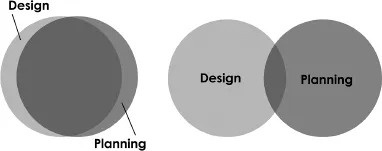

The previous section included a possibly intimidating catalogue of factors and forces that teachers must take into account when they plan instruction. As I noted previously, I believe that teachers who engage in design before they start to plan not only simplify and streamline their planning process but also increase their students’ self-efficacy. Before we dive too deeply into a discussion of this approach, I must distinguish what I mean by design from what I mean by planning. A majority of participants in the planning conversation employ these two terms interchangeably, their usage represented by the Venn diagram on the left side of Figure 1.2. Reading a few pages in most books whose titles include phrases such as unit design, curriculum design, instructional design, and course design will reveal that the authors of those books are writing about planning, whether it is from day to day, week to week, or semester to semester. In essence, those who speak of design this way are asking these questions: “Given that students need to learn these things, what should they study first, second, and third? What must be included and what may be omitted?”

Using the word design to designate planning—what I call undifferentiated usage—is neither right nor wrong and I cannot legislate other people’s linguistic preferences. My purpose in this section is only to note common usage and not to criticize those who speak of design in an undifferentiated way. That said, I am among the minority of users who would prefer the Venn diagram on the right side of Figure 1.2, that is, who do not equate the two but who instead want to restrict the word design to its artistic, aesthetic sense. For my purposes here, I will stipulate definitions of both terms and use them throughout the book, taking care to speak of design only in a differentiated way, that is, as distinct from planning.

Let me offer the two stipulated definitions. By planning, I mean the process of deciding what the students and their teacher will do in a given day, week, month, or term. For example, a university instructor might plan to work through the syllabus and lead a tour of the course wiki on the first day of the semester, and plan on the second day to give the first of three lectures on the major upheavals that ended the Medieval Period. In an elementary classroom, a teacher might plan to have the students fill out the first two columns of a three-column KWL sheet (what I Know, what I Would like to learn, what I Learned) as her introduction to a new unit on electricity and magnetism. If she were familiar with Visible Learning and Harvard’s Project Zero (2013), she might favor an adaptation of the KWL sheet and plan to ask her students to fill in the first column with what they Think they know. In these examples, teachers are planning what they and their students will do in class, in this case, on the first day of a new unit. I will use the word planning throughout the book to designate this kind of activity.

Of the two terms, design presents us with more problems, the first of which may be that the design field itself has struggled to define this key term (Barab & Squire, 2004; Cross, 1999; O’Donnell, 2004; Pirolli, 1991; Reigeluth, 1999; Reigeluth, Beatty, & Myers, 2016; Schatz, 2003). As an educator, not a professional designer, I will not try to solve here what the design community has failed to solve. However, the concept needs clarification for there to be productive conversation about the design thinking that I believe needs to precede planning. With the word design I refer to questions of form and shape, symmetry, beauty, line, coherence, elegance, and even accessibility by students. In the chapters that follow, I restrict design to the process of framing unit and course planning aesthetically. Framed aesthetically, planning is preceded by questions such as these: What simple, elegant structure underlies this unit (Chapter 12)? How can I reveal that structure ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Designing Instruction

- 2 Introducing the Patterns

- 3 Strong Centres

- 4 Boundaries

- 5 Entrances and Exits

- 6 Coherence and Connections

- 7 Green Spaces

- 8 Public and Private

- 9 Repetition and Variety

- 10 Gradients, Harmony, and Levels of Scale

- 11 Master Plans and Organic Development

- 12 Agile, Light Structures

- 13 Agile Unit Design

- 14 Conclusion

- Author Biography

- Index