The dominant form of law-making is legislation. The process is covered in the Guide to Making Legislation issued by the Cabinet Office.1 The parliamentary stages are treated in much greater detail in Erskine May, Parliamentary Practice, 25th edn (Butterworths, 2019) 1,281pp. (Erskine May, the authoritative guide to parliamentary practice and procedure, was first published in 1844. In July 2019 it became available online free to all.)

In recent decades, while the number of Acts passed by the UK Parliament declined, the number of pages per Act increased. In the 1970s, 73 Acts were passed each session on average, falling to 62 in the 1980s, 54 in the 1990s, 47 in the 2000s. There was then a small rise to 49 Acts each year in the 2010s. Whilst there was an average of 16 pages per Act from 1930 to 1950, this rose to 21 (1950–80), 33 (1980–90), 46 (1990–2000), to reach 85 (2000–2010).2 The House of Lords Constitution Committee suggested that one reason for the increase in length of statutes was a difference in formatting.3 The Institute for Government found that legislation passed between 2007 and 2015 typically grew in length by around 40 per cent due to amendments made during the bill’s passage through both houses.4

Legislation takes the form either of Public or Private Bills. Most Acts are Public General Acts that affect the whole public. Private Acts are for the particular benefit of some person or body of persons such as an individual or company, or local people. They must not be confused with Private Members’ Bills – for which see 2.1.7 below. Private Acts sometimes deal with the affairs of local authorities and are then called Local Acts. To confuse matters, Local Acts are sometimes the result of Public Bills but any Public Bill which affects a particular private interest in a manner different from that of other similar private interests is technically called a Hybrid Bill (see 2.1.6 below). The significance of the difference between Public Bills, Private Bills and Hybrid Bills lies in the parliamentary procedure adopted in each case. This book concerns itself primarily with Public Bills.

In addition to Acts of Parliament there are also very large numbers of statutory instruments (SIs; see 2.17–2.19 below). In the early years of this century the number of statutory instruments was in the hundreds; since the Second World War it has been in the thousands, and again the number of pages has been increasing greatly. In 1951 there were 2,335 new statutory instruments running to 3,523 pages. Fifty years later, in 2001, there were 4,150 SIs running to 10,760 pages. In the 2010s to June 2019 SIs averaged around 3,000 per year and an average length of 6 pages.5

1.1.1.The Sources of Legislation

The belief that most government bills derive from its manifesto commitments is mistaken. There is no recent research but only 8 per cent of the Conservative government’s bills in the period from 1970 to 1974 came from election commitments and in the 1974–79 period of a Labour government the proportion was only a little higher at 13 per cent.6 The great majority of bills originated within government departments, with the remainder being mainly responses to particular and unexpected events such as the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act 1974 in response to the Birmingham IRA bombings, or the Drought Act 1976.

A considerable number of bills derive from the recommendations of independent advisory commissions or committees. Some of these are ad hoc – such as Royal Commissions, Departmental and Inter-Departmental Committees. Others are standing bodies, notably the Law Commission.7 Research on twenty-five years of legislation showed that as many as a quarter to a third of all statutes that could have been preceded by the report of an independent advisory committee or commission were the result of such a report. Dr Helen Beynon studied all the Public Bills that received Royal Assent between 1951 and 1975 (a total of 1,712 statutes). She excluded from the study various categories: (1) legislation that did not change the law, such as consolidation or statute law revision legislation, or re-enactment legislation; (2) emergency legislation rushed through to deal with some unexpected crisis; (3) certain financial legislation such as the Appropriation Acts which authorise the bulk of annual expenditure and Consolidated Fund Acts authorising interim and supplementary expenditure; (4) legislation concerning the Civil List which pays for the monarchy; and (5) statutes to give effect to treaties and other international commitments. When these were eliminated, there remained 1,335 statutes. In no less than 380 cases (28%) the statute was preceded by a report of an independent advisory committee or commission.8

Very little has been written about the process of preparing legislation as seen from Whitehall’s perspective. A rare instance, however, was a paper by a senior Home Office official speaking at a Cambridge conference on penal policy-making in December 1976. (In those days, unlike the present era, penal policy was not a hot party political issue.) The paper is based on work done several decades ago but it gives an idea of the wide range of influences that often lies behind a major piece of legislation. That will be as true today as then.

Michael Moriarty, ‘The policy-making process: how it is seen from the Home Office’ in Nigel Walker (ed), Penal Policy-Making in England, Cropwood Conference (University of Cambridge, Institute of Criminology, 1977) 132–39.

In general it is unusual for an incoming government to bring with it anything approaching a detailed blueprint of penal policy …

The absence, usually, of a strong and detailed Party programme on penal matters does not mean that an incoming Home Secretary (or other Home Office Minister) may not have its own well-formed objectives and priorities. A recent example is the Ministerial commitment, since March 1974, to improving bail procedures and developing the parole system. But time and again the Ministerial contribution to penal policy-making, at least as it appears to the observer and participant within the Home Office, lies not in the Minister’s bringing in his own fresh policy ideas, but in his operating creatively and with political drive upon ideas, proposals, reports etc, that are, so to speak, already to hand, often within the department but sometimes in the surrounding world of penal thought.

Sources of the Criminal Justice Act 1972

The year 1970 was notable for a sharp rise in the prison population to what was then a peak of 40,000,9 which gave rise to intensified policy discussions within the Department of ways of developing alternative measures. The Report of the Advisory Council on the Penal System (ACPS) on Non-Custodial Measures (the ‘Wootton Report’)10 contained a number of relevant proposals, notably a proposal that offenders should carry out community service. The Department instituted an urgent study of the practicalities by a working group with substantial probation service representation. Two other working groups were set up at the same time: one on use of probation resources, the other on residential accommodation for offenders. The main production of the first of these was a proposal to establish experimentally some day training centres, on a model originating in the United States, interest in which had been stimulated by the Howard League for Penal Reform among others. The other group developed ideas for running probation hostels: a substantial adult hostel building programme was established in 1971, following a small-scale experiment promoted by the Department in extending this method of treatment to those over 21. Detailed work on the proposals in the ACPS report on Reparation – the ‘Widgery Report’11 – was also going on.

Thus the Criminal Justice Bill of 1971/2 could be said to be born from a fusion of a Ministerial desire to be active in the criminal justice field, along lines which were identified but not too rigidly pre-determined by them, with a supply of departmental and other raw material that was lying ready or in process of being worked up. Much of the Widgery Report was in tune with a political objective that offenders should recompense their victims. From the Wootton Report, the community service proposal appealed partly for its reparatory element, partly because it was a non-custodial penal measure (Ministers were already well aware of the need to try to bring down the prison population) that would appeal to those who were suspicious of ‘softness’. The form in which the community service proposals appeared in the Bill owed something to the specific intention of Ministers that the new measure should be seen as a credible alternative to custodial sentences.

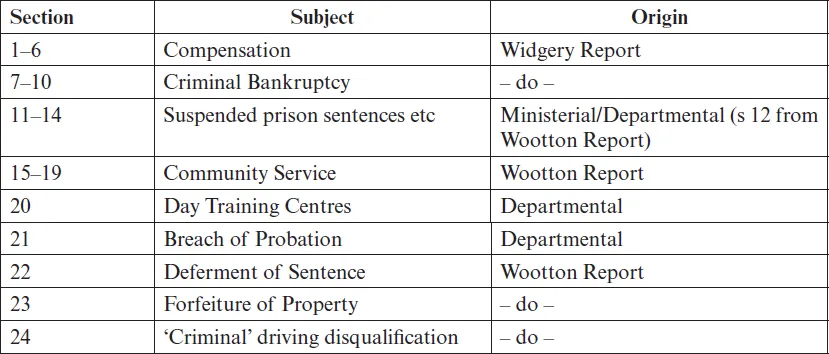

In fact recommendations from the two ACPS reports made up much of the ‘core’ of the Bill – Part I entitled ‘Powers for Dealing with Offenders’. In the form in which it received Royal Assent, Part I comprised 24 sections (and one linked Schedule) which related to the main sources of the Bill roughly as … [indicated in Table 1.1]:

Table 1.1 Sources for the Criminal Justice Bill 1972

Not all the sections listed … [in Table 1.1] were in the original ‘core’: the origin of some of the later starters is illustrative of how penal policy is formed. What became section 14, extending the principle of the First Offenders Act to a wider range of adult offenders, was devised during the preparatory stage as a counter-weight to the ending of mandatory suspension of sentence. Other provisions owed their origin, or final form, to the Parliamentary proceedings on the Bill.

However, the bulk of the Bill was devoted to provisions aptly described as Miscellaneous and Administrative Provisions (sections 28 to 62). Some of these supported Part 1 provisions (eg administrative aspects of community service) or were otherwise related to its main themes (eg probation hostel provision; legal aid before first prison sentence). Others covered a wide range of topics of varying importance. In source they were hardly less diverse. At least one – increase in penalties for firearms offences – was a ‘core provision’; some came from organisations close to the Home Office such as the Justices’ Clerks. The provision giving ‘cover’ for the police to take drunks to a detoxification centre (section 34) had its origin in the report of the Working Party on Habitual Drunken Offenders.12 Others came from the famous pigeon holes of Whitehall – and these in turn can be sub-divided into, on the one hand, tidying up and, on the other, more substantial though minor changes – for example simplification of parole procedure (section 35).

… In 1970–1 much detailed work was done on community service and criminal bankruptcy in particular, but to a lesser degree on the other major Bill proposals in working parties by the Home Office which brought into consultation others whose advice and co-operation were needed. The community service working group included representatives of the probation service, magistracy and voluntary service movement; the criminal bankruptcy group included lawyers of both the Home Office and Lord Chancellor’s Office and officials from the Bankruptcy Inspectorate of the (then) Board of Trade.

Beyond this area of activity there was (to move on to a second point) a wider and continuing process of consultation, on particular proposals and on ways of giving effect to them, with many official and non-official interests. A number of Bill proposals affected other Government departments – for instance, Transport and Health and Social Security – in addition to those already mentioned. On any penal policy it is necessary to keep the Scottish and Northern Ireland Offices in close touch. The Director of Public Prosecutions was closely involved in the criminal bankruptcy scheme and other Bill matters, at least one of which owed much to his suggestion. Consultation also went on with the police and probation services (the prison service was not greatly affected by the Bill, except as a hopeful beneficiary), the judiciary, magistrates and justices’ clerks. The various representative organisations of course play an active part in the consultation process; and the burden on them can be a heavy one, especially as the pace quickens. The task of keeping the consultation process on the move while doing all the other preparatory work also makes considerable demands on the small team of officials working on a Bill.

In a more recent study, Professor Edward Page of the London School of Economics, examined the role of civil servants in the legislative process, a subject on which there had been a signal dearth of knowledge and writing.13 The study was an investigation, through interviews with civil servants, of four bills that became Acts in 2002: The Employment Bill (‘Employment’), the Adoption and Children Bill (‘Adoption’); the Proceeds of Crime Bill (‘Crime’); and the Land Registration Bill (‘Land’).

In each case there was a manifesto pledge covering significant portions of the bill but Page says that in each case the manifesto commitment ‘resulted to a great or lesser degree from the ongoing Whitehall process’ (Page (n 16) 656). In two of the four cases – the Crime and Land bills – civil servants who served on the eventual bill team played a pivotal role in placing items on the political agenda and seeking to make sure that the government committed itself to legislation. With land registration, the subject had been under discussion since the 1960s but it was a particular individual (Charles Harpum, who became a Law Commissioner in 1994) who caused a viable proposal for major reform to emerge through collaboration between the Law Commission and the Land Registry. Two members of the eventual departmental bill team were involved in the Law Commission/Land Registry working party. In the case of the Crime Bill, ‘the activism of officials created proposals for change which the government later accepted’ (Page (n 16) 657). Three of the Home Office officials who were on the 1998 Working Group on Confiscation, on whose Third Report the legislation was based, were members of the later...