![]()

1

AGRA

The call of the muezzin to prayer floated over the city of Agra in the dawn, waking up the residents. The summer heat had made even the nights unbearable and Abdul Karim was almost relieved to leave his bed. His young bride was still asleep. It was the few tranquil minutes of the morning that he loved. He walked on the terrace surveying the roof-tops of the neighbouring houses. Not far away he could see the high walls of the Central Jail where he and his father worked. Soon all of Agra would be awake and buzzing, the gullies and bazaars full of traders, artisans, tongah wallahs and people getting about their work. Cows would stand on the crowded streets lazily chewing the vegetables from the vendors’ carts and elephants would sway through the narrow lanes carrying their loads of logs, grain, cotton and carpets to the mandis and factories.

As Karim sat down on a mat to pray, the first rays of the sun fell on the Taj Mahal, bathing it in a warm glow as the gentle waters of the Yamuna flowed behind. Further upstream, strategically positioned at a bend in the river, stood the impressive Agra Fort, a towering piece of architecture built in red sandstone by the Mughal Emperor Akbar in the sixteenth century, when he was at the pinnacle of his glory. Agra was known then as Akbarabad, capital city of the Mughal Empire. Within the walls of the Fort lay the history of four generations of the Mughal Emperors: tales of war, romance, court intrigues and brutality. It was in the splendour of the Diwan I Khas, or the Hall of Private Audience, with its marble columns inlaid with rich gemstones – lapis lazuli, garnet, jade, jasper and carnelian – that Emperor Shah Jehan had received the embassies of William Hawkins and Sir Thomas Roe, who came seeking permission for the East India Company to trade with India. The English and Dutch subsequently established their factories in Agra. It was in the Jasmine Tower of the Fort that the ageing Shah Jehan was imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb, and here that he languished till his dying day gazing through the tiny prison window at his beloved Taj Mahal, the mausoleum he had built for his Queen, Mumtaz Mahal.

Karim’s family had lived in Agra for the last four years, enjoying the city’s rich Mughal heritage, which was now combined with the spit and polish of British administration. The original family home was in nearby Farrukhabad in the United Provinces. Karim’s father, Haji Wuzeeruddin, had been brought up by his stepfather, Maulvi Mohammed Najibuddin, who took care to provide him with a good education. In 1845 Najibuddin was employed as private secretary to an Englishman, William Jay, who was very kind to the family, encouraging young Wuzeeruddin and employing him in his services. From 1856 to 1859, Haji Wuzeeruddin worked in the Vaccine Department of Agra. In 1861 he received his diploma as hospital assistant and served in the 36th Regiment North India from November 1861 to March 1874 working in various cantonment towns in north and central India. It was in Lalatpur cantonment near Jhansi that Abdul Karim was born in 1863.

Karim was to grow up in an India very different from that of his father – one that was governed directly by the British Crown and not the East India Company. Six years earlier, the land of his birth had been the principal theatre-ground of the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Haji Wuzeeruddin had been an eye-witness to the event that would be described later by Indian nationalists as the First War of Indian Independence. Karim’s birthplace, near Jhansi, was synonymous with the fiery Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, who had donned battle armour, mounted her faithful steed and led her troops against the forces of the East India Company during the Mutiny.

Soldiers from the cantonment of Meerut in the United Provinces had taken up arms against their commanders, liberating imprisoned soldiers and killing many English officers. Soon neighbouring towns of Agra, Cawnpore (modernday Kanpur) and Gwalior were captured by the mutineers and the rebels began plotting the downfall of the East India Company. They looked north to Delhi, where the ageing Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, still held Court in the Red Fort and chose him as their symbolic leader. The eighty-two-year-old, famous more for his ghazals and Urdu poetry than for his statesmanship, declared himself Emperor of India, directly challenging British authority. The rulers from various central and northern Indian states rallied under his name. The mutineers met with initial success, British forces not being prepared for the rebellion. The siege of Delhi lasted for nearly four months, but on 21 September, Delhi fell to the Company troops. Bahadur Shah Zafar was given a brief trial and exiled to Rangoon in Burma; the last Mughal Emperor and descendant of Tamerlane, leaving Delhi unceremoniously in an ox-cart, ending an era of Indian history.

The British revenge was extreme. Hundreds were hanged after elementary trials and others were executed by tying them to the mouths of cannons and blowing them up. Delhi was desecrated, many of its historic monuments raided and plundered, artefacts and manuscripts looted and destroyed, and hundreds of ordinary civilians executed. The residents of Agra were fined collectively for helping the rebels. Many Mughal buildings and houses in Agra were demolished. The blood of the mutineers stained the dusty plains of central and northern India as they were hanged from trees and public posts as a warning to anyone who challenged Company rule in the future. Karim was born on the same land six years after the guns of the mutineers were silenced.

He was only thirteen when Queen Victoria was given the title of Empress of India in 1876 by Benjamin Disraeli. The East India Company had been dissolved in 1858 and ruling power transferred directly to the British Crown. The Secretary of State for India now dealt with Indian affairs in Westminster and the Viceroy represented the Crown in India.

The Queen was delighted with her new title and sent a message to the Delhi Durbar held on 1 January 1877: ‘We must trust that the present occasion may tend to unite in bonds of yet closer affection ourselves and our subjects, that from the highest to the humblest all may feel that under our rule the great principles of liberty, equity and justice are secured to them.’ Karim would have heard this message as a teenager living in Meerut City.

With the British Crown now directly in charge of the administration of the provinces, radical changes were made. The railways were constructed with frenetic zeal to provide direct and quick access to the interior of the country, linking Cawnpore, Lucknow, Meerut and Agra, the major northern Indian cities that had been touched by the Mutiny. The East India Railway connected Calcutta directly to Delhi, and the Central India Railway connected cities like Bombay and Baroda to the north.

After the Mutiny, the British had regulated the running of the Indian army and Karim lived his early life in the cantonment of Lalatpur and Meerut City, watching the parading soldiers and dreaming of one day being in uniform. He was the second of six children, with an elder brother, Abdul Azeez, and four younger sisters.

The 36th Regiment then moved to Agra and Karim was placed under a regular tutor, though he spent most of his time with the other boys playing in the fields. ‘In my elementary education I regret I spent more time in play than in work,’ he wrote later in his memoirs. ‘Being my mother’s favorite, I was rather over-indulged and my studies were very irregular.’1 In 1874 Haji Wuzeeruddin was transferred to the Second Regiment of the Central India Horse which was stationed in Agar, an area on the border of Rajputana and the Central Provinces (present-day Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh). After a year’s stay in Agar, Wuzeeruddin sent for his family who travelled there by bullock carts covering twenty-two miles a day. It took them one month to reach Agar.

In Agar, Karim’s parents paid more attention to his education and he was handed over to a private tutor, a Maulvi (Muslim scholar), with whom he studied till the age of eighteen. He was taught Persian and Urdu, the Court language of the Mughals, and read books on Islam and the Prophet.

In 1878 Britain was entangled in the Anglo-Afghan war and the following year, Haji Wuzeeruddin received orders to go to Afghanistan with the First and Second Regiments of the Central India Horse under the command of Col Martin. Karim, who was seventeen at the time, was overcome with grief at this news as he felt he would never see his father again.‘I at once made up my mind not to remain behind in ease and comfort and let my father go unattended to encounter the hardships of the campaign, especially when I felt confident I could be of assistance to him,’ he wrote. Despite the objection of his parents, Karim accompanied his father on the journey.

They passed through Lahore, ‘a splendid city’, where the mausoleums and shrines were ‘magnificent and numberless’, to Jhelum, Rawalpindi and Peshawar, stopping at the forts of Basawal, Sandamuck and Jellalabad. Karim was eager to explore, taking in the rugged countryside and the tribal terrain. It was famously to the fort of Jellalabad that the exhausted British soldier, Dr William Bryden, had come on 13 January 1842; the lone survivor of 16,000 troops who perished on the road from Kabul during the First Afghan War of 1837–42, a picture etched forever in the minds of the British administration and captured dramatically on canvas by artists to remember the war’s high casualties. Nearly forty years later, Afghanistan remained on the boil and the British constantly feared that the Russians would attempt to enter India through Afghanistan. The Second Afghan War broke out in 1878, after the British and the Russians clashed over setting up a mission in Afghanistan.

No sooner had Wuzeeruddin’s regiment reached Jellalabad, when they were ordered to start at once on the famous march to Kandahar under General Roberts in August 1880. Roberts had been a junior officer during the siege of Delhi in the Mutiny. Within three hours the soldiers were on the road. Wuzeeruddin accompanied them as a medical assistant, but despite Karim’s pleas to remain, he had to turn back as he had no formal position in the army. Karim covered the 500 miles back from Jhelum to Agra alone, returning to find his mother sick with worry.

The historic march from Kabul to Kandahar with 10,000 men ended in a resounding British victory and the defeat of the Afghan lord, Sardar Mohammed Ayub Khan. A few months later the Second Afghan War was over and General Roberts returned triumphantly to England where he was knighted.

When Wuzeeruddin returned after the war, he was given four months’ leave. ‘All our family were so pleased and happy to see his face once more,’ wrote Karim.‘We were all thankful to Providence for having brought us all together again.’

Karim travelled with him again to Kabul, where he marvelled at the sight of the Khyber Pass, the fifty-three-kilometre narrow road that cuts through the Hindu Kush mountains, used by invaders for centuries since the time of Alexander the Great. The precipitous cliffs guarded by the fierce Pashtun tribes, the austere forts standing in bleak mountain deserts and the famous bazaars of Kabul overflowing with watermelon and dry fruits, were a far cry from the gentle plains of the Yamuna that Karim had grown up in.

When they returned, Karim took up employment with the Nawab of Jawara, who appointed him as the Naib Wakil (assistant representative) to the Agency of Agar. Meanwhile, the British government issued an order permitting the exchange of military for civil appointments and Wuzeeruddin transferred to the Central Jail at Agra. It was while Karim was working for the nawab that his family arranged his marriage in Agra and Karim took two months’ leave to travel for his wedding. He returned to Agar feeling lonesome and homesick. ‘There was however no help for it as duty must conquer sentiment so I remained,’ he wrote, working steadily for another twelve months before he took a month’s leave to return to his family.

After three years’ service with the Nawab of Jawara, Karim resigned and joined his father at Agra, taking up a position as a vernacular clerk to the superintendent of the Central Jail. His salary was fixed at Rs 10 a month. Both father and son were now employed at the same place. Wuzeeruddin moved with his family to the Hariparbat area near the jail. The family owned about five acres of land in the surrounding area. Karim enjoyed hunting with his brother in the forests around Agra, which were full of deer, black buck and tigers. The surrounding lakes of Rajasthan were the nesting grounds of a variety of wild fowl, particularly the migrating cranes who came every winter from Siberia and stayed till spring. Agra, the city of the Taj, was now the stable family home. It was here that Karim settled down with his young bride. His wife’s brothers also worked at the jail and the closely-knit family soon became well known in the area.

On that summer morning in Agra, when Karim looked out over the city, he did not know that his life was about to change.

The first stirrings of human life had begun and the banks of the Yamuna were already crowded with camels and elephants, led by their owners to drink and carry back the day’s water supply. In the markets of Loha Mandi and Sadar Bazar the traders were opening their red cloth-bound ledgers and fixing the commodity prices for the day. Spices, cotton, wheat, gram, oil, sugarcane – all the produce of the fertile region – would pass through their keen fingers as they struck their deals. Agra had been the hub of trade activity since Mughal times and so it continued under the British as the trade corridor that connected Central and West India on one side and the rugged North-West on the other.

Artisans were also at work. Carpet weavers were streaming into the looms of Otto Weyladt and Co., the largest carpet manufacturers in Agra, to weave the finest carpets for the export market. In the narrow streets and shops around the jail, the craftsmen were beginning their delicate job of stone inlay work, practised for centuries since the time of Emperor Akbar, cutting the huge slabs of marble and fashioning them into exquisite handicrafts set with precious gems.

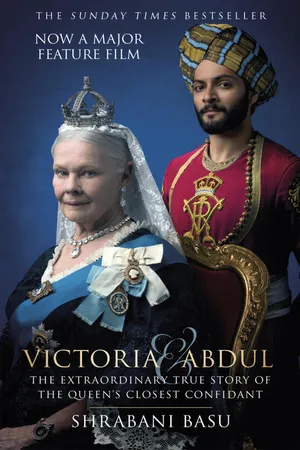

As the clinking sound of their hammer and chisel striking the stone began to fill the air, Karim said goodbye to his father, adjusted his pugree and strode out of the house towards the Central Jail. A tall man, nearly six feet in height, with dark intense eyes and a neatly clipped black beard, he looked impressive. Today was an important day. He had been summoned to meet with John Tyler, the jail’s superintendent.

Tyler was a busy man. A doctor by profession, he was well loved for his warmth and geniality but known for a lack of tact and a hot temper.2 As an Anglo-Indian he was fluent in Hindustani and at ease with the natives. Tyler had just returned to Agra from London from the successful Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, at the inauguration of which the second verse of the English national anthem had been uniquely sung in Sanskrit. He had been in charge of thirty-four inmates from Agra Jail who had attended the exhibition. The inmates had been schooled in carpet weaving as part of the jail rehabilitation programme, a tradition started by Emperor Akbar who brought the finest carpet weavers from Persia to India as teachers. Since the prisoners had all the time in the world, they could work at leisure to produce the exquisite Mughal carpets in silk, cotton and wool. The jail carpets were internationally famous and the tradition of training the inmates was carried on by the British administration.

The carpet weavers from Agra Jail had impressed Queen Victoria with their skills. It was Karim, Tyler’s assistant clerk, who had helped him select the carpets to send to England for the exhibition and had chosen the artisans, who he had supervised before they left for England. The superintendent of the jail had also wanted to send a pair of traditional gold kadas or bracelets for the Queen and Karim had proven useful again. Tyler found the young man efficient and trusted his fine aesthetic sense. Karim had chosen a pair of kadas set in solid gold, embossed with traditional meenakari, or painted enamel work, with two dragon heads at the terminals. The kadas were wrapped in Indian silk and velvet and packed for the Queen. Tyler’s gift was much appreciated. On 20 September 1886, the Queen wrote to Tyler expressing her delight and letting him know that she had worn them the previous evening.

Tyler told Karim about the success of the exhibition and thanked him for his help. The jail superintendent now had another proposition for him. During his trip to London, the Queen had discussed the possibility of employing some Indian servants during the Jubilee. She was expecting a number of Indian Princes for the celebration and felt she could do with someone to help her address the Indians presented to her.3 Tyler felt he had just the person for her. He then asked Karim if he would like to travel to England to be the Queen’s orderly during the Jubilee celebrations the following year.

Karim was dumbstruck. He had expected a promotion, but not of this scale. To travel the seas to the Mother Country and personally serve the Queen was a dream come true. He looked at the portrait of Queen Victoria on Tyler’s office wall, sitting on the throne in all her glory and felt a sudden rush of adrenalin, before accepting the offer. It was decided there and then that he would journey to England on a year’s leave of absence.

Karim had understood the word ‘orderly’ in the Indian context, which means a person who accompanies the sovereign or other person of high rank on horseback. It was a higher position than that of an orderly in the British army, who was a private soldier attending his officer. ‘It was in the former sense of the word that I accepted the proposal to go to England,’ wrote Karim, not aware then that he would be required to wait on the Queen, not ride splendidly behind her on horseback.

What followed was a hectic period for Karim as he was trained in English social customs and etiquette....