- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

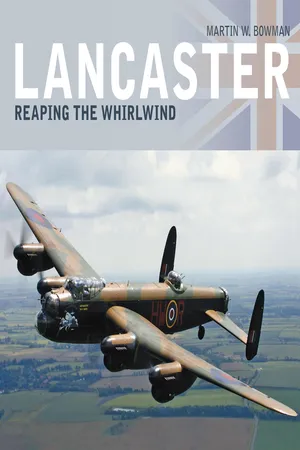

Detailing the Lancaster's history from 1942–45, this study brings everything together to tell a concise history of the world's most famous aircraft of all time and undoubtedly the finest bomber of the Second World War. A superlative and unique colour section of over fifty contemporary photographs of the Lancaster is featured, while the text is complemented by over 150 rare and seldom seen black and white images. Well researched and expertly written, this account is a must read to those interested in the Lancaster and aviation history in general. The book also includes many unique and incredible eyewitness accounts of the raids by Lancaster crews, making Lancaster: Reaping the Whirlwind both a gripping and fascinating read.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lancaster: Reaping the Whirlwind by Martin W. Bowman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & World War II. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

NOT A CLOUD IN THE SKY

The Lancaster, coming into operation for the first time in March 1942, soon proved immensely superior to all other types in the Command. The advantages it enjoyed in speed, height and range enabled it to attack with success targets that other types could attempt only with serious risk or even certainty of heavy casualties. Suffice it to say that the Lancaster, in no matter what terms, was incomparably the most efficient of our bombers. In range, bomb-carrying capacity, ease of handling, freedom from accident and particularly in (low) casualty rate, it far surpassed the other heavy types.

Sir Arthur Harris

On Christmas Eve 1941 three ex-works Avro Lancasters arrived at Waddington – a magnificent Christmas present for 44 Squadron, which in September had become ‘Rhodesia’ Squadron because of the considerable number of Rhodesian volunteers now serving on it, many awaiting air-crew training. ‘The Rhodesians – with their outlandish appearance and air of tough independence, skins bronzed by a warmer sun than England’s and eyes used to wider distances – were so unmistakably not English,’ recalled Pip Beck, a WAAF. ‘I liked their easy, pleasant manner and lack of formality and soon came to know them well. The men came from places with strange musical names. Shangani, Umtali, Gwelo, Selukwe – Que-Que, Bulawayo – one could almost make a song from them, I thought.’ It was with intense interest that everyone in Flying Control watched the Lancasters’ approach and landing. As the first of the three taxied round the perimeter to the Watch Office, Pip Beck stared in astonishment at this ‘formidable and beautiful’ aircraft, cockpit as high as the balcony on which she stood, and the great spread of wings with four enormous engines. ‘Its lines were sleek and graceful,’ she purred:

yet there was an awesome feeling of power about it. It looked so right after the clumsiness of the Manchester, from which its design had evolved. Their arrival meant a new programme of training for the air and ground crews and no operations until the crews had done their share of circuits, bumps and cross-countries and thoroughly familiarised themselves with the Lancasters. There were one or two minor accidents at this time; changing from a twin-engined aircraft to a heavier one with four engines must have presented some difficulties – but the crews took to them rapidly. I heard nothing but praise for the Lancs.

Snow blanketed the airfield and blew into great drifts. It was very beautiful to look out on from the Control room, wearing my loaned flying boots – but less enjoyable to walk through when the blizzard raged. When it stopped, all hands were called out to help clear the runways and it was an amazing sight to see hundreds of airmen, aircrew and some WAAFs shovelling away until well into the dusk to free the main runway. Between the efforts of the snowploughs and the toiling shovellers, piles of snow lay by the sides of the runway and the job was done. A little flying took place and two of the precious Lancs suffered a small amount of damage, though not serious, in spite of the dreadful weather conditions.

The weather eased up a little and one day the airfield seemed to be overrun with boys from the Lincoln Air Training Corps. I watched enviously as they had trips in a Lanc. If they could have this marvellous opportunity, why couldn’t I? It was expressly forbidden for WAAF to go up in operational aircraft. The boys were wildly enthusiastic, of course …1

The Rhodesian Squadron would suffer the heaviest overall losses in 5 Group and the heaviest Lancaster losses and highest percentage of Lancaster losses both in 5 Group and in Bomber Command. But they operated Lancasters longer than anyone else and they were the only squadron with continuous service in 5 Group.

Coinciding with the introduction of the Lancaster into squadron service was the arrival on 22 February 1942, at Bomber Command Headquarters at High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, of a new AOC-in-C, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Travers ‘Bomber’ Harris CB OBE, who was recalled from the USA where he was head of the permanent RAF delegation. Harris was directed by Marshal of the RAF Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff, to break the German spirit by the use of night area rather than precision bombing and the targets would also be civilian, not just military. The famous ‘area bombing’ directive, which had gained support from the Air Ministry and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, had been sent to Bomber Command on St Valentine’s Day, 14 February, eight days before Harris assumed command.

Roy Chadwick, Chief Designer of the Lancaster, in his office at Avro. Born in Farnworth near Bolton in 1893, Chadwick began work in the drawing office in 1911, and in 1936 he designed the Manchester twin-engined bomber to specification P.13/36. When, by mid-1940, he knew that the bomber would not prove successful, he instructed his design staff to convert the Type 679 to a four-engined bomber using either Rolls-Royce Merlins or Bristol Hercules radials and the Lancaster was born. Unlike Reginald Mitchell, designer of the equally illustrious Spitfire, Chadwick witnessed the fruits of his endeavours during the war but he was killed on 23 August 1947 in the crash of the Avro Tudor II during a test flight.

Harris did not possess the numbers of aircraft necessary for immediate mass raids. On taking up his position he found that only 380 aircraft were serviceable. Of these, only 68 were heavy bombers, while 257 were medium bombers. Another of the new generation RAF bombers, the Manchester, had been suffering from a plague of engine failures and was proving a big disappointment. During March, 97 ‘Straits Settlements’ Squadron moved the short distance from Coningsby to Woodhall Spa, south-east of Lincoln, to become the second squadron to begin conversion from the Manchester to the Avro Lancaster. On 36 raids with Manchesters, 97 Squadron had lost eight aircraft from 151 sorties. Re-equipment would take time and early in 1942 deliveries began to trickle through. In January–February, 44 Squadron’s Lancasters and their crews spent a frustrating time standing by to fly to Wick in Scotland to refuel and take off again to sow mines at the mouth of a Norwegian fjord to prevent the Tirpitz from sailing, but the weather worsened and the Lancasters remained on the ground. On 23 February, the Lancasters were again loaded up with mines but the aircraft stood by all the next day and then were stood down until 1 March. Finally, on the evening of 3 March, with AVM John Slessor, the 5 Group commander, there to watch them, four aircraft led by S/L John Dering Nettleton, the South African CO of 44 Squadron, took off and flew the first Lancaster operation when they dropped mines in the Heligoland Bight. All the Lancasters returned safely. That same night the Main Force destroyed the Renault factory at Billancourt, near Paris. Just one aircraft (a Wellington) was lost. During March also, the first ‘Gee’ navigational and target-identification sets were installed in operational bombers; these greatly assisted aircraft in finding their targets on the nights of 8/9 and 9/10 March in attacks on Essen. Without ‘Gee’ these had been a difficult target to hit accurately. Just two Lancasters took part in the second of the Essen raids because on 8 March eight of 44 Squadron’s Lancasters had been ordered to Lossiemouth for a possible strike on the Tirpitz near Trondheim. ‘A Naval convoy escort fired at the Lancs as they flew over it,’ recalls Pip Beck. ‘A Spitfire next attacked the Lancs until frantic firing of the colours of the day convinced its pilot that they were not enemy aircraft.’ Luckily no damage or casualties had resulted beyond irritated and indignant air crew. ‘Oh well – the bloody Navy doesn’t know its aircraft from its elbow! But they expected better from their own Service. If words could kill, the Spit would have gone down in flames.’

By command of the Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe, the staff of the Luftwaffenbefehlshaber Mitte (Luftwaffe Reich or German Air Force Command Centre) had been set up in March 1941, and the following month the night-fighter division, under Generalmajor Josef Kammhuber, was placed in its command. In Holland and the Ruhr 6–10/10ths cloud was quite customary, so Kammhuber therefore concentrated his energies on the development of an efficient Ground Controlled Interception (GCI) technique – Dunkle Nachtjagd – later called Himmelbett (literally ‘bed of heavenly bliss’, or ‘four-poster bed’, because of the four night-fighter control zones). Kammhuber arranged his GCI positions in front of the searchlight zones and encouraged crews to attempt interception first under ground control; if that failed, the searchlights were then at their disposal. By the winter of 1941–42, the Kammhuber line was complete. The night-fighter formations, equipped mostly with Bf 110s, were stationed almost entirely in Holland, Belgium and north-western Germany. The completion of night-fighter bases for controlled Himmelbett fighting, with two giant Würzburgs and one Freya radar, progressed well and was planned to cover initially the north German coastal area and Holland, and later Belgium.

The first Lancaster night-bombing operation on a German target was inauspicious. Only 62 of the 126 Main Force crews dispatched claimed to have bombed Essen, which was obscured by unforecast cloud and industrial haze. Both of 44 Squadron’s Lancasters returned safely, though one was hit by flak and the other had to land back at Docking in Norfolk. On the night of 13/14 March 1942, a single Lancaster piloted by Sgt George ‘Dusty’ Rhodes joined 61 Wellingtons, 13 Hampdens, ten Stirlings, ten Manchesters and nine Halifaxes in bombing Cologne. Rhodes got into difficulties on the return and landed without runway lights, overshooting the airfield. On 20 March, the second Lancaster squadron, No 97, flew their first operation with six aircraft out mining along the coast of Ameland and the Friesian Islands. One of the Lancasters machine-gunned a hotel and a party of soldiers for good measure and then climbed into cloud when a Bf 109 was spotted. All the Lancasters returned but one crashed near Boston and another landing at Abingdon crashed owing to the soft state of the ground. Two others landed safely at Upper Heyford and one at Bicester. On another mining operation, off Lorient on the night of 24/25 March, the first Lancaster casualties occurred when R5493 failed to return. A 420 Squadron RCAF pilot reported that he had seen a four-engined bomber heavily engaged with anti-aircraft (AA) fire over Lorient and the Royal Observer Corps reported flares out to sea. A search was made but no trace of South African F/Sgt Lyster Warren-Smith’s crew was found.

On 25/26 March, seven Lancasters were included in the force of 254 aircraft, making it the largest force sent to one target so far, when Bomber Command attacked Essen again. Over 180 crews claimed to have bombed the city but the flare-dropping was too scattered and only nine HE bombs and 700 incendiaries fell on target. All the Lancasters returned safely but nine aircraft, including five Manchesters, were lost. Lancasters took no part in further operations until the night of 8/9 April, when the main Bomber Command operation was to Hamburg and 272 aircraft were dispatched, yet another record raid for aircraft numbers to one target. Over 170 Wellingtons and 41 Hampdens made up the bulk of the force, which included just seven Lancasters. That same night 24 Lancasters on 97 Squadron carried out a mine-laying operation in the Heligoland Bight. Two nights later, eight Lancasters were included in the force of 254 aircraft that visited Essen again. Fourteen aircraft were lost but the Lancasters all returned safely.

Post-raid reconnaissance photo of the 17 april 1942 raid on augsburg when 12 aircraft of 44 and 97 Squadrons, led by S/L J.D. nettleton, carried out a low-level daylight attack on the man diesel engine plant. nettleton was awarded the VC for his part in the raid.

Visiting a dispersal at Waddington, Pip Beck noticed on a neighbouring hard-standing a Lancaster with different engines.

‘They,’ I was told, ‘are radial engines – it’s a Mark II Lanc. Our Mark Is have in-line engines which, as you know, are Merlins. The Mark IIs are Bristol Hercules Is.’ I was given some more technical detail, but that didn’t stick. However, at least I could recognise a Lanc with radial engines and say, knowledgeably, ‘Ah yes – a Mark II Bristol Hercules!’ and feel rather smug.

During April, a suspicion grew in Control that something big was being laid on for sometime in the near future and 44 would not be the only squadron involved. There had been frequent visits from S/L Sherwood and F/L Penman on 97 Squadron at nearby Woodhall Spa. Low-level cross-country flight practices were taking place and we wondered what they presaged. On April 17th we found out.

On 11 April, 44 Squadron had been ordered to fly long-distance flights in formation to obtain endurance data on the Lancaster. At the same time 97 Squadron began flying low in groups of three in ‘vee’ formation to Selsey Bill, then up to Lanark, across to Falkirk and up to Inverness to a point just outside the town, where they feigned an attack, and then back to Woodhall Spa. Crews knew the real reason was that they were training for a special daylight operation, and speculation as to the target was rife. S/L John Nettleton was chosen to lead the operation. During the morning of 17 April he and S/L John Sherwood DFC*, the 97 Squadron CO, and selected officers were briefed that the objective was the diesel engine manufacturing workshop at the MAN (Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg Aktiengesellschaft) factory at Augsburg in southern Bavaria. P/O Patrick Dorehill, Nettleton’s 20-year-old second pilot, wrote:

There was certainly some surprise on entering the briefing room to see the pink tape leading all the way into the heart of Germany. I can’t say I felt anxious. I had an extraordinary faith in the power of the Lancaster to defend itself. And then flying at low level seemed to me to be the perfect way to outwit the enemy. I thought the only danger might be over the target and, even there, believed we would be in and away before there was much response.

In the late afternoon a force of 12 Lancasters, flying in two formations of six, set out to attack the MAN works. The Lancasters flew very low. The first flight, led by Nettleton, ran into German fighters when well into France. In the battle which ensued, four of the Lancasters were shot down. Nettleton flew on towards Augsburg. When they got near the target the light flak was terrific and another Lancaster was hit and crash-landed 2 miles west of Augsburg.

Patrick Dorehill continued:

It was only sheer bad luck that we flew past an enemy airfield to which their fighters were returning from the diversionary raids our fighters and Boston bombers had laid on to the North. Up they came and I shall never forget those terrible moments. I do not think there were as many fighters as our gunners reported; it was just that each made several attacks which made it seem like more. Being on the jump seat I stood up and saw quite a bit of the action. Maybe there were a dozen. At any rate I looked back through the astrodome to see Nick Sandford’s plane in flames. He always wore his pyjamas on ops under his uniform. He thought it would bring him good luck.

This was followed by Dusty Rhodes’ plane on our starboard catching fire. The rest went down except Garwell on our port side. There was nothing for it really but to press on. A passing thought was given to turning south and then out to the Bay of Biscay but we reckoned that as we had come so far we might as well see it through. By this time I can tell you I didn’t give much for our chances. On we went and I marvelled at the peaceful countryside, sheep, cattle, fields of daisies or buttercups. Along came the Alps on our right, wonderful sight, Lake Constance looking peaceful. We had climbed up a bit by then, it being pretty hilly, and then down we came again getting close to the target. My recollection may be faulty but I thought we approached Augsburg from the south, following a canal or railway, factory chimneys appeared on the low horizon and then we came to the town. Large sheds were right in our path; Des Sands, the navigator, and McClure, the bomb aimer, had done a pretty good job of map reading.

Bombs away at about a hundred feet.

The flak zipped past and as we crossed the town to begin a left turn for home a small fire was apparent, gradually gaining strength, in Garwell’s plane. Our gunners saw it make a crash landing, which seemed to go relatively well.

The trip home was uneventful, thank goodness … Nettleton did a brisk circuit and down we came to be almost out of fuel. Golly, I can tell you I was glad to feel those wheels touch the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Milestones

- 1 Not a Cloud in the Sky

- 2 The Shining Sword

- 3 Old Man Luck

- 4 Chop City

- 5 Round-the-Clock

- 6 ‘This is War and Somebody’s Got to Die!’

- 7 The Means of Victory

- 8 Lancaster Legacy

- Appendix 1 Bomber Command Lancaster Crew Victoria Cross Recipients

- Appendix 2 Aircraft Sorties and Casualties 3 September 1939–7/8 May 1945

- Appendix 3 Summary of Production

- Appendix 4 Lancaster I Specifications

- Appendix 5 Halifax/Lancaster Comparison at the End of 1943

- Appendix 6 Comparative Lancaster and Halifax Squadrons

- Appendix 7 Lancaster Squadrons at Peak Strength 1 August 1944

- Appendix 8 Lancaster Squadrons Formed Late 1944–45

- Plates

- Copyright