![]()

1

Macintosh Myths

Allegories for the Information Age

When Steve Jobs introduced the Macintosh computer in a California auditorium in 1984, he looked more like a university professor than a hippie turned computer impresario. Dressed in a green bow tie and dark blazer, he announced to the audience, “All the images you are about to see on the large screen will be generated by what’s in that bag.” In a grandiloquent gesture, Jobs pulled a small diskette from his jacket pocket to cheers from the audience. The song “Chariots of Fire” played over the loudspeakers as the word “MACINTOSH” scrolled slowly across the screen to wild cheers from the audience.

What a strange spectacle: the antics of a quirky computer salesman and the graphics of a nine-inch monochrome display whipping an audience of thousands into a frenzy. The moment was a testament to Jobs’ infectious enthusiasm. It also signaled a paradigm shift in computing. The Macintosh launch reimagined the computer as a tool for creative expression and individual freedom after decades of being a symbol of cold computation.1

Jobs believed that computing was more than crunching code; it was supposed to be an aesthetic and artistic experience as well. Jobs remembered, “I always thought of myself as a humanities person as a kid, but I liked electronics. Then I read something that one of my heroes, Edwin Land of Polaroid, said about the importance of people who could stand at the intersection of humanities and sciences, and I decided that’s what I wanted to do.”2 The images displayed at the 1984 Macintosh launch alternated between sketches of classical architecture and computer code, between spreadsheets and image editing software. The Macintosh married left brain and right brain. In fact, it seemed to have a mind of its own. At one point, Jobs asked the computer to say a few words, and the Macintosh responded with some humorous quips about never trusting a computer you can’t lift (IBM) and how Steve Jobs has been like a father figure to the Macintosh. The machine born during the Cold War had a creative pulse.3

In the course of Jobs’ presentation of the new Macintosh, the screen displayed a photo of Steve Jobs. It was an iconic moment in the introduction of the new computer. At one level, it was merely a way of demonstrating the computer’s graphics capabilities. At another level, it revealed an important dimension of the human-computer dynamic. To see oneself in a creation is the ultimate expression of one’s creative spirit. Jobs, the demiurge of digital culture, was creating technology in his own image and likeness.

Gnosticism in “1984”

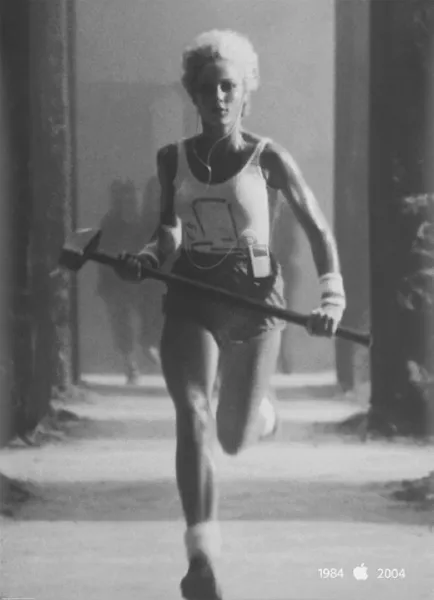

Apple’s early advertising avoided esoteric language about bits and processors and instead focused on constructing a mythical framework for imagining personal computing.4 Apple produced their famous “1984” ad to launch the first Macintosh during the 1984 Super Bowl.5 There are no Macintosh computers in the ad, and the Apple logo does not appear until the very end. Instead, the ad shows a dreary, dystopian science fiction scene in which an army of expressionless drones stare, mouths agape, at a large screen broadcasting an Orwellian rant about ideology and control. The figure on the screen can be interpreted as representing Apple’s competitor IBM. The portrayal is meant to evoke the figure of Big Brother from Orwell’s novel 1984, a not so subtle play on IBM’s nickname, Big Blue. The imposing figure on the screen barks out a caustic monologue:

Today we celebrate the first glorious anniversary of the Information Purification Directives. We have created for the first time in all history a garden of pure ideology, where each worker may bloom, secure from the pests of any contradictory true thoughts. Our Unification of Thoughts is more powerful a weapon than any fleet or army on earth. We are one people, with one will, one resolve, one cause. Our enemies shall talk themselves to death and we will bury them with their own confusion. We shall prevail!

The climax of the ad occurs when a woman, who is being pursued by armed guards, runs into the middle of the assembly and hurls a sledgehammer at the giant screen. The resulting explosion releases a burst of light that washes over the indoctrinated masses while a voiceover reads the text crawl, “On January 24th Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’ ”

The advertisement contrasts a totalitarian vision of technology with the liberating power of Macintosh. Liberation is portrayed as an individual exercise, one performed in the face of great social pressure to assimilate to a dreary, mechanistic mode of existence. The woman is young, strong, and rebellious; an image in sync with the budding feminist philosophies of the mid-1980s that questioned male dominance, especially in the realm of technology.6 Perhaps most striking is the visual of the explosion as the woman’s sledgehammer destroys the screen displaying the ominous male figure. The screen does not explode in typical Hollywood fashion with orange balls of fire and black smoke. Instead, the catastrophic event releases a dazzling torrent of white light that illuminates the darkened hall and transfixes the individuals in attendance. Awakened from their hypnotic state, the men gaze with mouths hanging open, overwhelmed by dread and awe.

Apple commemorative poster, “1984”

seated figures, “1984”

The symbolism of the blinding white light in “1984” provides early evidence of Apple’s propensity to dabble in metaphysical themes when promoting products (see p. 22). Specifically, Apple’s advertising symbolism draws upon a gnostic sensibility. The following passage from gnostic scripture aligns well with the “awakening” scene in the “1984” ad:

They bestowed upon the guardians a sublime call, to shake up and make to rise those that slumber. They were to awaken the souls that had stumbled away from the place of light. They were to awaken them and shake them up, that they might lift their faces to the place of light.7

The female Macintosh revolutionary is a figure for “self-divinization”—a process by which the gnostic, through her own magical and intellectual labor, achieves gnosis, a share in the mind of God. In the mythos of technology, the seemingly infinite body of knowledge offered by the computer puts us in touch with a sense of omniscience.

The polysemous text of the ad also suggests a reading of the cult of drones as the figures in Plato’s cave who have not yet seen the divine light of wisdom, leading them to believe that the shadows on the wall are reality itself. The allegory is especially relevant today. Technology users gaze for hours a day at shadows on the screen. The images on-screen are reflections of reality, but not reality itself. They are digital shadows. For Plato and Socrates, it was contemplation and philosophy that would lead the prisoner to the light. In the Apple mythology, ironically enough, it is the personal computer. It is both the disease and the cure.

In the Western philosophical tradition, Neoplatonic ideas were linked to religious belief systems like Gnosticism.8 Media scholar Erik Davis notes the way in which the rhetoric of technologists bears a distinct gnostic sensibility. In gnostic belief, the material body is a prison and the only way out is to attain the mystical enlightenment that gnosis or divine knowledge provides. The only way to achieve gnosis is to become like the gods and reclaim the divine knowledge lost in the fall. An allegorical reading of the “1984” ad suggests this gnostic ideal in figurative terms. The heroine releases the masses from their material prison by using the giant hammer, a symbol of physical work and toil, as a weapon against the material regime. Her superhuman effort smashes the illusions broadcast by the authoritarian screen and releases the preternatural light.

Strains of Gnosticism can also be found in a reading of the Apple logo itself. The official story is that Steve Jobs worked on an apple commune in the 1970s and felt like it would be a good name for his fledgling computer company. He thought it would minimize the intimidation people felt around computers. When graphic designer Rob Janoff designed the current Apple logo, he added the bite to the side; otherwise, Jobs said it looked too much like a cherry tomato. Those may be the facts of the logo’s creation, but the logo story that has persisted among Apple fans is far more mythological. Given Apple’s penchant for the grandiose, how can one not read the bitten apple as the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil in Genesis?

A documentary about Apple fanatics called Macheads captures a scene where two Apple fans are camping out on a New York City street, waiting in line to buy the new iPhone. Their conversation suddenly turns philosophical as they start to question why they are camping in the midst of New York City in the middle of the night to buy a phone. One gentleman says to the other,

It was eating an apple that caused us as a race of people to be cast out of paradise. So maybe that same knowledge that was so evil early on in mankind’s story remains evil and each time we take a bite of this technological “Apple,” we move further from the garden that was our home and deeper into the hell that is our current want.9

The conventional interpretation of the Genesis account of creation is that Adam and Eve are beguiled by a serpent that tricks them into eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The serpent’s pitch is that they will “be as gods, knowing good and evil.” When they decided to partake, they cursed the rest of humanity with the burden of original sin, punishable by death and suffering. The gnostics read the story differently—in a way that makes for a much less forbidding take on the Apple logo with a bite removed.

According to the gnostics, death and suffering are not humanity’s punishment for disobedience, but rather the state of a world created by a bumbling demiurge. In one of Gnosticism’s sacred texts, the Secret Book of John, it is Christ who enters the garden, plays the part of the serpent, and offers the divine knowledge. By partaking, humans achieve gnosis and share in the divine knowledge.10 Biting the apple was an act of liberation, not an occasion for condemnation. The rest of human history then is the story of those who attain the secret knowledge and those who do not.

Technology presents a similar dualism. There are the haves and have-nots—those who have access to technology and those who do not. There are the enlightened individuals who imbibe the creative spirit of Apple and the ignorant masses who choose otherwise and remain in the soulless dark. The symbol of the omniscient mind fits squarely within the information technology mythology. For Apple, the symbolism could not have been more ripe. Apple’s implicit allegory about computers offering a secret knowledge appeals to a society in which self-actualization is tied to technological sophistication.11

In 1984 it would have been hard to predict the extent to which personal technology would transform the social and cultural landscape. Apple’s over-the-top cinematic take on the coming revolution proved to be prescient. Computers shape daily interactions, from education to entertainment to shopping to banking to socializing. More important, computers shape “mental life.”12 For centuries, books had shaped the interior or mental life, objects that when opened speak of another consciousness, a rational being who communicates thoughts, ideas, and images to the engaged reader. The reader enters the book, and the book enters the reader.

Computers utilize metaphors of the page to encourage familiarity and ease of use. Eminent computer scientist and former Apple employee Alan Kay said this about the computer interface:

By moving the page from book to screen, a new dynamic emerges: the screen as “paper to be marked on” is a metaphor that suggests pencils, brushes, and typewriting . . . . Should we transfer the paper metaphor so perfectly that the screen is as hard as paper to erase and change? Clearly not. If it is to be like magical paper, then it is the magical part that is all important.13

Unlike the page, the screen interface is one of illusion—an ephemeral grouping of electrons that can change or disappear at any moment. The intimacy of interacting with the sensory elements of the printed page, the combed texture, the smell of aged pulp, the crinkling of paper, is absent. As such, the “mental life” fostered by computers is one of fleeting relationships and sensory deprivation. It suggests an entirely different way of thinking about our relationship to the thoughts and imagination of others.

Enlightened Beings

The subtle changes in mental life that followed the adoption of personal computers were not lost on Steve Jobs. In fact, he staked Apple’s future on two words that reflected the changing environment, “Think Different.” Like most creative spirits, Jobs had a mercurial disposition, and his harsh management style became untenable for a company that was seeking stability. After a series of major disagreements with Apple management in the mid-1980s, the tempestuous Jobs spent a decade in exile while the company he founded lost its creative soul. Jobs’ Odyssean return to Apple in 1997 signaled a rebirth for the moribund company.

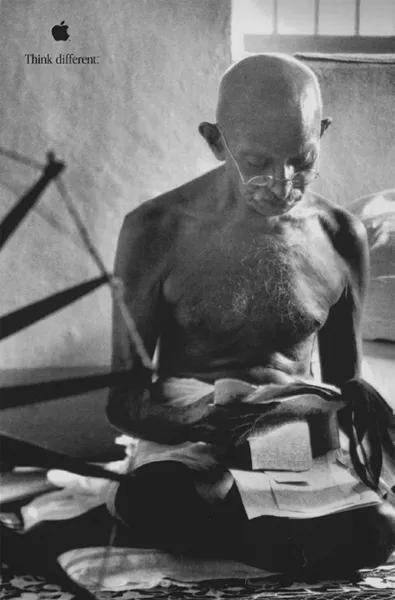

To commemorate Jobs’ heroic return, the company launched the “Think Different” ad campaign (see facing page for an example). The campaign featured famous personalities who captured the Apple spirit of rebellious creativity. The wistful montage of black and white images in the television ad included Albert Einstein, Bob Dylan, Gandhi, Ted Turner, Picasso, and Muhammad Ali, among others. According to the ad copy, they were the misfits, rebels, and troublemakers who also changed the world. They were the “crazy ones” whose ability to think differently was the mark of genius. The ad was a manifesto for Apple’s values.14

“Think Different” ad campaign

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs...