![]()

PART I

THE GUILDS

On the head of the ship in the front which mariners call the prow there was a brazen child bearing an arrow with a bended bow. His face was turned toward England and thither he looked as though he was about to shoot.

Roman De Rou, Maistre Wace1

NOTE

1 The Roman De Rou, a verse history of the Dukes of Normandy commissioned by Henry II, was based on oral traditions passed on through the family of Maistre Wace. Here, Duke William leads his invasion fleet to Hastings.

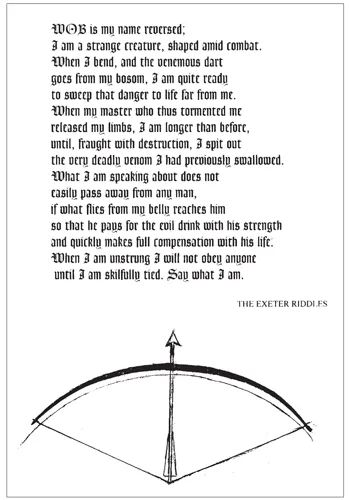

Some bows from the Mary Rose were in good enough condition to be tested like this one (from a photograph). Ascham really meant the arc of a circle when he wrote that a bow should come round compasse.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

… a bow of yew ready bent, with a tough tight string,

and a straight round shaft with a well rounded nock,

having long slender feathers of a green silk fastening,

and a sharp-edged steel head, heavy and thick and an

inch wide, of a green blue temper, that would

draw blood out of a weathercock …

Iolo Goch (bard to Owen Glendower)2

It has been said that archery is about two sticks and a string. That is quite true of mediaeval European archery, but we shall see that there is much more to it than that.

The origin of the longbow is unknown, although some British historians give it a Welsh pedigree. However, early examples have been found throughout Europe, such as those in Danish bog finds, dated to the Roman period. Similarly, Ötzi the Iceman (a mummy discovered in the Ötzal Alps on the border of Austria, and dated to 5300 years ago) had with him a 713/4-inch D section yew longbow and 321/4-inch taper arrows with three-vane glued and bound fletching. The arrows were – in length, materials and workmanship – nearly identical to those issued to archers on Henry VIII’s carrack, the Mary Rose, except that Ötzi’s arrowheads were of chipped stone rather than forged steel and his bow lacked the optional horn nocks. To further confuse matters, in France during the Hundred Years War, the longbow was called the ‘English bow’.

The history of the bow and the longbow in particular is also the history of the wars of mediaeval England. Under King Edward I ‘Longshanks’, archery butts were ordered to be constructed and units of archers and crossbowmen were used during the wars in Wales and Scotland, in which Welsh mercenary archers were employed. A patent roll listed arrows an ell long with steel heads and four strings to each bow, a length indicating that they were to be used with longbows.

Military archery reached its furthest development when employed by English armies during the Hundred Years War with France. With a much smaller population than France, England could not put enough knights in the field to prevail, and had to arm its peasantry. The practical possibilities were pikes, staff weapons, crossbows and handbows. Having experienced the effectiveness of longbows in their local wars, the English chose these rather than the slower shooting and more expensive crossbows that had previously been the missile weapon of choice. But already by 1363, King Edward III complained that that the art of archery had become almost totally neglected, and demanded that everyone practise with bow and arrow or crossbows or bolts and avoid other games.

The military importance of archery, especially in mediaeval England, was such that a complex culture grew around the procurement of materials, and the manufacture and use of archery gear when archers usually outnumbered men-at-arms in English armies by three or four to one and sometimes by as much as ten to one. In hunting also, archery was more favoured in England than elsewhere, and more statutes concerning archery were proclaimed than in other kingdoms. With the end of English military archery during the reign of Elizabeth I, only vestiges of that culture remained. A late use of English military archery was during a moonlight raid by Sir Francis Drake’s men on Nombre de Dios, a Spanish town in New Spain (the West Indies).

In the Market place the Spaniards saluted them with a volley shot; Drake returned their greeting with a flight of arrows, the best and ancient English compliment, which drave their enemies away.

This first part of With a Bended Bow will deal with the manufacture of bows, arrows, and sundry gear as produced in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

NOTE

2 Iolo Goch’s description makes it clear that in his time Welshmen had come to use bows of yew and used broadheads in combat.

![]()

1

THE ARTILLERS

If you come into a shoppe and find a bowe that is small, long, heavy and strong, lyeing streyght, not windyng, not marred with knot, gaule, wyndeshake, wem, freate or pynche, bye that bowe of my warrant.

Roger Ascham, Toxophilus3

To grow in the hall

did Jarl begin.

Shields he brandished

and bow strings wound.

With bows he shot

and shafts be fashioned.

Arrows he loosed

and lances wielded.

Rigsthula4

In the early Middle Ages, archers probably made most of their own gear, and even a Viking jarl (earl) is described as doing so in the Rigsthula. In fact, Vikings of rank prided themselves on doing their own blacksmith work. By 1252 the Assize of Arms of Henry III required English freemen to own and use bow and arrows, and those of a certain income were also to have a sword, dagger and buckler. In the following year villeins and serfs were included, military age being specified as 16 to 60. The Winchester Statute of 1275 required all males under a certain rank to shoot from the age of seven. The outcome of these acts was a great deal of business for artillers, the collective name for those who manufactured bows and arrows.

Such was their importance to the country’s security, the artillers of thirteenth-century Paris were exempt from watch duty on the city walls along with other guilds of craftsmen who directly supplied knights. At that time the same guild made both bows and arrows. In England The Worshipful Company of Bowyers of London were granted the right to wear liveries in 1319. The fletchers, or arrow makers, properly titled ‘The Worshipful Company of Fletchers of London’, formed a separate guild in 1371 and were granted liveries by King Henry VII. After the separation, a bowyer who sold arrows was subject to legal penalties, as was a fletcher who sold bows. Fletchers were however permitted to have three or four bows for personal use, as was expected of every man. In 1416 The Ancient Company of Bowstringmakers was established, although the longbow stringmakers soon formed a separate guild. They and the arrowsmiths seem to have been the poor relations among the guilds that manufactured artillery, and were not granted arms until much later. The names of the guild members often hinted at their profession; ‘Flo’ was once a common term for an arrow and thus men called John le Floer or Nicholas le Flouer would likely have been involved with arrow making.

The artillers supplied English citizens legally required to possess bows and arrows, as well as filling military contracts of livery (military) equipment for the crown. In this time of extreme division of labour, the well equipped archer required the services of five or more different guilds.

The guildsmen both made their product and sold it to the public in their own open fronted shops, usually located in specific areas with others of their company; Ludgate in London became known as ‘Bowyerrowe’. In the morning a pair of horizontal wooden shutters would be opened. The upper one supported by two poles formed an awning while the lower one, supported on two legs, served as a counter. The craftsman and an apprentice worked in full view of prospective customers. At nightfall he retired to his residence above the shop and the shutters were locked and bolted; the guilds discouraged working at night.

The craft guilds acted much like modern trade unions. They restricted membership to guarantee full employment at decent wages to provide a fair return to all. They provided for members who were unable to work, held a local monopoly on their product and prohibited underselling below a fixed price. As no one had an advantage over another guildsman, innovation in tools or techniques was discouraged as well as claims of product superiority.

Employing extra apprentices, one’s wife or young children was discouraged and thus product standards were theoretically maintained, although Ascham (author of England’s first book on archery, Toxophilus) had some complaints on this score, criticising ‘hastiness in those who work ye kinges Artillerie for war thinkynge yf they get a bowe or a sheafe of arrowes to some fashion, they be good ynough for bearynge gere.’ There were other complaints as artillers had increasing difficulty in getting suitable wood and other materials. In 1385 a seller of false bowstrings was put into a London pillory and the bowstrings burned under his nose. In 1313 bowyers were accused of using poor wood, and in 1432 there were complaints about fletchers using green wood and working at night, which had been forbidden in 1371.

Each year a ‘Warden of the Misterie’ was chosen to oversee the guild and ensure that the ordinances (rules) were observed. The misterie was learned during an apprenticeship that would last from seven to ten years, after which the apprentice would be declared free or sworn of the city, when he would have the right to open his own shop and take on apprentices. While nearly all guild members were men, at least one female bowyer is recorded.

Some guilds and guild leaders amassed considerable wealth. The Worshipful Company of Fletchers of London still exists, although unsurprisingly it no longer has anything to do with the manufacture of arrows. Today it manages property and investments left over from the functional days of the guild.

Once a year the guildsmen held a great feast; a description of one from the time of Henry IV gives an impression of the sumptuousness and bizarre theatricality of mediaeval catering. The hall was hung with hallings of stained worsted and birch branches and the floor was covered with mats or rushes. When all had washed and wiped themselves the feast began with good bread and brown ale.

Then came the bruets, joints, worts, gruel ailliers and other pottage, the big meat, the lamb tarts and capon pasties, the cockentrice or double roast, (griskin and pullet stitched together with thread) or great and small birds sewed together and served in a silver posnet or pottinger, the charlets, chewets, callops, mawmenies [spiced chicken], mortrews [meat in almond milk] and other such entremets of meat served in gobbets and sod in ale, wine, milk, eggs, sugar, honey, marrow, spices and verjuice made from grapes or crabs [crabapples]. Then came ...