![]()

1

Introduction

What seemed completely impossible before – in a no-man’s-land to where only exiles were banished in tsarist times – now, by the will of the Bolsheviks and based on the half-tundra’s natural riches, where no human had until recently set foot, a new and rapidly growing industrial center along the Arctic Circle has been created.

Sergei Mironovich Kirov, 19341

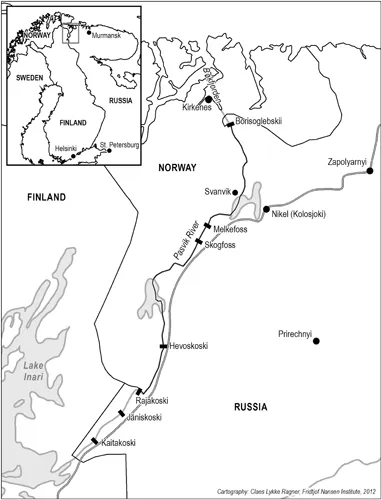

To the far north of Europe, well above the Arctic Circle, in the northwestern corner of the Russian county (oblast) of Murmansk on the Kola Peninsula, we find the municipality (raion) of Pechenga. Neighbour to the Norwegian county of Finnmark to the west, and Finnish Lapland to the southwest, Pechenga’s landmass stretches along the eastern banks of the Pasvik River (Reka Paz in Russian; Paatsjoki in Finnish),2 which forms most of the border between Russia and Norway. The Pasvik River flows from the vast Lake Inari in Finnish Lapland to the northeastern section of the Atlantic Ocean – the Barents Sea. It provides energy to no less than seven hydroelectric power plants, two Norwegian and five Russian, along its 145-kilometre course (see Map 1). Most of the electricity produced here is consumed by the local power-intensive nickel industry in the valley, the Pechenganikel combine. With its undulating hills and abundant wildlife, the area can at first glance seem like one of the quietest corners of Europe. Its history, as will be demonstrated in this book, suggests otherwise.

Map 1 The Pasvik valley and surroundings.

In this book the Pechenga territory, whose fate has been intertwined with the local industrial activity, is at the centre of attention. Throughout the investigation, albeit with varying emphasis, the dynamics and interaction between commercial ambitions and state security will be highlighted. Specifically, I analyse Soviet security concerns and economic thinking as these became evident in Pechenga. With this study, I intend to contribute towards contextualizing today’s political and academic hyperbole surrounding Arctic regions: the Arctic has a past, and Pechenga was one of the places in the European north where security and economic interests were not only balanced against each other but forged. Only through a deep understanding of the dynamic history of places like Pechenga can the Arctic of today truly be understood.

The present study will also inform our knowledge about wider historical processes. While Pechenga and its nickel resource figure as the sole constant in the narrative, its development touches on a range of high-impact historical events: this book will shed light on Soviet–Finnish relations after the Russian Revolution, Soviet motives and strategies before and during the Second World War and the nature of the Stalinist economy in the first post-war years. While having no pretensions of (re)interpreting all these widely studied historical phenomena, I hope this book will provide some new insights pertaining to them.

The significance of Petsamo

Petsamo, as Pechenga was called while under Finnish sovereignty from 1920 to 1944, was not merely a piece of real estate. It represented much more. Firstly, and most importantly, the ice-free Petsamo fjord gave Finland access to the world oceans, thus rendering the country’s dependence on passage through the Danish straits in the Baltic Sea less crucial. The Petsamo route did prove itself extremely important in periods of high tension, most notably from May 1940 to June 1941, when Sweden and Finland’s only access to world markets went through the port of Liinahamari. In this period, Petsamo also provided an outlet for Jewish refugees. More prosaically, Finland’s traditional fisheries in the Barents Sea were bolstered through national control over a section of the Arctic coastline, and in the latter part of Finnish sovereignty, the area was being developed as a tourist destination.3

But it is the industrial aspect of Petsamo that will be this book’s main concern. Quite soon after gaining possession of the territory, Finnish authorities set about mapping its geology. As we shall see in Chapter 2, a rich vein of nickel ore was discovered and would gradually be developed for industrial purposes. I will throughout this book argue that it was this geological feature that would be at the forefront when Petsamo’s destiny was shaped by several interested parties, such as the Finnish state, Canadian and German industrialists, the German Wehrmacht and the Soviet government. It was to a large degree the local resource, nickel ore, that attracted non-Finnish actors to the area and turned it into not only an industrial asset, but also a political bargaining chip for the Finnish government to make use of in its never-ending quest for security. The main reason for this international preoccupation with Finnish nickel lay in the ore’s application: Nickel is counted among the ‘strategic metals’, as it has since the late 1800s been a pivotal ingredient in war important war materiel, most notably ammunition and armoured plates.

The nickel in Petsamo was from the mid-1930s a constant in Helsinki’s foreign and trade policies. Prolonged negotiations with various industrial actors over its development took place. The nickel resource was not only to be exploited in and of itself, but also made to contribute towards the welfare of the Finnish population. The Finnish government always kept a keen eye on factors such as employment for the northern workforce in these negotiations, obviously in addition to demanding taxation arrangements that would bolster their coffers. Crucially, Helsinki only leased the concession rights, but preserved Finnish ownership over the land.

As the world progressed towards conflict in the latter years of the decade, security concerns became an increasingly important aspect of the Petsamo property. A repository of a strategic metal, the area now became an object of German and Soviet desires. As such, it could be – and was – used as an element in Finland’s self-defence against the soon-to-be warring powers. This self-preservation, combined with aspirations for territorial advances in the east, led Finland to side with Europe’s main aggressor Germany in the upcoming Great-Power struggle.4 What did Hitler gain from the arrangement? Of course, Finland constituted the northern flank in his megalomaniac Barbarossa plan, but there was also the Petsamo nickel, a resource he himself described several times as pivotal for the German war industry.

At that time, the Soviet approach to Petsamo had already developed from seemingly disinterested to aggressively pursuant. The underlying shift in Moscow’s assessment of Petsamo, the reasons of which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3, came suddenly and surprisingly to Finland in June 1940. After that, the Soviet desire to annex the area to the socialist realm never abated. Towards the end of the war, as Finland capitulated and agreed to shed its brotherhood in arms with the Nazi forces, Petsamo was no longer Finnish, but became Soviet Pechenga.

Thus, the area entered into a new phase in its dramatic history, which gives us an opportunity to study how the local industry fared in a production system alien to the one in which it had first been established, namely the Soviet planned economy. As part of the socialist homeland, this former Canadian property would be ‘Sovietized’. By this is meant a process different to the political upheaval experienced in Eastern European countries, the so-called People’s Democracies, at the end of the Second World War. Instead, Pechenga and its nickel industry, now a part of the Soviet Union, was organizationally and economically transformed to become an integral part of the Soviet production system.

Studying this period in Pechenga’s history, which was heavily influenced by the fervent rebuilding effort during Stalin’s fourth five-year-plan (1946–50), will render insight into the inner workings of Soviet industrial production and the everyday life of administrators and factory workers in Soviet enterprises. Ultimately, we will study the means by which the socialist state attempted to accomplish the grand economic expansion that would by design bring it up to par with, and eventually past, Western capitalism. In other words – Chapter 4 provides a regional history of late Stalinism.

But Pechenga was still not brought to complete Soviet isolation. Yet another period of international engagement in the area, this time by Finnish and later Norwegian hydropower specialists and construction workers, would soon commence. The first hydropower station on the Pasvik River was partly rebuilt, partly constructed by the Finnish firm Imatran Voima on a patch of land that until early February 1947 was still Finnish property. However, through shrewd combined negotiations on various fronts, Soviet representatives were able to not only acquire even more Finnish territory, but also have the main power supply to Pechenga’s nickel industry built by Finnish hands – for free, so to speak.

In Chapter 5, we will follow this process towards the completion of the Jäniskoski hydropower plant in 1951. This entrepreneurial venture, which involved Soviet industrialists getting to grips with reality in capitalist Finland, constituted at times a veritable clash of cultures. Interestingly, however, the story also illustrates how shared ambition across the political divide could trump ideological inhibitions. The main protagonist of the chapter, Boris Mefodievich Kleshko, can serve as the embodiment of the apolitical industrious spirit, result-driven ambition and personal brilliance that even the immense bureaucratic hurdles posed by the Stalinist system and the same system’s widespread infighting could not quite quench.

Following its inclusion in the Soviet realm in 1944, the Pechenga nickel industry underwent a profound transformation. The privately owned industrial operation, severely damaged after the war, was hastily rebuilt and reinvented as a Soviet enterprise. To provide the context for discussing Soviet strategic and industrial thinking of that time, and how the then Finnish–Soviet border territory figured in it, we will in the following examine several aspects of the Stalinist system that turned Finnish Petsamo into Soviet Pechenga. The insights presented here will be revisited and discussed on the basis of the intervening chapters in the concluding chapter of the book.

Settling of the Soviet North, and Stalinist totalitarianism

The 1930s are a thoroughly examined period in Soviet history. With Stalin at the height of his powers, it was the decade of such brutal historical processes as forced collectivization, involving the completion of the ruthless de-kulakization campaign (raskulachivanie) that had started in the late 1920s, the political transformation and unifying of Soviet cultural life and later the Great Terror. Another aspect of Stalin’s staggering ‘revolution from above’5 was the expansion of the industrial resource base, prompting the exploration and subsequent incorporation of the Soviet Arctic into the socialist production system. This highly romanticized ‘settling of the North’ (osvoenie severa) was in a way the Soviet response to American pioneers’ westward push to the Pacific coast in the 1800s. In the spirit of the words uttered by Leningrad Party boss Sergei Kirov – ‘there is no land that Soviet power cannot transform for the good of mankind’ – the resources of the North were to be explored and exploited for the benefit of the Soviet fatherland.6 Of course, the Soviet North was by no means settled solely by willing and enthusiastic pioneers; among the many hands that unearthed precious metals such as nickel were prisoners within the system of correctional labour camps (GULag).7

The Kola Peninsula, with most of its territory north of the Arctic Circle, was among the targets for Soviet pioneering. Striving for resource autarchy, the Stalin regime began eagerly mapping the mineral riches in these northwestern outskirts. Throughout the 1930s, the region was industrialized on a massive scale.8 When Petsamo (from then on Pechenga) was annexed by the Soviet Union in the fall of 1944, the previously Finnish territory was therefore a logical appendix to an already substantial industrial expansion. However, the industrial capacities on the Kola Peninsula had, like the nickel industry in Petsamo/Pechenga, been severely damaged during the war. Also, the unity of the wartime alliance gave way to increasing animosity between former co-belligerents. The Soviet Union spared nothing in its attempts to overtake the West. There ensued a period not only of recovery, but of frantically trying to catch up with ideological foes in the West.9 The Pechenganikel combine, as the formerly Canadian-owned nickel industry was called as a Soviet state enterprise, was hastily enlisted among the industrial entities that were to contribute to this effort.

Preoccupied with fervent industrial production and ideological competition, the Soviet post-war rebuilding efforts were in many ways reminiscent of the large-scale industrialization that had started some fifteen years earlier. In his groundbreaking study of Stalinist civilization as expressed through the early history of the steel-producing company town Magnitogorsk in the southern Urals, Stephen Kotkin describes those times as follows:

In the 1930s, the people of the USSR were engaged in a grand historical endeavor called building socialism. This violent upheaval, which began with the suppression of capitalism, amounted to a collective search for socialism in housing, urban form, popular culture, the economy, management, population migration, social structure, politics, values, and just about everything else one could think of, from styles of dress to modes of reasoning. Within a steadfast but vague noncapitalist orientation, much remained to be discovered and settled.10

In Kotkin’s interpretation, these values, however distorted they became, constituted the foundation for the Stalinist civilization of which Magnitogorsk was a prime example.

Kotkin’s in-dep...