![]()

I

THE WORLD OF THE BOOK

![]()

1

A Marketplace for Religious Ideas

ON NOVEMBER 24, 1710, Bernard Picart joined a group of friends in The Hague for a meeting of what they called the general chapter of the Knights of Jubilation. At first glance, we appear to have stumbled upon an early eighteenth-century version of a stag party. Gathering around a table “laden with a huge sirloin,” amid the merriment of drinking large quantities of wine, the “brothers” considered whether to expel one of their members for an infraction against “our most gallant and joyous constitutions . . . the statutes and regulations of our order.” Apparently Brother Jean, instead of following the rules “to be always merry, high-spirited and happy,” had fallen in love, “the complete opposite of all joy,” and was planning to get married, even though marriage was “the grave of all laughter and fun.” The Grand Master asked the assembled brothers to decide if they should condemn the young man. His brother by birth rose to his defense, reminding those assembled that no woman could resist such a handsome face. Jean got off with a small fine.1

The knights, however jubilant, would have disappeared from history if the record of this meeting had not been preserved in the papers of the notorious English freethinker John Toland. In 1710 he had been living in The Hague for two years. He may have been present at the meeting, raising his glass and chatting in French, which he knew quite well. The Toland connection and the early trappings of freemasonry—a movement only just emerging in Scotland and England and not yet implanted on the Continent—suggest that this was no ordinary gathering. Who were these “brothers” so enamored of their “constitutions”? The account in Toland’s papers came from the pen of the knights’ secretary, Prosper Marchand, Picart’s close friend and fellow Protestant exile who had within the year come with him from France to start a new life. In the nascent Republic of Letters Marchand acted as a jack-of-all-trades: he edited, published, and wrote books, including the first history of printing; he worked as a journalist; he bought and sold books; and he acted as a literary agent, matching writers and their projects to publishers and sorting out their contractual disputes. Marchand loved to be involved in slightly risky, even risqué, publishing ventures but usually without putting his name to the project. He circulated forbidden books and manuscripts but somehow managed to avoid legal trouble.2

A closer look at those present at the meeting reveals an international network of publishers who had gathered in the relative freedom of Dutch cities. The Grand Master was Gaspar Fritsch, who together with fellow German and “cupbearer of the order” Michael Böhm, owned a publishing company in Rotterdam. Back in Germany the Fritsch family, in conjunction with the Gleditsch clan, had developed one of the most important publishing houses in the book capital of Leipzig. Gottlieb Gleditsch was treasurer of the knights that evening in The Hague, and it was he who defended his older brother Jean Frederic (or Johann Friedrich) when it became known that he planned to marry. Picart served as graffiti master and “illuminator” of the order; by July 1710 his engravings were already listed for sale by Fritsch and Böhm in Rotterdam, Marchand in The Hague, and J. L. de Lorme in Amsterdam, the last being one of the Dutch Republic’s biggest publishers. Less known as a publisher at the time was Charles Levier, the anointed buffoon of the knights, who was without question the most daring of the bunch. Yet another French Protestant refugee, Levier would publish in 1719 what must count as the single most infamous book of the eighteenth century, a work he called La Vie et l’esprit de Spinosa [The life and spirit of Spinoza]. Two years later Michael Böhm republished the same text under the title for which it would evermore be known, Le Traité des trois imposteurs [The treatise of the three impostors].3

Are we hearing echoes here of an ordinary stag party or of a subversive conventicle of freemasons and atheists? There were no doubt elements of both but also of something else. The chilly November evening brought together men in the book trade who would thrive in a new marketplace of religious ideas. They were not just in it for the money that could be made, though that was hardly irrelevant. They met to celebrate and encourage one another in their common quest for knowledge, especially knowledge about religion. Their ways of socializing were resolutely secular, and in the end their books often had a subversive impact, not because they were explicitly atheistic, but because they encouraged readers to distance themselves from religious orthodoxy of all kinds. Religious belief and practice became an object of study for these men rather than an unquestioned way of life. They wanted to put on the table all the possible opinions about religion. They published to foster an open and critical discussion about religion. But they did not necessarily reject it. The Treatise of the Three Impostors would not appear for another nine years (although Levier had it in hand as early as 1711), and it is not at all evident that it represents the common thinking of these men in the book business. What they surely believed was that even the most notoriously atheistic ideas should be available to the reader, who should be free to form his own opinion of them. Bernard and Picart’s Religious Ceremonies of the World explicitly put forward these same premises, which would prove so crucial to the Enlightenment in the decades that followed. Immanuel Kant provided the enduring motto for the Enlightenment in his 1784 essay “What Is Enlightenment?”: sapere aude! [Dare to know!]. By 1784 this ideal was widely shared among the educated classes; sixty or sixty-five years earlier, when Bernard and Picart prepared their great work, it had a much sharper cutting edge.

Jean Frederic Bernard may or may not have been present among the Knights of Jubilation, but his path had certainly begun to cross with those of Picart and the other knights. In 1709 he corresponded with Marchand, still in Paris, concerning his book brokerage. The exact circumstances of Picart’s first meeting and decision to collaborate with Bernard are unknown, but by 1712 Picart had moved to Amsterdam, where Bernard also lived. In that same year Picart married Anne Vincent, the daughter of a paper merchant. His first wife had died in France in 1708. Picart and his new wife set up shop on the busy Kalverstraat, known as the center of the book trade as well as of money transactions and prostitution. Bernard lived and worked there from 1707. Born in southern France, he had fled with his family to Amsterdam as a child. In 1704 he had gone to Geneva, another Protestant stronghold, to set himself up as a broker between the Genevan guild of booksellers and their counterparts in Amsterdam. In 1711 Bernard anonymously published under a false imprint his Reflexions morales satiriques & comiques, sur les Moeurs de nôtre siécle [Moral satirical and comic reflections on the mores of our century; hereafter Moral Reflections], which used a Persian philosopher to criticize religious fanaticism in Europe and provided a prototype for Montesquieu’s Persian Letters a decade later. Did Picart already know Moral Reflections or its author? We cannot be certain, but Jean Frederic was mentioned by name in a letter written by Picart’s father-in-law, Ysbrand Vincent, in January 1713. In that year Picart enrolled in the same Amsterdam booksellers guild that Bernard had joined two years earlier. By then, they no doubt knew each other.4

A new literary society set up in The Hague in 1711 was typical of the intellectual aspirations of this circle. Did the group grow out of that evening in The Hague the previous year? The ubiquitous Marchand recorded its minutes from 1711 until 1717, and just like the knights, the society maintained an air of secrecy and its members appear to have called one another “brother.” It included leading Dutch intellectuals alongside the usual cast of French refugees and other foreigners. In 1713 the club began publishing in French a Journal Litéraire [Literary journal] that specialized in discussions of new literature, religious issues, and Newtonian science. In the more anodyne form required by regular periodical publication (as opposed to anonymous publications under false imprints), the new journal capitalized on the public’s growing demand for new approaches, especially in matters religious. Its first pages announced that the journal was the work of “several persons from different countries, who have formed a kind of society, whose unique goal is public utility and instruction.”5

The Hague literary society may also have consciously imitated a circle in Rotterdam centered around the English Quaker merchant Benjamin Furly, who was a friend to many of the men in the new club. Furly’s circle included the famous skeptic Pierre Bayle; the notorious English republican Algernon Sidney; the republican and moralist Anthony Ashley Cooper, the third earl of Shaftesbury; John Locke; William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania; and Charles Levier, among others. Furly had held meetings in his home of this literary and philosophical society known as The Lantern. Its name, possibly indebted to the Quaker notion of “the inner light,” also suggests its role in propagating early Enlightenment ideas. The Furly circle was in many ways the epicenter of the first generation of the European Enlightenment. Before his death in 1714 Furly had established contact with many of the aspiring young intellectuals and bookmen who will become part of our story.6

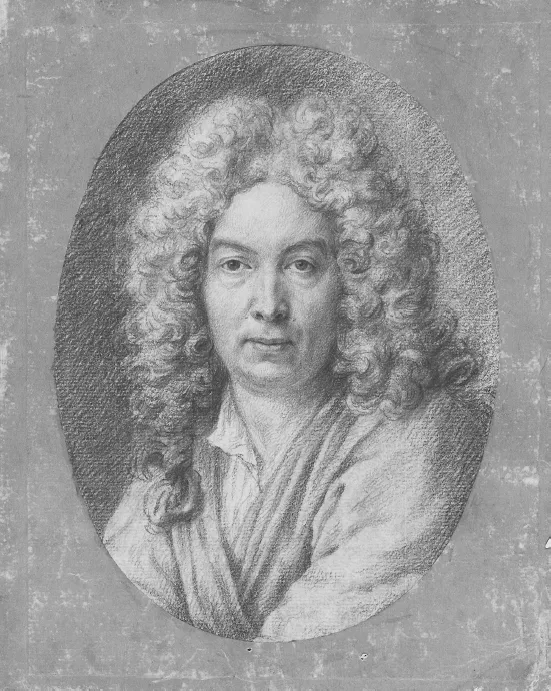

1.1 Bernard Picart as a young man. This self-portrait in red chalk is very similar to the mezzotint portrait of Picart produced by Nicolaas Janz. Verkolje in 1715 after a 1709 painting by Jean Marc Nattier (see Figure 6.2). In 1709 Picart was thirty-six years old. (Rijksmuseum, Prentenkabinet M. RP-T 1965)

Readers of the new Journal Litéraire, the editor recounted, had for some time bemoaned the lack of a publication to explain the intellectual stakes of new books. And what were these books? Many refuted atheism—and thus intentionally or unintentionally gave atheism a kind of audience—and others were among the best-known supporters of greater latitude in questions of religion, works by men like John Tillotson and Samuel Clarke in England. The editors explicitly supported freedom of conscience (“a good granted by God himself “) but carefully insisted that they would offer no public positions on matters of theology or philosophical subjects directly pertaining to religion. Instead they would give faithful extracts of the works under review and would “offer the different opinions to public scrutiny.” A decade later Bernard and Picart would emulate this same strategy in Religious Ceremonies of the World. Picart himself owned the works of Tillotson and Clarke. Bernard went a step further and republished them time and again during his life.7

The rationale the journal editors gave for their position tells much about the tenor of religious debate at the time, even in the relatively tolerant Dutch Republic: “Everyone believes himself orthodox in his sentiments, and everything outside of the sphere of his opinions appears to him far removed from Holy Doctrine. Thus, no matter what position we take, we would never be able to avoid the odious label of heretics, with which one is so prodigal in our century.” They drew the line at atheism, however. Silence could not rule when it came to those who “declare themselves against all religion in general,” and so they persistently returned to this theme, prompting the reader to wonder if they were not protesting just a bit too much. The journal also provided lively commentaries on intellectual life in Paris, focusing in particular on the quarrel between Jesuits and Jansenists that was erupting at just that moment. The editors clearly favored the Jansenists against the “slavish bishops of the Society of Jesus [Jesuits],” but even the Jansenists came under fire for being “opinionated.” Religious Ceremonies of the World would express similar positions: a preference for Jansenism over orthodox Catholicism, an underlying tension about atheism (explicitly rejected but not negatively portrayed), and an insistence on the right of the reader to decide for himself in religious matters. This emphasis on choosing for oneself was inherently heretical for many of the world’s religions.8

As the proliferation of French-language publications like the Journal Litéraire shows, the Dutch Republic had been profoundly affected by the arrival of Protestant refugees from France. Although Huguenots had fled to Switzerland, Prussia, England, and even the American colonies, the greatest number had sought safe haven in the Dutch Republic. Of the estimated 150,000 Protestants who left France, some 50,000–70,000 found new homes among the Dutch. In Amsterdam the influx transformed the character of the city. After 1685 almost one-fifth of its population was of French-language origin. Popping up across the city were French quarters, French shops, schools, watering holes, notaries and lawyers, even French-language churches. The attraction of the Dutch Republic is not difficult to explain. Francophone communities had already taken root during the first half of the seventeenth century, when Protestants fled northward from the southern Netherlands as Catholic armies recaptured territory lost in the uprising against Spanish rule. Once the Spanish had been forced to officially recognize Dutch independence in 1648, the Dutch Republic served as headquarters of the international Protestant resistance against the imperial aspirations of the French king Louis XIV. Dutch city councils eased guild and citizenship regulations and offered subsidies to the newcomers. In addition, no law mandated church membership or the baptism of children, and no tithe favoring a single faith was levied on believers and unbelievers alike. Some French refugees were horrified by such freedom, but others must have found it liberating.9

Publishing offered young Huguenot intellectuals like Bernard and Picart an unusual opportunity. Printing of books and pamphlets had played a crucial role in the development of Protestantism from its beginnings. Without the printing press, Luther’s break from Rome would have remained a tempest in a teapot. Print fed polemics between Protestants and Catholics and among the various Protestant sects as well as different Catholic factions. It could also on occasion threaten the very foundations of Christianity. In 1685 two Dutch presses printed copies of a book in French censored by the French authorities, Richard Simon’s Critical History of the Old Testament. A Catholic priest, Simon brought together the best available biblical criticism to show that the text of the Old Testament had been repeatedly altered over time by Jewish authorities. If the Bible was a historical document, could it still be considered a sacred instrument of revelation? Controversy raged all over Europe, even among Protestants who saw Simon as carrying forward the efforts of Hobbes and Spinoza to question Moses’s authorship of the Pentateuch. The intellectual circle around Furly took a special interest in discussing Simon’s many books that effectively historicized the Bible, even though Simon believed himself to be a devout Catholic.10

Despite or even because of these controversies, the book trade had its allure, especially for Huguenot intellectuals with nonconformist religious ideas who enjoyed few other career options. Positions in the Dutch church and universities were strictly limited to those subscribing to orthodox Reformed theology. Skeptics and seekers need not apply. Even Protestant clergy who held liberal theological positions faced harassment from the consisto...