![]()

I

A KEY INTO THE LANGUAGE OF

ROGER WILLIAMS

Cracking and Interpreting

the Roger Williams Code

Around 1680, in the twilight of his life, Roger Williams picked up his polemical pen once again to sketch out his last major treatise.1 Because paper was scarce, he selected a book from his library, flipped to a section with blank space in the margins, and began to write in a shorthand script that he had learned as a young boy.2 The resulting marginalia essay never made it into print, however. Williams died in 1683, and the mysterious scrawl with its irregular strokes remained undeciphered and the essay’s meaning hidden to the world.

In the past, various scholars have attempted to decipher this script, yet it remained an enigma until recently. In the fall of 2011, a team of undergraduate researchers at Brown University, supported and advised by an interdisciplinary group of scholars, came together to undertake the ambitious project of cracking the code and translating the marginalia.3 In early 2012 one member of the team, using a combination of statistical attacks and paleographic clues, cracked the code.4 Soon thereafter, historical evidence confirming Williams’ authorship was uncovered.5 The decoding revealed an entirely new essay by Williams, the contents of which were previously unknown.

Williams’ shorthand essay was part of an ongoing early modern Protestant theological debate between those who believed the Bible supported the baptism of infants and those who opposed it on the grounds that believer’s baptism was the only biblically defensible position. Jumping into a pamphlet war that was already underway,6 the English Baptist minister John Norcott in 1672 wrote a defense of believer’s baptism titled Baptism Discovered Plainly and Faithfully, According to the Word of God.7 The book proved to be immensely popular; it was reprinted in 1675, 1694, 1700, and almost a dozen more times in the following century, with reprintings continuing into the twentieth century in several additional languages.8 A copy of Norcott’s treatise fell into the hands of John Eliot, the Roxbury, Massachusetts, minister and well-known missionary to New England Natives, who in 1679 published a pointed rebuttal of Norcott’s views, titled A Brief Answer to a Small Book Written by John Norcot Against Infant-Baptisme (1679).9 Eliot’s book clearly provoked the elderly Roger Williams, for some time after reading Eliot’s A Brief Answer, Williams sat down and produced a draft in his modified shorthand of a point-by-point refutation of Eliot’s defense of infant baptism, titled “A Brief Reply to a Small Book Written by John Eliot.”10

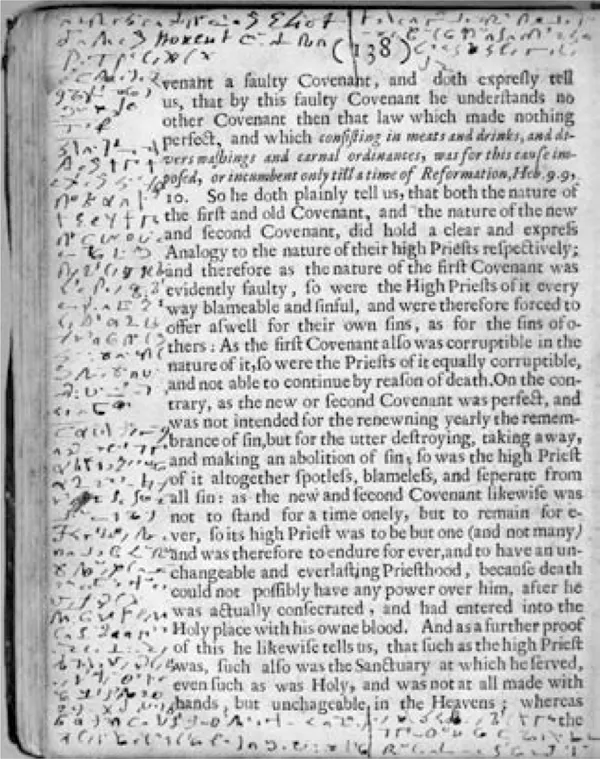

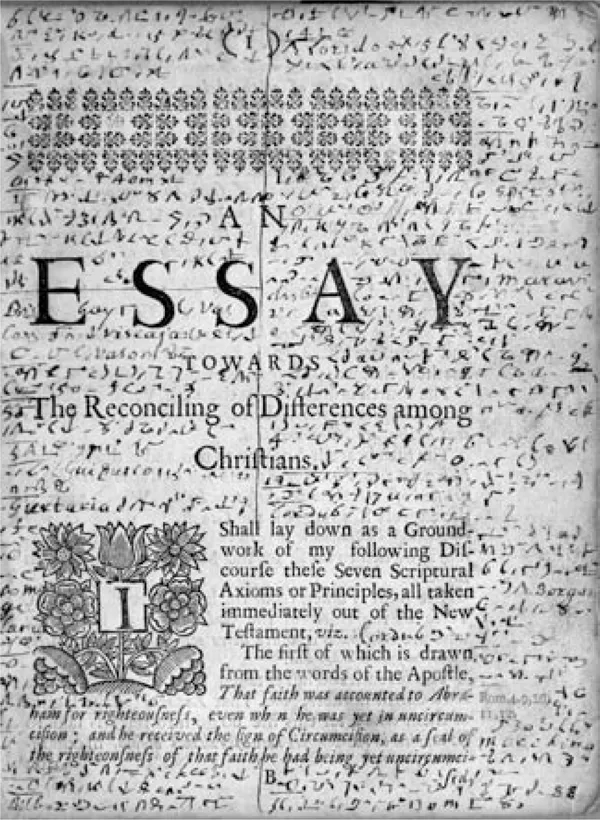

FIGURE 1

Sample of Roger Williams’ shorthand. Taken from An Essay Towards the Reconciling of Differences Among Christians, p. 138.

Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

In many ways, it is unsurprising to find Williams inserting himself into yet another theological controversy, since he devoted his life to defending the principles he believed in, no matter how unpopular these were among his ministerial colleagues and government authorities. Williams (ca. 1603–1683) was born and raised in London, where in his teen years he came to the attention of England’s great seventeenth-century jurist Sir Edward Coke. He became the amanuensis of Coke in his dealings with the king and the courts. Educated at Pembroke College, Cambridge, Williams increasingly sympathized with Puritans and Separatists who sought to reform more fully the Church of England. Under growing pressure to conform more completely to the religious practices of the Church of England (in particular, the use of the Prayer Book), in December 1631 Williams joined a growing stream of Puritan-and Separatist-minded ministers heading for New England. Upon arriving in Boston, Williams immediately clashed with local religious and civil authorities over the issue of separation from the Church of England. During the following four years, he challenged leaders about the propriety of civil magistrates exerting power over spiritual matters and the legitimacy of the king’s land grants for Native lands. Williams’ refusal to acquiesce culminated in October 1635 with his trial and banishment. He fled south to the Narragansett Bay in February 1636 and founded Providence that spring.

Williams’ religious views and church affiliations evolved during his first decade in New England. In the years following his departure from Massachusetts, he was briefly a “Baptist,” during which time he gathered the first Baptist church in the New World in 1638, in Providence, Rhode Island. In 1643 Williams traveled to London to secure a patent for “Providence Plantations in Narragansett Bay in New England,” which scholars have often seen as the first completely secular government in modern history. While in England he published his most popular book, A Key into the Language of America (1643), a book about New England Natives for which he was widely known and admired in his lifetime. Before returning to New England, Williams published The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644), which provoked immediate outrage at the time but garnered the admiration of later generations. For the rest of his life, he was almost continually engaged in the governance of the colony and the town of Providence. Williams generally had good relations with local Native groups and worked hard to keep the peace with them for nearly forty years. Unlike John Eliot, the missionary-minister from Roxbury, Massachusetts, Williams did not encourage or pursue a comprehensive evangelization program among the Natives in his colony.

FIGURE 2

Portrait of Roger Williams. Drawn by C. Dodge in 1936 from a bust of Roger Williams in the Hall of Fame for Great Americans at Bronx Community College. Williams is presented accurately here as a Puritan, with plain clothes and a “Roundhead” haircut. Reproduced with permission from the First Baptist Church in America.

One of the greatest disappointments in Williams’ life was King Philip’s War (1675–1676), which saw the fiery end of his efforts to maintain peace with local Natives.11 The United Colonies (Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut) brought the war to Rhode Island by launching a bloody preemptive attack on the Narragansetts in their fortress in southern Rhode Island in December 1675.12 The war then spread across the colony (except Aquidneck Island) and resulted in the destruction of all colonial settlements on the west side of Narragansett Bay. Native bands burned Providence on March 29, 1676, including Williams’ home, resulting in the loss of unknown numbers of books, documents, letters, and sermons. The aged Williams found himself in a new role, serving as a cocaptain of the Providence town militia and, after the war, chairing a committee that assigned various lengths of servitude to captured Natives to compensate for damages.13

Williams published many significant tracts and treatises during his lifetime, many of them with a polemical purpose in mind. In addition to a lengthy series of printed exchanges with Boston minister John Cotton in the 1640s and 1650s, Williams also published a book against the Quakers (with whom he disagreed, even as he believed in their rights to full religious freedom) in 1676 titled George Fox Digg’d out of his Burrowes. Williams kept up a vibrant correspondence with a wide variety of people in New and Old England. “A Brief Reply” is the last substantial piece of writing we have from Roger Williams. It was written late in his life, sometime between 1679 and 1683, and symbolizes his role—even in its unpublished form—as a controversialist in the wider world of English Protestantism.

CRACKING THE CODE

Roger Williams’ Shorthand System

The volume that contains the Roger Williams code is itself a mystery. It was donated to the Brown family in 1817 by an unknown “Widow Tweedy.”14 The book, now housed in the archives of the John Carter Brown Library, is without a title page. Its title, author, and year of publication remain unknown. The first page of printed text (immediately following the front matter) bears the heading “An Essay Towards the Reconciling of Differences Among Christians,” which scholars have occasionally cited as the title of the book itself; in reality, it was probably a subtitle.15 Virtually every square inch of margin space on the book’s 234 pages has been filled with cryptic shorthand writing, long presumed to be the work of Roger Williams.16

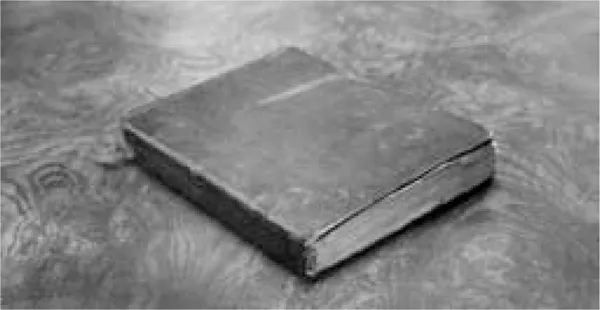

FIGURE 3

External view of An Essay Towards the Reconciling of Differences Among Christians. A photograph of the book that holds the Roger Williams shorthand, housed at the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Photograph by Linford D. Fisher.

FIGURE 4

Title page of An Essay Towards the Reconciling of Differences Among Christians. The shorthand is divided into two columns by a long vertical line. These columns are further subdivided into paragraphs by short horizontal lines. The shorthand on this particular page was transcribed from the chapter in Peter Heylyn’s Cosmographie pertaining to the history, culture, and geography of Spain. A perceptive reader will notice over a dozen longhand terms interspersed throughout the marginalia, including “Biscay,” “Vascons,” “Bilbo,” “Loredo,” and others. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Cracking the Roger Williams code involved a combination of rudimentary cryptanalysis and historical detective work. The first attempts to decipher the shorthand began with a series of statistical analyses. For the kinds of simple substitution ciphers one would expect from the colonial era, a technique known as frequency analysis usually suffices. Frequency analysis looks at the relative frequency of cipher characters to establish a tentative key or correspondence. For example, one might reasonably conjecture that the most frequently occurring symbol in the Roger Williams shorthand corresponds to the English letter “e,” since “e” is the most frequently occurring letter in the English alphabet. Similarly, one might conclude that the second most frequently occurring character in the Roger Williams shorthand corresponds to the English letter “t,” since “t” is the second most frequently occurring English letter. Of course, frequency analysis only works for the simplest sorts of ciphers, since it presupposes a straightforward one-to-one correspondence between code symbols and English letters. If the cipher is any more nuanced than a direct substitution, frequency analysis is of little practical use. Such was the case with Roger Williams’ shorthand.

Crucial insight was gained into the structure of Williams’ shorthand by looking closely at the biography of Roger Williams and th...