![]()

1

A Blank Canvas

The world as it was in the mid- century

Extinct and Endangered

Fascination with the Dodo is engendered almost entirely by its extinction. The phrase ‘As dead as a Dodo’ has become a well-used expression of absolute finality. There is no chance to see it, touch it or rescue it, only a feeling of vexatious regret and a few haunting images and decaying remains. It incites related sentiments that drive the desire to prevent the extinction of animals we know and love. I retain a deep affection for all the breeds that surrounded me as a young boy on our hill farm in the Yorkshire Dales and I am prepared to exert rigorous effort to prevent the extinction of sturdy Dales ponies that provided all the draught power, thrifty Northern Dairy Shorthorn cattle whose Cotherstone cheese filled the stone-shelved pantry with herb-rich meadow redolence, and massive Teeswater sheep with fleeces falling in long pirled ringlets. Now they are endangered breeds and I have learnt it needs more than sentiment to save them. There must be a stronger raison d’être. At the end of the 20th century in the 3rd edition of World Watch List (Scherf, 2000), which listed 6379 breeds, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations calculated that 12% of domestic breeds (mammalian and avian) had become extinct, 26% were endangered and the status of 21% was unknown, leaving only 39% not at risk. Comparison with a later analysis (Bélanger and Pilling, 2019) could indicate that the first two decades of the new millennium had seen a significant decline in the status of breeds. It applied a different classification which suggested a much higher proportion of breeds were at risk, although it appeared to confirm the earlier extinction data.

The information in the World Watch List for Domestic Animal Diversity (or WWL-DAD) on extinct breeds was gleaned from A World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds, Types and Varieties (Mason, 1996) and more than 70% of listed extinct breeds were native to Europe, where more rigorous recording was undertaken. Therefore, the global figure is likely to be understated until further information is obtained from other continents. On the other hand, although we can accept the claim that no British breed has become extinct since 1972, European extinctions may have been overstated if the 72 British breeds listed in WWL-DAD as extinct reflect the application of a similar methodology in other countries. Several very similar local varieties, listed as separate breeds, often were amalgamated into a new breed such as Aberdeen Angus cattle or Shropshire sheep. South Devon and Devon Longwoolled sheep were indistinguishable to the untrained eye and came together as the Devon and Cornwall Longwool in 1977. The British Saddleback pig had been created 10 years previously by amalgamation of Essex and Wessex pigs although they shared only a common colour pattern. Some entries on the WWL-DAD extinct sheep list (Kent Halfbreed and Yorkshire Halfbred) were not genuine breeds; the entry for ‘Five-horned cattle’ beggars belief (Mason, 1996, had referred to Fife Horned); and Chester White pigs were a foreign breed imported from USA in 1978. Probably only 85% of British breeds listed as extinct were genuine cases of extinction. It should be noted that a figure of only 26 breeds of large livestock in Britain is commonly quoted as becoming extinct in the 20th century before 1973. If those figures are accepted it would indicate that about 35 recognized breeds or types became extinct in Britain before 1900, with the qualification that conflicting reports from commentators in the 19th and 18th centuries make conclusions less reliable.

Creation and Re-creation

Creative instincts of livestock breeders are evident from the earliest reports of commentators on agriculture and livestock. Even without the benefit of the work of Gregor Mendel, ‘the father of modern genetics’, they were seeking to improve their livestock and the search often extended into procurement of new genetics to achieve their objectives. The Colling brothers, who farmed near the River Tees, were famed for using proven animals, notably Hubback and Duchess in the 1780s, in a policy of linebreeding to superior ancestors such as the Studley bull (born in 1737), and Robert Bakewell is remembered best for breeding ‘like to like’ to improve his Longhorn cattle, but his success also was based on crossbreeding. The foundation for his sheep-breeding project was the existing slow-maturing, long-legged, coarse Leicester used solely for wool production. He created the New Leicester breed in the late 18th century by infusing genetics from faster-maturing, fatter Ryeland sheep and from the old longwoolled Lincoln sheep. It was a style of breeding adopted by many others who created new breeds such as Bonsmara cattle (Afrikaner × Hereford × Shorthorn) and Beefmaster cattle (Brahman × Hereford × Shorthorn) in the 1930s, Santa Gertrudis cattle (Brahman × Shorthorn) and Columbia sheep (Lincoln Longwool × Rambouillet) in the 1940s. They mated breeds with contrasting traits in order to find new and desirable combinations of genes.

Although it was a continual process, the two decades after 1950 witnessed an outburst of ingenuity and innovation. The discovery at Cambridge University of the ‘double helix’ structure of DNA in the early 1950s (Watson and Crick, 1953) was an inspirational event that launched a new surge of biological research. It was also a critical time for both the creation and extinction of breeds. Beevebilde cattle and several breeds of sheep, including Cadzow Improver, Eastrip Prolific and Cobb 101, were created in the 1960s before becoming extinct after a relatively brief presence as peripheral members of the livestock industry. At the same time established British breeds became extinct. Cumberland, Ulster White, Bilsdale Blue, Oxford Sandy-and-Black and Dorset Gold Tip pigs and Blue Albion cattle were among their number, and the last British extinction was the Lincolnshire Curly-Coated pig in 1972. Two of those breeds (Oxford Sandy-and-Black pigs and Blue Albion cattle) are not listed as extinct by FAO because re-created populations adopted the name of an earlier genuine breed. The fifth edition of Mason’s World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds, Types and Varieties (Porter, 2002) describes current Blue Albion cattle more accurately as ‘crosses’ and re-created Oxford Sandy-and-Black pigs as ‘reconstructed’. The Blue Albion became extinct as a result of the foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak in England in the 1960s: the new population is derived from blue cattle of unknown breeding purchased in auction marts and elsewhere. The Oxford Sandy-and-Black also became extinct in the 1960s and the new population has developed from a welter of crossbreeding between a medley of breeds.

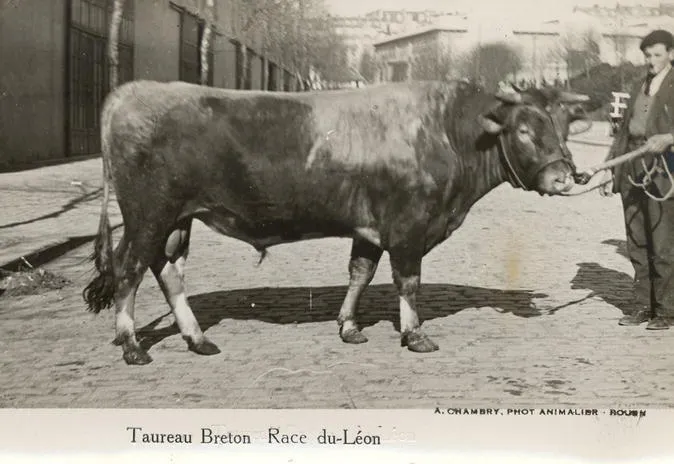

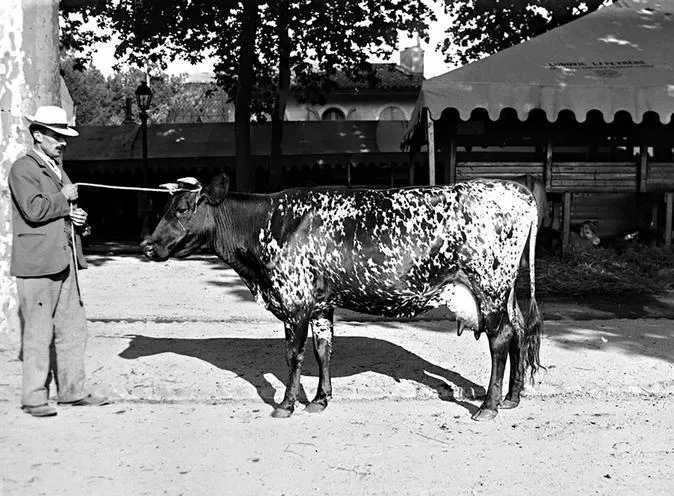

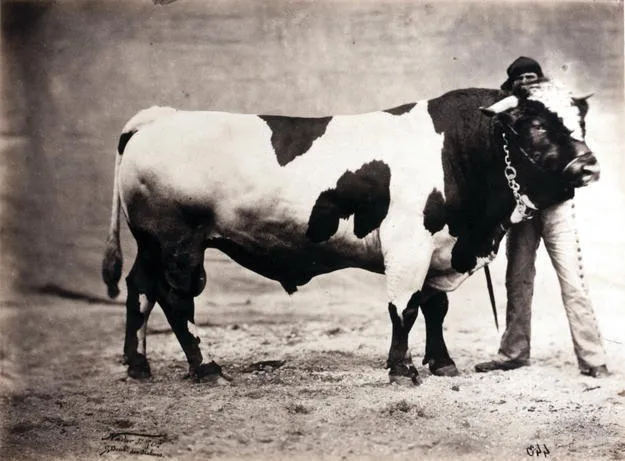

Re-created types are also found elsewhere in Europe. In Italy remnants of the Mucca Pisana were crossed with Chianina in 1980s (Fig. 1.1); and the lyre-horned Garfagnina was crossed with Brown Swiss soon after I saw the last 24-year-old purebred cow in 1980 (Fig. 1.2). In France the ancient lyre-horned Froment du Léon (Fig. 1.3) was very localized and in 1983 was crossed with Guernsey bulls; and the traditional Bordelaise in Aquitaine (Fig. 1.4), with its distinctive pigaillé (speckled) colour, having originated from crossing local animals with Bretonne Pie Noire and Durham cattle, was declared extinct in 1960 before a new population was built in the 1980s on Friesian and Limousin crosses. Switzerland claims the Fribourg (Fig. 1.5), black-and-white sister breed of the popular Simmental, but it became very inbred and was crossed with German Friesian so that it is now a new breed listed as ‘Swiss Holstein’.

There can be no dispute regarding the principle that re-creations, although they may bear a superficial resemblance, never can be genetically the same as the genuine original breed. If official lists are unable to avoid error or misinterpretation, a tipping point may be reached when observers are unable to distinguish fact from falsification, and the latter may be held to be true even then because it is expedient to do so. In some cases, it may be difficult for FAO, as a relatively remote body in Rome, to reach a decision on a local question. Irish Moiled cattle are found throughout Northern Ireland, Wales and England and are classified as a native breed of the UK, but the Republic of Ireland also listed Irish Maol as a native breed although its ‘Country Report’ to FAO in 2002 confirmed that there were no cattle of that breed in the Republic in 1987. It is clear that all evidence must be sifted carefully.

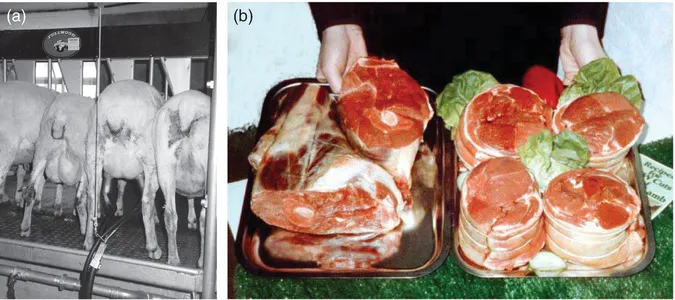

Creation of a new breed is a formidable undertaking. The development and application of a breeding programme requires imagination, expertise and some good fortune, but the major obstacle is breaking into the strongly defended territory of established breeds. Success depends primarily on identification at the beginning of the project of a gap in the market that can be exploited. Some breeds created during the period 1950–1975 merely survived. The Lacombe pig, developed in Canada in the 1950s from Berkshire, Landrace and Chester White foundation stock, enjoyed initial success but is now an endangered breed because existing breeds occupied and defended the targeted market. Other breeds have thrived but success in all cases was hard won. Dorper sheep (South Africa, 1950, Dorset Horn × Blackface Persian) are a hairy meat breed which has been successful. Simbra cattle (USA, 1960s, Simmental × Brahman) are a dual-purpose breed which has spread beyond its country of origin. Polypay sheep (USA, 1960s, Rambouillet, Targhee, Dorset, Finn) are a dual-purpose breed which has expanded its range. British Milksheep (UK, 1970s, Bluefaced Leicester, Dorset Horn, Eastrip Prolific, Lleyn and others) is a highly prolific multi-purpose breed which has developed markets for meat and wool (Fig. 1.6) (Thwaites, 2019). The creation of the last two breeds employed a complex programme, involving more than three breeds, and both have been able to follow a successful path of development.

Philosophy of Livestock Production

Fine-woolled Merino sheep were probably the first breed to establish a precedent for domination of an industry. They burst out of their guarded Spanish stronghold in the mid-17th century, a feat repeated from the early 19th century when they colonized Australia, North America, Russia and eastern Europe (Garron and White, 1985). But a more enduring ...