- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Adoption, Race, and Identity is a long-range study of the impact of interracial adoption on those adopted and their families. Initiated in 1972, it was continued in 1979, 1984, and 1991. Cumulatively, these four phases trace the subjects from early childhood into young adulthood. This is the only extended study of this controversial subject.Simon and Altstein provide a broad perspective of the impact of transracial adoption and include profiles of the families involved in the study. They explore and compare the experiences of both the parents and the children. They identify families whose adoption experiences were problematic and those whose experiences were positive. Finally, the study looks at the insights the experience of transracial adoption brought to the adoptive parents and what advice they would pass on to future parents adopting children from different racial backgrounds. They include the reflections of those adopted included in the 1972 first phase, who are now adults themselves.This second edition includes a new concluding chapter that updates the fourth and last phase of the study. The authors were able to locate 88 of the 96 families who participated in the 1984 study. Bringing together all four phases of this twenty-year study into one volume gives the reader a richer and deeper understanding of what the experience of transracial adoption has meant for the parents, the adoptees, and children born into the families studied. This landmark work, will be of compelling interest to social workers, policy makers, and professionals and families involved on all sides of interracial adoption.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adoption, Race, and Identity by William Laufer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Transracial Adoption: An Overview

The history of adoption is the history of hard-to-place children. Adoption agencies historically have attempted to equate a child’s individual characteristics with those of the intended adoptive parents: “A child wants to be like his parents . . . parents can more easily identify with a child who resembles them ... the fact of adoption should not be accentuated by placing a child with parents who are different from him.”1 Not only were similar physical, and at times intellectual, qualities seen as important components in adoptive criteria, but identical religious backgrounds were defined, at times by law, as essential.2 Thus the battle of transreligious adoption preceded the movement toward trans-racial adoption, and it was not until the conceptual and pragmatic acceptance of transreligious adoption occurred that transracial adoption could, and did, develop.

As adoption moved toward becoming an acceptable means to deal with children who needed parents and couples who wanted children, so too did social work evolve into a recognized discipline. This relationship was not coincidental. Adoption agencies are a relatively new phenomenon. Historically most adoptions resulted from negotiations between attorneys for potential adoptive parents and an orphanage or a private physician whose patient wanted to surrender a child. The natural parent’s rights would be waived, and the court would usually grant the adoption petition. A gap existed, however, between a couple’s desire to adopt and the courts’ ability to determine whether the petitioners would indeed be adequate parents. Social work, or what was to develop into social work, sought to fill this gap by being the advocate for couples who wanted to adopt and for women or institutions who wanted to surrender their children.

Transracial and intercountry adoption began in the late 1940s, following the end of World War II, which left thousands of homeless children in many parts of the world. It gained momentum in the mid-1950s, diminished during the early 1960s, rose again in the late 1960s, and began to decline in the mid-1970s. When our first volume was published in 1977, transracial adoption had almost ceased to exist. For example, of the 4,172 black children who had been adopted in 1975 by unrelated petitioners, only 831 were placed with white families.3

The development of transracial adoption was not a result of deliberate agency programming to serve populations in need, but rather an accommodation to reality. Social changes regarding abortion, contraception, and reproduction in general had significantly reduced the number of white children available for adoption, leaving non white children as the largest available source.4 Changes had also occurred regarding the willingness of white couples to adopt nonwhite children. Whatever the reasons, in order to remain “in business,” adoption agencies were forced by a combination of social conditions to reevaluate their ideology, traditionally geared toward the “matching” concept, in order to serve the joint needs of these two groups.

The Matching Concept

The assumptions of matching are simple, but naive. In order to ensure against adoptive failure, adoption agencies felt that both the adopted child and his or her potential parents should be matched on as many physical, emotional, and cultural characteristics as possible. The most important were racial and religious characteristics.

Thus it was not uncommon for potential adoptive parents to be denied a child if their hair and eye color could not be duplicated in an adoptable child. The hypothesis of matching was one of equalization. If all possible physical, emotional, intellectual, racial, and religious differences between adopter and child could be reduced, hopefully to zero, the relationship stood a better chance of succeeding. So ingrained was the matching idea that its assumptions, especially those relating to religion and race, were operationalized into law under the rubric of a “child’s best interests.” Seventeen states, including the District of Columbia, had at one time or another statutes pertaining to the religious matching of adopted children and parents.5

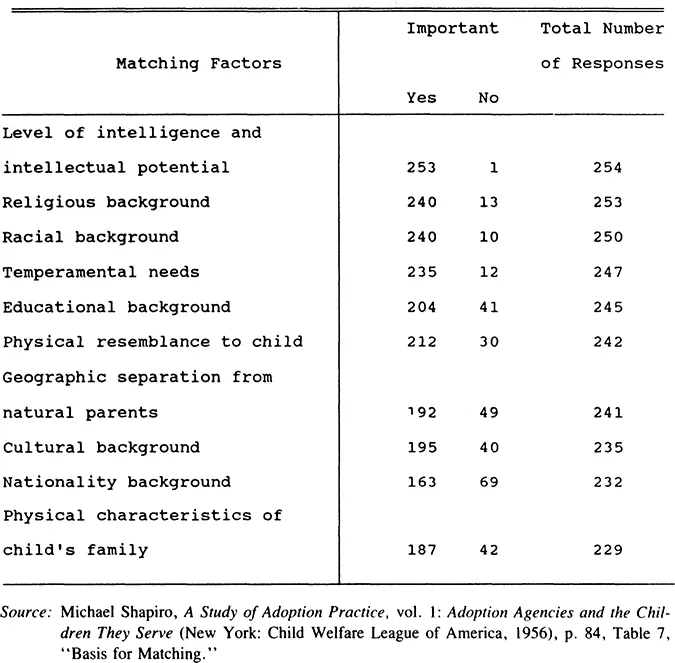

A 1954 study requested adoption agencies to indicate whether certain factors were significant for evaluating the possibilities of placing a child with a particular family. Table 1.1 summarizes the agencies’ responses.6

While there appears to have been wide variation in the matching factors considered important by the individual agencies, all the characteristics mentioned on the checklist were defined as important by at least two-thirds of the agencies. Only 10 agencies felt that it was not important to equate a child’s race to that of his prospective parent. Shapiro, the author of the study, commented:

Table 1.1

Matching Factors Adoption Agencies Considered Important

Matching Factors Adoption Agencies Considered Important

We know from practice that agencies are not placing Negro children in white homes or white children in Negro homes. Some agencies use homes for children of mixed racial background where the background of the adoptive parents is not the same as the child’s. However, in most instances the characteristics of the child are primarily white, for this kind of placement occurs more frequently with children of mixed Oriental or Indian and white background, than with children in whom the non-Caucasian blood is Negro.7

In its Standards for Adoption Service (SAS), the Child Welfare League of America (CWLA) continued to make matching a responsible part of adoption practice. In 1959, under the subtitle “Matching,” the CWLA recommended that

similarities of background or characteristics should not be a major consideration in the selection of a family, except where integration of the child into the family and his identification with them may be facilitated by likeness, as in the case of some older children or some children with distinctive physical traits, such as race.

When the age of the child and of the adoptive parents was considered, the SAS suggested that “the parents selected for a child should be within the age range usual for natural parents of a child of that age.”8

Recognizing that social and cultural attitudes are learned rather than inherited, the SAS did not recommend that these factors enter into the matching equation. The educational background of both the child’s biological family and the prospective adoptive parents was likewise minimized: “The home selected should be one in which the child will have the opportunity to develop his own capacities, and where he is not forced to meet unrealistic expectations of the adoptive parents.”9

Religion was handled in the 1959 SAS by inclusion of a rather lengthy statement representing the positions of the three major faiths:

Opportunity for religious and spiritual development of the child is essential in an adoptive home. A child should ordinarily be placed in a home where the religion of adoptive parents is the same as that of the child, unless the parents have specified that the child should or may be placed with a family of another religion. Every effort (including interagency and interstate referrals) should be made to place the child within his own faith, or that designated by his parents. If, however, such matching means that placement might never be feasible, or involves a substantial delay in placement, or placement in a less suitable home, a child’s need for a permanent family of his own requires that consideration should then be given to placing the child in a home of a different religion. For children whose religion is not known, and whose parents are not accessible, the most suitable home available should be selected.10

When dealing with physical characteristics, the SAS reiterated its overall stance toward racial matching and defined the latter as a “physical characteristic”: “Physical resemblances should not be a determining factor in the selection of a home, with the possible exception of such racial characteristics as color.”11

By 1964, the matching concept underwent a subtle but significant shift. In a CWLA publication, Viola M. Bernard made the following statement:

In the past much emphasis was placed on similarities, especially of physical appearance, as well as national, sociocultural, and ethnic backgrounds. It was thought, for example, that matching the child’s hair color, physique, and complexion to that of the adoptive parents would facilitate the desired emotional identification between them. Experience has shown, however, that couples can identify with children whose appearance and background differ markedly from their own. Instead, optimal “matching” nowadays puts more stress on other kinds of correspondencies between the child’s estimated potentialities and the parents’ personalities, values, and modes of life. Respective temperaments, for example, are taken into account. Whether similarities or differences work out better depends on many factors, which also must be considered.

Although it has been proved repeatedly that parents can identify with children of different emotional and racial backgrounds, and with all sorts of heredities, not every couple, of course, feels equally accepting of each type of “difference.” Accordingly, the child of a schizophrenic parent would not be considered for a couple who has deeply rooted fears about the inheritance of mental illness; a child of interracial background who appears predominantly white is likely to adjust best in a white family. [Emphasis added.]12

No longer were the most ostensible characteristics to be matched between child and parent. Instead, emphasis was to be placed on a child’s “estimated potentialities/’ In other words, the “unseen” instead of the “seen” was to be matched except with regard to race. Racial matching, however, continued to be stressed by the CWLA, as indicated by the following statement: “A child who appears predominantly white will ordinarily adjust best in a white family.”13

In 1968, the subtitle “Matching” was deleted from the CWLA’s SAS. In its stead appeared a category titled “Responsibility for Selection of Family.” Its wording was broad and somewhat ambiguous with regard to matching but quite clear about the role of the professional social worker and the adoption agency:

The professional social work staff of the agency (including the social worker who knows the child, the social worker who knows the adoptive family and the supervisor) should carry the responsibility for the selection of a family for a particular child on the basis of their combined knowledge about both the child and the adoptive family and the findings and recommendations of all the consultants.14

Age as a matching criterion was expanded past the 1959 statement a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Transracial Adoption: An Overview

- 2 Court Decisions Involving Transracial Adoptions

- 3 Research Design

- 4 Demographic Profiles of the Parents and Children

- 5 The Parents’ Experiences

- 6 The Children’s Experiences

- 7 How the Parents’ and Children’s Accounts Match Up

- 8 Problem Families

- 9 Ordinary Families: A Collective Portrait

- 10 The Fourth Phase

- Concluding Comments

- Selected Bibliography

- Index