- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

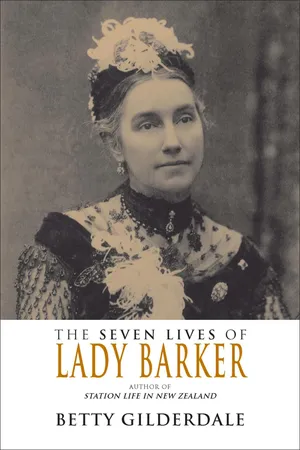

Providing a personal perspective of domestic life in the 19th century, this fascinating biography of Lady Barker sheds light on a Victorian author, Anne Stewart, who lived in England, India, New Zealand, South Africa, Mauritius, Australia, and Trinidad through the course of her life. Illustrating the trials and tribulations of being a female author during that period of time, this volume also demonstrates how Anne's life was impacted by momentous historical events, such as the Indian Mutiny and the Zulu Wars. The only biography on Anne Stewart, it reveals the female perspective of what it meant to be a wife and mother during the greatest expansion of the British Empire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Seven Lives of Lady Barker by Betty Gilderdale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Colonial Daughter

Chapter One

Almost the first thing Lady Barker (later Lady Broome) could remember of her childhood was having her fortune told by a Staffordshire gipsy one summer afternoon in the 1830s. The old woman took her hand and predicted: ‘This hand cannot close on money – you will never be rich. Sometimes the stream of gold will be full and free, sometimes scant and slow but it is never quite dry.’ Seventy years later the owner of the hand was to comment ruefully: ‘This utterance has come exactly and literally true and the remembrance of it has often been a comfort in hard times.’

The gipsy then turned her attention to her subject’s small feet and pronounced that they would ‘Wander up and down the earth, north and south, east and west to countries not yet discovered,’ dramatically concluding, ‘Earth holds no home for you, earth holds no grave, you’ll be drowned!’ She was not drowned but the rest of the prophetic utterances were uncannily accurate. Mary Anne Stewart, as she then was, went on to lead an adventurous life at a time when most crinolined Victorian women were restricted to a life of protected domesticity.

The old gipsy’s prophetic powers were probably reinforced by knowledge of the family staying at Tixall Lodge on Cannock Chase. In all likelihood the nursemaid had already unburdened herself on the subject of ‘Miss Annie’ – that this vivacious, lanky child was a handful, always needing to be occupied or she would be into mischief. That she had cut open a toy cow to examine its insides, then discarded it in disgust when it was found to be empty. That she had actually pulled her doll’s teeth out and refused to play with it when she found no brains in the head and the body stuffed with straw. The nurse would almost certainly have enlarged upon the fact that on one occasion Annie had covered her little sister Dora with hair pomade to make her grow more quickly, and on another, in pursuit of the same aim, had ‘planted’ her sister in a hole in the garden, then watered her to assist germination.

What adults considered to be unacceptable behaviour almost certainly indicated a scientific mind that needed to experiment, observe and record: abilities that later stood her in good stead as she chronicled her journeys all over the world. These attributes may have been inherited from a distinguished pedigree that included three army surgeons as well as Alexander Mackenzie of the ill-fated Darien venture. This was a scheme originated by William Paterson, founder of the Bank of England, to form a settlement on Darien (Panama), which would become a centre of free trade. An expedition to set up the enterprise left Scotland in 1698 but collapsed in disease and anarchy, although Mackenzie’s appetite for the Caribbean had been whetted. He settled in Jamaica and it was there that his young descendant, Mary Anne, was born on 29 May 1831, in Spanish Town, where her father, the Hon. Walter Stewart, was Acting Colonial Secretary.

Annie’s travels began at a very early age. By the time she was four she and her younger sister Dora (Maria Theodora Margaret) had already crossed the Atlantic to stay at Woodville, Lucan, near Dublin, home of their paternal grandfather, the distinguished Indian Army General Sir Hopton Stratford Scott. It was the first of the seemingly endless peregrinations of colonial children sent back to Britain to escape the exigencies of tropical climates and to be educated.

That education, however, was to become the butt of trenchant criticism from its recipient. Modern educators would quickly recognise that Mary Anne Stewart exhibited all the signs of a highly intelligent child who needed constant extension and occupation. Unfortunately, in the over-protected nurseries of the upper classes there were few opportunities to develop an enquiring mind and Annie later wrote of her childhood:

I was a regular tomboy, besides being the most mischievous child in the world. I did not mean to be naughty, but it seemed so dreadful to be always told to be quiet. No one ever thought of finding me any occupation and as I was forced to seek it for myself I spent my time in a series of scrapes … Lesson hour was the happiest part of the day but unfortunately it lasted only a short while. I used to envy the servants their regular duties and whenever I read in little books of children being obliged to work hard for their parents I thought it must be much happier than having nothing to do, which was my constant complaint.

At least when she was old enough to read she could experience vicarious adventure, although in the 1830s there were very few suitable children’s books available apart from ‘chap books’, fables and traditional tales. Her greatest treasure, read and re-read, was Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, which inspired her with a longing for independence and self-sufficiency that never really left her.

In Holiday Stories for Boys and Girls (1873) she wrote of a time when her parents were on leave and they were all living in a large country house in Kent. Fired by Robinson Crusoe’s example, she persuaded her mother to allow her to build a ‘cabin’ in the grounds. This was to be located beyond a stream, and she dragooned various cousins to help her carry building materials and provisions over to it. She clearly identified herself with the boys when she suggested that ‘women and children’ (i.e. girls and dolls) should be left behind because the terrain was too rough, but after a while even the boys became discouraged by the brambles and the midges so she would go alone, accompanied only by the dog. She recorded: ‘I never minded any discomfort. In fact I rather liked it as it was more like my idea of the real thing.’ In the end the expeditions were stopped. She had decided that the best way to clear the brushwood and bramble would be to burn it. This worked very well until her blouse caught fire and she narrowly escaped being badly injured.

Fire always fascinated her. On another occasion she accidentally burnt down a dolls’ house. The gardener had made it out of packing cases, but although it had an upstairs and a downstairs there was no connecting staircase. Annie, with her passion for absolute realism, even in replicas, noted: ‘That was the beginning of my disenchantment.’ Various aunts had made curtains and carpets and bought toy furniture for it but she worried that things were out of proportion, that the clock was too large for the little table, that there was an umbrella stand but no umbrellas. One day, when she and Dora were pretending that a peg-doll baby was teething, Annie suggested lighting a fire in the toy grate to keep it warm. To their consternation the fire spread to the rest of the dolls’ house. The tin furniture melted, the house was reduced to a heap of ashes and she was severely lectured by horrified adults.

One way of keeping Annie out of mischief was to divert her attention to animals. She loved the dogs, horses and cats that were always an integral part of the Stewart ménage, but she was particularly interested in birds. She managed to persuade her parents to let her breed turkeys and went about it quite scientifically. She read numerous books on the subject and followed their instructions faithfully. For a time everything went well. The chicks hatched and flourished, and eventually were allowed out into a paddock to feed. Then, mysteriously, small turkeys would be found lying senseless or dying on the ground. Annie was so upset that her parents and the outdoor staff agreed to keep a watch on the paddock. Before long the mystery was solved. The children’s quiet, well-mannered bay pony, Alarm, for all his good nature with people, apparently had an aversion to turkeys. He would quietly go up to each chick in turn and kick it, so that in the end, out of the 100 turkeys that had hatched, only two were left. It was an inauspicious beginning to a farming career, but Annie was not to be beaten, and throughout her life, whenever circumstances allowed, she established a poultry yard.

By now the girls had two younger brothers, Hopton Scott and Walter Langford. When their parents returned to Jamaica after leave, little Walter and Hopton went with them but the two girls remained behind to be cared for by their Shropshire and Staffordshire cousins, the Hills, Maynes and Corbets. It would seem that the Maynes took the lion’s share of the burden because in most of Annie’s descriptions of her childhood it is Tixall Lodge, Cannock Chase, in Staffordshire, that features most evocatively. The Maynes were her mother’s cousins, and although Victorians tended either to rent their homes or buy them on short leases, Tixall Lodge seems to have been occupied by the Mayne family over a long period. The term ‘Lodge’ is misleading. It was an imposing early Victorian house whose large stone mullioned windows looked down through park-like grounds to a lake, which obligingly froze every hard Staffordshire winter and was ideal for skating. In bad weather the outbuildings were exciting places for hide-and-seek and imaginative play; in summer the extensive fields and gardens enabled the children to explore and to observe plant and animal life.

The grounds of the Lodge adjoined those of an older house, Tixall Hall, whose fine Elizabethan gatehouse is still standing and was briefly a prison to Mary Queen of Scots in 1586. During much of Annie’s early life it was occupied by James Tyrer, a rich Liverpool merchant, guardian to his great-niece and -nephew, Annie and William (Trappie) Woodward. They became frequent companions of the Stewart children, and although all of them lacked parents they seem to have been happy enough in benign surroundings under the consistent care of carefully appointed nannies and governesses.

Holidays were often spent with the extended Scott family in Lucan, where Annie’s inventiveness was not always appreciated by one of her aunts. She was by now nine years old and her enquiring mind led to an interest in aerodynamics. She made wings from newspaper that she stitched on to whalebone supports, and managed to convince her cousins that she could fly. She herself had serious misgivings as to the truth of this claim but when challenged by her cousin Hopton she felt duty bound to convince him. He made her climb onto a wall of boxes three metres high that he had built and, when she stood hesitating at the top, he pushed her. The wings, of course, were worse than useless and she landed unconscious on the floor. Needless to say, her aunt confiscated the wings, but Annie felt vindicated because her younger cousins all believed she could have flown had she not been pushed. The same cousin Hopton, destined for a military career, always teased her mercilessly, and certainly never offered any concessions to her because she was a girl. If they played at ‘battles’ Annie was usually made general of the opposing army and suffered numerous blows from his rolled-up paper truncheons.

In stories that offer a vivid picture of childhood in the early 1840s, she details expeditions with her boy cousins to collect birds’ eggs and butterflies, and how together they set up a fresh-water aquarium. Her skirts hampered her from joining in cricket and football, she was not overly enthusiastic about their ferrets or about their ‘persistent drumming on banjos’, but she could, and did, enjoy experimenting with the boys’ chemistry set, and was instrumental in helping them to plant a ‘stink bomb’ in the library. Wisely, they then took themselves off on a strategically long walk, only to find on their return that every window of the house was open and the whole establishment smelt of a mixture of gas and addled eggs.

As a result of their escapade the boys had various physical penalties inflicted upon them. Annie escaped a beating but was sent to bed at 5pm with no supper, and was forced to wear an instrument of punishment named ‘the nightcap of disgrace’. This garment was made of thick white muslin with 10-centimetre-wide frills and with ribbons so cruelly starched that they nearly guillotined her when they were tied vindictively with a jerk beneath the chin. She confessed that it was an effective deterrent, so that: ‘Whenever I contemplated wickedness the thought of this thing changed me into a good little girl – for the time being.’

Love of the countryside generated in her childhood never really left her, and she was always more at home with outdoor pursuits than with formal occasions. From an early age ‘parties’ were a source of dread. Deeply conscious that she lacked Dora’s pretty femininity, that she was unusually tall and thin and that her complexion was sallow, Annie recalled with horror being made to wear a pea-green party dress that seemed designed to reveal her worst features. In any case, children’s parties in those days were rather dull affairs. The Prince Consort had not yet introduced the idea of gifts around the Christmas tree, and conjurors were not as fashionable as they subsequently became. The only activities offered the children were formal dances such as the quadrille and later the polka, and Annie was often embarrassed because she was taller than her young male partners. She did record more informal and spontaneous amusements, however, such as when another of her cousins, Henry Byng, later Earl of Strafford, was found ‘sliding rapidly down the balustrade to the serious detriment of his new kerseymere suit’.

In June 1843 the girls were joined by their mother, Hopton and Walter at Lady Scott’s home in Lucan, where another sister, Susan Louisa, was born. After the christening, Mrs Stewart left with the three youngest children, and once again Annie and Dora were left in the care of relatives. Although they grew accustomed to these periodic partings from their parents, waves of homesickness would still sometimes overtake them. Years later, writing in Boys (1874), Annie recalled waiting on the steps of Woodville for one of her cousins to arrive back from his English public school for the summer holidays. She vividly described:

the gravel sweep of the drive, the large clumps of evergreens and flowerbeds blooming in front of the house as his parents went to greet him … Child as I was, I remember quite distinctly how this part of the ceremony used always to make me feel inclined to cry, partly, I suppose, because in all my ‘Welcome Homes’ there must of necessity be no parents’ kiss to greet me, and no affection or kindness in the world from other people can quite make up for that loving embrace.

She insisted, nevertheless, that overall her childhood was a happy one. She accepted that separation from parents was an inevitable part of life for children of colonial administrators, but she never ceased to be aware that they were guests in someone else’s home. Writing many years later in Houses and Housekeeping (1876), she recalled the pangs of hunger felt by a fast-growing teenage girl:

I never can forget what I suffered from hunger myself as a growing girl. I used to eat as much as I dared, at the risk of being thought unladylike, at every meal, but oh, what a chronic state of wolfish hunger I lived in between times! In those days girls were fabulously supposed to be ethereal creatures who fed on rose-leaves and dew, but I can safely affirm that from twelve to sixteen years of age I should greatly have preferred the thickest possible bread-and-butter and quarts of new milk. No one grudged me my food, it was simply forgotten that a great growing girl needed a more nourishing and plentiful diet than her elders and betters, and so I used to be offered dainty ‘tartines’ in place of the solid wedges of even dry bread for which my famishing soul craved.

At least during those teenage years her mind was less famished than it had been in earlier childhood. A good governess ensured that she and Dora acquired perfect French, and they spent some time in Paris studying both the language and art. Their lessons in drawing continued in England, and Annie was to prove very talented. A shrewd observer, she was particularly clever at catching likenesses, but she was very critical of the so-called ‘teaching’ that she received. In Colonial Memories (1904) she lamented:

A girl with any musical talent could, of course, go on practising and had a chance of achieving something, but art education must have been at its lowest ebb. It is difficult to believe that a ‘drawing class’ of that day generally consisted of a dozen girls or so meeting at the house of some rising, or even well known artist. The great point seemed to be his name.

She continued:

Drawing materials and every other facility, except instruction, used to be provided by our ‘master’. Perhaps the poor man recognized the hopelessness of his task, but he certainly let us severely alone even in our choice of subjects. We were only asked to copy other drawings and I well remember selecting, as my first attempt at painting, a most ambitious sketch of a pretty Irish colleen with a pitcher on her head, emerging from a ruined archway. I dashed in her red petticoat and blue cloak with great vigour and took little pains with her uplifted arm or bare legs. They must indeed have been curious anatomical studies, for I recollect the master heaving a deep sigh, if not a groan, as I presented my drawing for his criticism. But he made no attempt whatever to teach me how to do better, only took possession of my picture, kept it a few days and return...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Stewart and Mackenzie Family Trees

- Maps

- Introduction

- Part I : The Colonial Daughter

- Part II : The Soldier’s Wife

- Part III : The Farmer’s Wife

- Part IV : The Author

- Part V : The Colonial Wife

- Part VI : The Governor’s Wife

- Part VII : The Colonial Widow

- Sources

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright