- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Uzbekistan’s International Relations

About this book

This book examines the development of Uzbekistan's international relations since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Uzbekistan’s International Relations by Oybek Madiyev in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Uzbekistan’s relations with major powers

To whatever degree we may imagine a man to be exempt from the influence of the external world, we never get a conception of freedom in space. Every human action is inevitably conditioned by what surrounds him and by his own body.

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

Introduction

In the 1990s, there was an expectation that Uzbekistan, along with other countries in Central Asia, would gradually move towards the West, both economically and politically, by distancing itself from the sphere of Russian influence. This expectation was given further impetus by both domestic and foreign policy actions of the government of Uzbekistan, e.g., switching from the Cyrillic alphabet (which was introduced under Joseph Stalin in 1940) to the Latin script (1992), ending the Rouble as the legal tender in the country (1993), officially taking the Russian TV channels off air (1994), withdrawing from the CIS Collective Security Treaty (1999), officially becoming a member of GUAM (Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova, an organisation supported by the US as a way of countering the Russian influence in the area) at a ceremony at the Uzbek Embassy in Washington, making it GUUAM (1999) and allowing the US to station its airbase on Uzbek soil (2001).

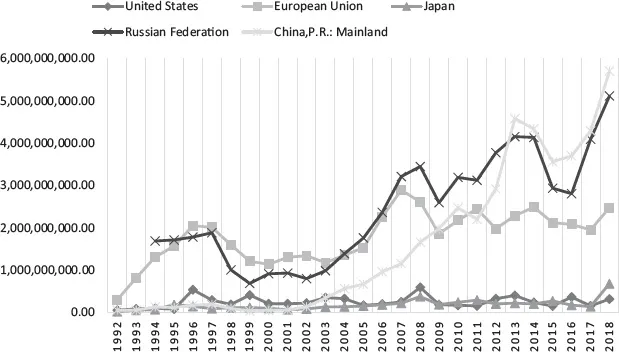

Moreover, Islam Karimov, the then President of Uzbekistan, in his several books published in the 1990s,1 recalibrated the new Uzbek foreign policy strategy as a political and economic shift towards the West, in particular the US, the EU and Japan. Karimov characterised this approached oriented towards the ‘developed West’ as the government’s highest foreign policy priority which aims to attract Western capital, investment and businesses and establish a strategic (long-term) partnership with them in order to achieve economic development. Based on this foreign policy vision, Uzbekistan’s relations with China was barely mentioned and cooperation with Russia was only limited to the CIS framework, the block which he criticised as a tool for Russia to regain its chauvinistic dominance in the post-Soviet sphere.2 Karimov also criticised Russia’s behaviour as an ‘attempt to restrict Uzbekistan’s external economic linkages and impose its own unequal character … through neo-colonialist and neo-imperial approaches’.3 However, in spite of this and the West’s own significant investments in Uzbekistan’s national economy, and its attempt to enter the Uzbek market (through both bilateral and multilateral channels),4 this shift never materialised. In fact, as the figures show (see Figures 1.1 and 3.1), since the collapse of the Soviet Union Uzbekistan’s trade cooperation with Russia has remained robust and only in 2014 China overtook Russia as Uzbekistan’s and the region’s biggest economic partner, mainly in trade, investment and economic aid. Since then China has been keeping pace with Russia for its strategic engagement with Central Asia and wider Eurasia.

This book will explore why Russia and China have been more successful in establishing economic cooperation with post-Soviet Uzbekistan than the West’s major powers. Although the book will reflect on the recent domestic and foreign policy changes in Uzbekistan since the end of 2016, the book’s analysis largely focuses on understanding the Karimov era policy-making and Uzbekistan’s interaction with international actors.

The book will explore the following key interrelated questions: Why do Russia and China win this so called ‘Great Power’ game? What were the Chinese competitive strategies to shift its attention towards Uzbekistan? What is the role of SCO in China’s expanding trade relations with Uzbekistan? How does the Uzbek regime choose its partners with which to cooperate? How does domestic politics contribute to shaping Uzbekistan’s international engagement? How do we understand Uzbekistan’s own post-Soviet foreign economic policy and its decision making? What is the role of domestic socio-economic and socio-political structure in Uzbekistan’s engagement with major powers? Will the recent political, economic and social changes in Uzbekistan, since Mirziyoyev became president in 2016, make the government to play in multiple international cooperation directions?

Figure 1.1 Uzbekistan and the Major Powers: total trade, 1992–2019 (value US$)

Source: Data collected from the International Monetary Fund. Directorate of Trade Statistics Yearbook. 1992–2019

In order to answer these questions, it is important to start by outlining the main domestic and international factors and their interaction. First of all, there are international factors: globalisation the rise of China and increase in global demand for natural resources; the role of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), designed to enhance security and economic cooperation, focusing on ‘trade, investment, transportation, energy’ policies and the Silk Road Economic Belt; and Russia’s attempt to reclaim its ‘Great Power’ status since 2000 and President Putin’s attempt to build and expand the Eurasian Economic Union. There are also factors like geopolitical struggle for post-Soviet regional dominance.

Second, there are domestic factors: understanding the specific patterns of the configuration of Uzbekistan’s state and its choice of post-Soviet political economy. Why have Uzbekistan’s leaders adopted a Chinese-style gradualist model, while ignoring the ‘Washington Consensus’? Among the explanatory pattern there is the importance of analysing not only economic and political but also social and cultural factors, notably the structure of Uzbek society and its relationship with the government in a historical perspective. This, I will argue, is linked with the historical development of its state-society relations. We also need to understand Russia’s and China’s foreign trade policy linked not only with economic growth but also with the structure of foreign economic policy decision making, or ‘power vertical’, among other domestic elements. My argument is that unlike the Western liberal democracies, the nature of the Uzbek government and its society is more ‘naturally’ inclined to establishing trade networks with the states like China and Russia, as Uzbekistan lacks autonomous and robust institutions, independent layers of society which help to keep the government’s domestic and foreign policy accountable and at the same time provide resistance to various external force influences. The consolidation of power is vertical rather than horizontal.

This case is relatively new within both International Relations (IR) and International Political Economy (IPE), as Uzbekistan, as well as the region of Central Asia as a whole, has been understudied in these disciplines in spite of being historically at the heart of rivalry among the ‘Great Powers’ such as Britain and Russia. The issue of Uzbekistan’s post-Soviet political economy and the role of external powers provide particularly interesting case with its distinct traits and characteristics.

In this sense, this research will help to develop and contribute to a different type of IR and IPE explanation, which is more sensitive to the particular role of the powers like Russia and China in this contemporary system of global political economy. The research will also contribute to the study of the increasing geopolitical and geo-economic significance of the Central Asian region itself that has previously been overlooked within the context of IR and IPE. It will also contribute to general literature of the study of post-communist states. Overall, the research is also very timely as it coincides with a great deal of public debate regarding aid and trade, energy security, energy resources and democracy, world nuclear energy concerns and the rise of China.

Why Uzbekistan? The significance of studying Uzbekistan’s cooperation with major powers

Uzbekistan emerged as an independent country after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, ending more than a century of the Russian rule. The population of Uzbekistan is over 33 million, the most populous county in Central Asia, the third largest among the CIS countries (after Russia and Ukraine) and 41st in the world.5 This country is rich in natural and mineral resources. Its economy mainly relies on exporting commodities, including energy products, cotton, gold, mineral fertilisers, ferrous and non-ferrous metals, textiles, food products, machinery and automobiles.6 Uzbekistan has the fourth largest gold deposits in the world. The country mines more than 80 tonnes of gold annually, seventh in the world.7 Uzbekistan’s copper deposits rank tenth in the world. It has the world’s seventeenth largest gas reserves. It ranks eleventh in the world in natural gas production with an annual output of 60 to 70 billion cubic metres, the third in Eurasia, behind Russia and Turkmenistan. It is also home to considerable uranium reserves. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) ranks Uzbekistan as seventh in the world for uranium reserves, fifth for extraction and third for export.8 It is the fifth largest producer and the second largest exporter of cotton in the world.9

From a geopolitical point of view, Uzbekistan, one of the two double landlocked countries in the word, is located in the middle of Central Asia, which is surrounded by the major powers of Russia and China (see Map 1.1) and vulnerable to the impact of instability in neighbouring areas – including the Middle East, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The fall of the Soviet Union, the rise of China and the stationing of the US military forces after 9/11 led to a constantly changing balance of power in the region. Central Asia is also a region of largely untapped natural mineral resources. These resources have become increasingly desirable as world supplies are depleted and political unrest in the Middle East leads the developed world to look for other sources. This has meant that the region has become one of the last areas of continued competition among the world’s major economic powers. Most scholars on Central Asia refer to this competition as the ‘New Great Game’,10 arguing that it is becoming increasingly important for the world’s major powers to have some stake in Uzbekistan and the region of Central Asia as a whole and linking it with Harold Mackinder’s classical work on the pivot of history, known as heartland theory.11 Rudyard Kipling had originally coined the term ‘Great Game’ in his book Kim when referring to rivalry in Central Asia between Britain and Tsarist Russia in the nineteenth century. According to Cooley, the ‘Great Game’ metaphor is ‘appealing precisely because it suggests that great powers still attempt to sway, coerce, persuade and buy the loyalties of strategically vital governments, while blocking their rivals from doing the same. This is the stuff of geopolitics of the highest order’.12

Map 1.1 Central Asia

Analytical framework: (neo-)Gramscian IPE, and exploring Uzbekistan and major power dynamics in the wider regions

The so-called ‘New Great Game’ literature in IR since the 1990s grew from within the Realist tradition, which focuses on the strategic interests on the major powers in the world and argues about complexities that ‘facilitate bandwagoning, balancing and buck-passing as strategic response to maximise interests and constrain internal and external actors in any given region from realising hegemony’.13 The main contributions accentuate the goals, actions and intentions of the US, China and Russia in Central Asia. They offer almost single predictable and repetitive forms of motion.14 The problem with this type of IR explanation is that it gives too much emphasis on the ‘hegemonic’ position or behaviour of the major powers in Uzbekistan and, as a consequence, has neglected those areas of Uzbek foreign policy more likely to be determined by domestic political, economic and social influences. Moreover, in spite of some important attempts in recent literature15 to argue that Uzbekistan has exercised a considerable degree of agency over the years, most IR Great Game texts still give impression that Uzbekistan is a peripheral actor. This has happened largely because they focus almost exclusively on ‘high’ politics, linking issues with neo-imperialism and interest of the major powers.

Domestic or Comparative Political Economy (CPE) texts, which elaborate Uzbekistan’s post-Soviet political economy provide a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of maps

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Uzbekistan’s relations with major powers

- 2 Rethinking state-society relations in Uzbekistan

- 3 Russia in Uzbekistan

- 4 China in Uzbekistan

- 5 The United States in Uzbekistan

- 6 Other major powers: Japan and the European Union in Uzbekistan

- 7 Conclusion

- Index