![]()

PART ONE

IN THE GRIP OF THE ICE: THE PALAEOLITHIC

![]()

Chapter 1

ANCIENT RITES IN

AN ANCIENT CAVE

All about us is a landscape of ice and snow; the wind tugs at the furs wrapped around us and the chill grips our bodies like a fist. You gesture to the cave and we move inside. It is strangely lit and we realise with a start that there is a fire towards the rear and large shapes moving around it. They are people, but not like any we have ever seen before. Large, squat, and powerfully built; we catch glimpses of their faces and cannot help but stare at their pronounced noses and brows. We have entered the lair of the Neanderthals. Moving closer, we notice that they are filling a pit with stones and loose earth. They are covering something but we cannot quite make it out. You creep closer still and point to a shape sticking out of the soil. It is an arm; the Neanderthals have just buried one of their dead. All at once there is a low sound that fills the cave; it is mournful but strangely rhythmic. We realise that it is the Neanderthals singing; is this how they lament their dead?

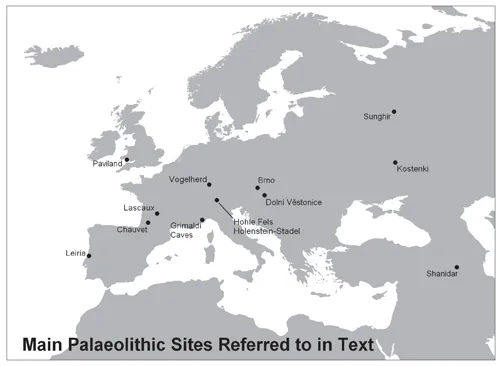

It is difficult to establish when Neanderthals first colonised Europe, as the fossil remains of the earliest examples are difficult to tell apart from earlier species of humans. It was thought that 300,000 years ago was the absolute earliest that Neanderthals had evolved as a separate species but new excavations at Atapuerca, in northern Spain, have suggested that it might be closer to 400,000 years ago, although whether these fragmentary remains are of Neanderthals or of an even earlier species of human is still debated.1 However, from the remains of several individuals found at Ehringsdorf in Germany, and (more securely dated but far scantier in terms of remains), Pontnewydd Cave in Wales, it seems certain that Neanderthals had colonised most of Europe by at least 230,000 years ago.2 They were to last another 200,000 years.

The landscape inhabited by the Neanderthals was one of wildly fluctuating temperatures. Although supremely adapted for the Ice Age, which affected Europe for much of the time that they were around, Neanderthals also had to cope with sudden periods of warming and even, on occasions, sub-tropical environments. During the last inter-glacial period (the warmer period between Ice Ages), between 128,000 and 118,000 years ago, there were even hippos living in southern England. Sudden climate change was nothing new to the Neanderthals and they coped with it remarkably well.3

Although Neanderthals certainly looked very like us, just how human their behaviour actually was is hotly debated, especially when it comes to burial. Caring for the dead is a very human trait since the focus is on the presumed soul of the individual and its journey to the afterlife – concepts requiring imagination and belief, which some think were beyond the reach of Neanderthals. Had we arrived slightly earlier in the cave, we may have witnessed how the Neanderthals had conducted the burial of their dead: whether they had spoken any words to the corpse, whether they had put any offerings in the grave, and whether the body had been laid out with respect. We certainly heard what sounded like singing but was this part of a mourning ritual or just a spontaneous outpouring of grief ? Evidence of Neanderthal burial is tantalisingly scant and these are issues that archaeologists continue to debate.

Although some 500 Neanderthal bodies are known, most are very fragmentary and only around 20 are reasonably whole. Of these, even fewer were buried.4 However, in the few cases where a pit had been dug to hold the body (interpreted as a sign of deliberate action on the part of the survivors) many of the remains were positioned in a foetal position, as if they had been placed with respect. Moreover, at La Ferrassie in France, two bodies were laid head-to-head, perhaps mirroring the relationship the individuals had in life.5

Possibly the most celebrated Neanderthal burials were found within caves at Shanidar, in modern-day Iraq. Rose and Ralph Solecki, a husband and wife team, found several burials between 1953 and 1960, including a man who had been crushed on the right side of his body, perhaps from a rock-fall, leading to partial paralysis and infection. That he lived for several months after the accident shows that the others in the group must have cared for him, and were evidently not thuggish brutes, but it did not prove that they honoured him after death.6 Elsewhere in the cave, a Neanderthal burial was surrounded by flower pollen.7 Could this have come from bouquets left by distraught loved ones? This would have been a typically human gesture to mark mourning and loss, and it would also indicate, as the excavator put it, that Neanderthals had a love of beauty.8 The idea seemed to echo the preoccupation with ‘flower power’ at the time of excavation.

At another Neanderthal burial site at Teshik-Tash in Uzbekistan, a young boy was laid in a cave surrounded by six pairs of horns from local mountain goats.9 The brief lighting of a fire next to the body seems to suggest that maybe this was part of a funeral ritual. At other sites, items appear to have been left with the bodies, perhaps indicating that these were offerings for the deceased to use in the afterlife. Particularly striking were the cattle bones left next to a body at Chapelle-aux-Saints in France.10 If these were once joints of meat, could they have been provisions for the afterlife? Similarly, at Amud, in Israel, a red deer jawbone seemed to have been deliberately placed next to the pelvis of an infant.11 Was there some symbolism associated with this act?

In our cave, we watch as the last stones are placed on the grave and the Neanderthals turn their attention back to the fire. One leans forward and throws another branch to land in its heart. There is a sharp hiss and the flames leap momentarily higher. The Neanderthal nearest the fire is briefly lit and we notice that he is sawing something with a flint knife, holding the item tightly between his front teeth. We also notice a thread around his neck. It is a sinew necklace holding a small shiny object, possibly a shell; the fire has dimmed again and it is difficult to tell. With a start, we realise that the object rests on the swell of a breast. This is a Neanderthal woman! We grin at each other in embarrassment but there is no need to apologise for our mistake. Through the gloom and smoke of the cave, both sexes look remarkably alike.

Wearing jewellery at this time was almost certainly symbolic: it portrayed a message. Could the Neanderthal woman have been saying something about herself? The shell may have marked her out as having travelled to the sea, or that she had relatives in that part of the world. Nevertheless, would the others have understood the message? What this demands is abstract thought, an advanced form of intelligence thought to be held exclusively by modern humans. In effect, the shell stands for so much more than merely a shell; it becomes a metaphor for a host of other ideas and thoughts. To understand it fully requires a degree of comprehension that brings together a variety of disparate ideas and links them with symbolic connections. Could the Neanderthals have done this, or was a shell merely a shell?

However, shell jewellery is not the only evidence for symbolic thought attributed to Neanderthals. Art is usually assumed to be an indication of advanced thought: making something stand for something else. Although the evidence for Neanderthal art is vanishingly small, some claim to have found it. At Berekhat, in Israel, a small figure of what might be a woman was certainly made by Neanderthals, as microscopic analysis of the cut marks demonstrates.12 Elsewhere, at La Roche-Cotard in France, other excavators have claimed that a lump of flint was modified with the addition of a bone splinter to resemble a face.13 As with most art, however, its veracity is most certainly in the eye of the beholder. Although there are no caves that were painted by the Neanderthals, they gathered lumps of pigment, particularly red ochre and black manganese dioxide.14 The most likely explanation is that the pigment was for painting their bodies, although whether this was for decoration or merely to fend off the strong sun is a moot point.

Although we thought we heard the Neanderthals singing, some think that they went further still and actually made musical instruments. Moreover, an appre...