- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is the first study to explore the connections between late-19th-century university/college composite class portraits and the field of eugenics – which first took hold in the United States at Harvard University. Eugenics, "Aristogenics, " Photography takes a closer look at how composite portraiture documented an idealized "reality" of the New England social-caste experience and explains how, when positioned in relation to the individual stories and portraits of members of the class, the portraits reveal points of non-conformity and rebellion with their own rhetoric.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Eugenics, 'Aristogenics', Photography by Kris Belden-Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Harvard’s “Class” Portraits: Composite Pictures and a New England “Aristogenic” Agenda

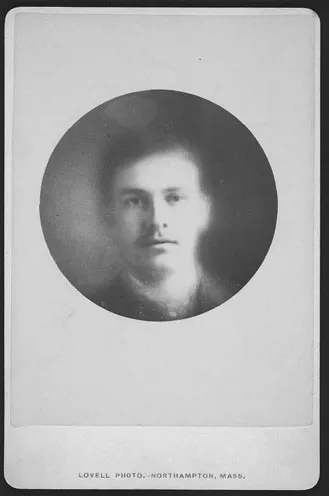

Lovell Photo’s Harvard composite class portrait of the college’s undergraduate Class of 1887 has a relatively pale face that is void of facial hair, and dark eyes that directly meet, but do not challenge, the viewer’s (Fig. 1.1).1

Figure 1.1 Charles O. Lovell/Lovell Photo, Composite of Harvard Class of ’87, 1887. Albumen composite silver print. Bowditch suggests that this composite was made from 156 portraits of the 339 graduating seniors from the Harvard College Class of 1887. Courtesy of the Harvard University Archives. Public Domain.

The subject exudes calm, quiet confidence as “his” features—none of which are too dominant or aggressive—are framed by conservatively cut dark hair and imbued with a haze that softens the young man’s narrow hairline, ears, jaw, and neck.

Despite the descriptive specificity of the portrait subject’s appearance, this composite photograph reveals the face of a young man who never existed. Instead, the image personifies the “average” outward appearance of the entire, all-male, graduating Class of 1887 at Harvard College. To make this portrait, Charles O. Lovell of Northampton, Massachusetts, carefully aligned and re-photographed dozens of portraits on a single negative to create a singular accumulated image from the multiple layers of exposures. Individual students’ facial features and bodies are obscured in a ghostly haze as they coalesce to form a data visualization, or aggregate image, of the whole group.

The Brahmin Caste of “Semi-aristocrats”: “Class” Matters

Copies of this composite photograph were sold as cabinet-card keepsakes to students and their families, and displayed/archived by Harvard College. But they also functioned as a representation of a particular social caste, Boston’s Protestant Brahmin elite, for self-celebration, self-preservation, and the affirmation of community as immigration threatened its hold on power.2 The term “Brahmin”—originally a term used to describe the highest of four social castes in Hinduism—was appropriated in 1860 by physician and essayist Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., to describe a Boston social caste of wealthy “New England aristocrats” who were “robust,” “well-bred,” and came from well-known Beacon-Hill-neighborhood families who were descended from the original Puritan American settlers.3 As such, Boston Brahmins, Holmes suggests, possessed a sense of “inherited moral responsibility,” which—combined with their Protestant beliefs, staunch Puritanical work ethic, and mental acumen—positioned them (or, the male versions of them) to be genetically predisposed to be “honorable” scholars and captains of industry.4

Holmes himself was a member of this distinguished Brahmin group. But apparently, so too were the soon-to-be-accomplished men of Harvard College’s Class of 1887, a group of aspiring professionals in respected, Brahmin-appropriate fields: 42 percent practiced law, 23 percent were in occupations they defined as “business,” 16 percent went into education fields at various levels, 12 percent were physicians, and 7 percent became bankers.5

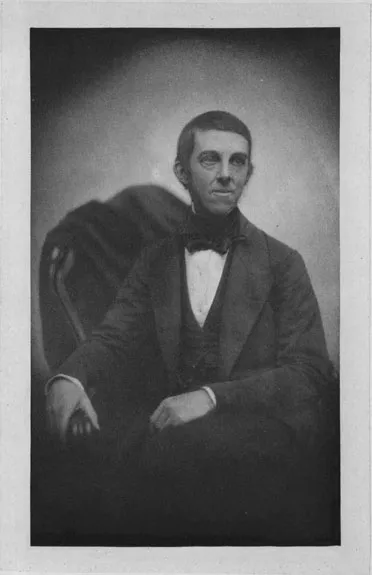

Holmes’s definition of the Boston Brahmin social caste included a description of “a distinct organization and physiognomy” that applied to young adults of the Brahmin class who attended university.6 Holmes stated: “If you will look carefully at any class of students in one of our colleges, you will have no difficulty selecting specimens.”7 A typical male Boston Brahmin university student, he argued, has “a handsome face—a little too pale, perhaps,” a narrowed jaw, light or non-existent facial hair, and a calm expression.8 As Holmes suggested, the mental image of the distinctive Boston Brahmin gentry is synonymous with the calm, focus, and dignity expected of leaders in education, culture, business, and social life.9 Holmes’s likeness, captured around 1860, exemplifies this description (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Photographer unknown, Portrait of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., 1860. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, olvwork594981. Public Domain.

A clean-shaven, well-dressed, dignified, Holmes sits with his hands folded in his lap and meets the viewer’s gaze with a soft, non-confrontational expression. Holmes’s face is narrow, fair in complexion, and wears a calm expression. He is a self-composed and poised exemplar of the Brahmin ideal. Likewise, Lovell’s Harvard Class of 1887 composite is fair-skinned and also wears a calm, non-confrontational expression exemplary of Holmes’s definition of the Boston Brahmin.10 Such young men, after all, were likely to be heirs to roles in industry leadership—positions that required and rewarded sharp-thinkers who could remain stoic and rational in a crisis.

In a letter to eugenics movement founder/Englishman/friend Francis Galton, US eugenicist/physiology professor/Harvard Medical School dean Henry Pickering Bowditch marveled at how these composites showed a “talented” class of Americans who were “singularly interesting” and possessed “beautiful faces!”11 The “softness” of their eyes, Bowditch wrote, told of their increased intellectual capacity, and their firm-but-not-overwhelming brow lines indicated a tempered degree of vigor.12 Bowditch featured the Harvard College Class of 1887 composite in the second row (third from left) of his publication for the 1921 Second International Exhibition of Eugenics, as proof of the potential gains of positive eugenics, which celebrated the merits of breeding only among people of superior genetic lines (see Fig. 0.4).

Other representations of the Boston Brahmin from the nineteenth century concur with Holmes’s description. In an essay about Boston businessman and politician Martin Brimmer, whom Harvard-educated author and essayist John Jay Chapman considered “The Perfect Brahmin,” Chapman remarks: “He was a lame, frail man, with fortune and position; and one felt that he had been a lame, frail boy, lonely, cultivated, and nursing an ideal of romantic honor.”13 Brimmer also, according to Chapman, was active in “philanthropy, art and social life,” and he was socially adept: “I might gambol or even wallow, but he would blossom in the perfection of self-effacing courtesy.”14 Thus, “The Perfect Brahmin” was self-deprecating, culturally well-versed, honorable, charming, social, highly educated, modest, and was born with a degree of privilege that opened doors to the potential for great accomplishments. Physically, he was not overly dominant or commanding, but instead exuded the dignity and refinement telling of his class.

As Holmes’s and Chapman’s comments suggest, many quietly proud Boston Brahmins themselves felt their bloodline was superior to those of other immigrants, despite its tendency to be less physically robust. Literary scholar Bluford Adams has argued that the New England Anglo-Saxons from whom the Brahmins originated even saw themselves as “better” than their European ancestors because the New Englanders also shared a lineage with the Puritans, who were deemed “a vigorous and good stock.”15 The successful work of building new settlements in New England, which required self-organization, dedication, courage, creativity, and fortitude, Adams suggests, “enhanced the racial characteristics of their ancestors, turning them into the finest members of their race—the most pure-blooded, independent, inventive, and self-governing Anglo-Saxons—but just in America but on earth.”16

Under Brahmin economic and industrial leadership, and with the benefit of that caste’s monetary support, Boston grew into a center of cultivated culture after the US Civil War. Boston was called the “Athens of America” and the “literary capital of America” during the 1880s, and was an important educational, artistic, social, and cultural hub throughout the nineteenth century.17 In fact, the only thing better than being a (male) Boston Brahmin, according to an essay by an anonymous and envious writer from The Kansas City Times, dated January 17, 1887, was to enjoy the ultimate privilege of being a (male) “Cambridge Brahmin,” who was tightly bound to not only the culture of Boston, but enjoyed easy access to the sub-cultures encouraged by Harvard: “The Boston Brahmin is a superior being and he is fearfully and wonderfully made. Still, he is exceeded by one other type—the Cambridge Brahmin, who, indeed hath all things under his feet.”18 This is to say, a Harvard graduate was the most desired and most privileged type of individual in the country.

But the arrival of Irish immigrants challenged Brahmin political power and influence in the late nineteenth century.19 Boston elected its first Irish Catholic mayor, Hugh O’Brien, in 1889. Before holding that office, O’Brien—who emigrated from his native Ireland to the US in the 1830s—served as a Boston alderman starting in 1875. Brahmins fearfully noted that these new immigrants may have been poor, but they also were politically well-organized, and far more numerous than their caste. Seeing one significant vein of Brahmin power threatened, the caste fought back by encouraging positive eugenics to repopulate its gentry, drafting and supporting anti-immigration policies, founding and leading anti-immigration organizations, and negative eugenics to discourage the “bad breeding” of the “Other.” ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Harvard’s “Class” Portraits: Composite Pictures and a New England “Aristogenic” Agenda

- 2 A “Dandy” Masculinity? Establishing and Respecting Cisgender Norms, Using Photography

- 3 Social Poise and Demure Confidence: Swaying the College Women to be the Essential Players in Positive Eugenics

- 4 Biometrics and Posture Pictures: “We Did What We Were Told”

- Conclusions

- Index