![]()

THE BATTLEFIELD:

WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED?

I stood on the slagheap staring at this curtain of smoke hour after hour, dazed by the tumult of noise and by that impenetrable veil which hid all the human drama. The guns went on pounding away day after day – labouring, pummelling, hammering.

Philip Gibbs, 1933

21–24 September 1915

| 7am | Preliminary bombardment opens on the Loos battle front, continuing until 24 September |

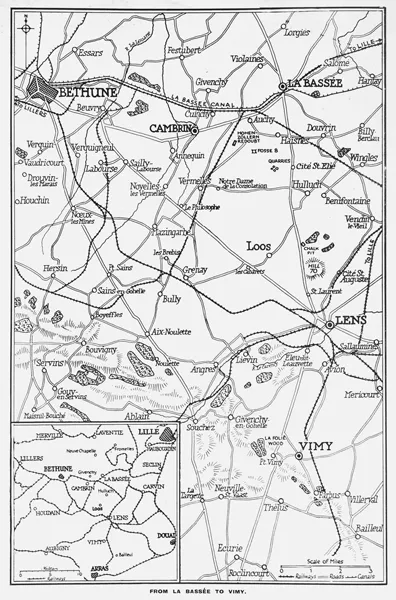

With the battlefield bisected by the Vermelles–Hulluch road, and flanked by La Bassée canal in the north and the Lens railway in the south, the attacks opened on a bright day at zero hour, 6.30am. The bombardment that had continued for four days suddenly fell silent. It was up to the gas to do its job, released forty minutes earlier, and intended to stupefy the enemy.

However, the question of whether gas would be able to achieve what was expected of it literally hung in the air, particularly given the possibility that atmospheric conditions might not match the aspirations of Sir Douglas Haig. If the gas cloud was to form, and was to roll across no-man’s-land with sufficient haste, then wind would be needed, and a steady breeze of 6–8 miles an hour at the very least. Sir Douglas Haig deployed a team of meteorological experts who would be in a position to advise, from Captain E. Gold of the Royal Flying Corps, who received bulletins from the Meteorological Office in London and its equivalent in Paris, to a team of forty gas officers, who were specially trained in wind speed and direction estimation. On their shoulders was the responsibility of advising the GOC First Army; if all was not well, then the attack would stutter. Gas was the central component of Haig’s plan, without it the feeble artillery bombardment would have limited effect. The wind had to be right.

29. Map of the Loos battlefield between Lens and La Bassée.

On 24 September, Haig and his corps commanders met with Gold. There was no chance of a favourable wind that day; but there was the possibility that there would be a breath of wind blowing from the west the following day. Haig grasped the opportunity: ‘The weather forecast … indicates that a west or south-west wind might be anticipated tomorrow, 25th September. All orders issued for the attack with gas will therefore hold good.’ Nevertheless, there was the possibility that the forecast could be wrong. With the assault timed to start at 6.30am, and the gas release at 5.50am, Haig and his staff were understandably nervous when at 5am there was hardly a breath of wind. Then, when his senior aide-de-camp, Major Fletcher, lit a cigarette, the puffs of smoke were seen to drift in exactly the opposite direction. For an expert opinion, Haig consulted with his gas officer, Lieutenant Colonel Foulkes, who confirmed that his men would not turn on the gas taps if there was a chance of the gas hanging close to the British trenches; that coupled with the fact that the breeze picked up from the south-west convinced Haig to commit to action:

FAIL-SAFES

Though Haig was committed to the use of gas, every precaution had been made to stop the release, if conditions or if the local environment were to change. There were telephone links, telegraphs and dispatch riders for higher commands. There were runners ready to pass on details to gas officers. Each of these officers also had typewritten slips of paper bearing the message: ‘attack postponed, taps NOT to be turned on until further notice.’ Foulkes had also provided his officers with the authority not to turn on the gas if local conditions were difficult.

Zero hour arrived at last at 5.50am, and with a redoubled artillery bombardment the gas and smoke were released all along the front … the gas cloud was rolling steadily over towards the German lines … apart from the artillery drum-fire and the clouds of gas and smoke from eleven thousand candles, twenty-five thousand phosphorous hand-grenades were spurting out dense white fumes.

Lt Col C.H. Foulkes, Commanding RE Special Companies

The effect on the Germans was, nevertheless, variable:

The effect of the gas on our men, who were warned in time and who were able to put on their protective outfits, varied with density and the susceptibility of individuals. The smoke allowed some companies to be surprised … the masks then in use broke down under later waves. The formation of rust on the metal parts of the weapons, which had not been observed hitherto, made the guns and machine-guns useless.

War Diary, 6. Armee

25 September 1915: Opening day of the Battle of Loos

| 5.50am | Artillery bombardment of the German trenches along the battle front, in tandem with chlorine gas release |

25 September 1915: IV Corps

Attack on the frontage between Lens and the Vermelles–Hulluch road |

25 September 1915 |

5.50am | Chlorine gas release from cylinders; gas moves slowly towards the German lines in the south (47th Division front), but lingers to the north, in the 15th and 1st Divisional fronts. Gas taps are turned off on the Grenay Spur, the location of the 1st Divisional front, following British gas casualties |

6.20am | Gas taps turned on again; more British gas casualties in the 1st Division |

6.30am | Zero hour, men of the 1/18th Battalion, the London Regiment kick a football towards the German lines; farther north, the Scots of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers are piped out of their trenches by Piper Laidlaw, who would later that day receive the Victoria Cross for his actions. On the 1st Division front, attack is held up in front of Hulluch |

7.30am | Men of the 47th Division in position at the right of the line, securing the Double Crassier |

8am | Men of the 15th and 47th divisions largely clear the streets of Loos of German troops |

9am | Germans regain Bois Carré on the 1st Division front |

9.15am | Men of the 15th Division reach the Lens road |

9.30am | Hill 70 captured; inadvertent change in direction of the attacking troops towards Lens and Cité St Laurent |

10am | Loos village fully in British hands |

10.55am | Composite ‘Green’s Force’ attempts to carry the German lines to the north of the sector by frontal assault; it would be held |

11.30am | German reinforcements at Cité St Laurent push back the advanced British troops |

1pm | German counter-attack carries Hill 70 |

1.15pm | Major General Holland commits his 1st Division to an assault on Hulluch; assault continues for the rest of the day with little result. Hulluch would not fall |

The corps boundary of the Vermelles–Hulluch road would prove to be of the greatest significance in the coming battle. For the IV Corps, south of the road, there would be the greatest initial success; but with the expectation that there would be sufficient reserves to back them up, there was to be nothing left in reserve in the corps itself. The attack would be all or nothing.

30. Topographic map of the IV Corps front, south of the Vermelles–Hulluch road, showing the village of Loos.

The London Territorials of the 47th Division were located in the southern part of the sector adjoining the French, south of the miners’ villages at Grenay known as North and South Maroc, on the outskirts of Lens. It was naturally down to them that the distinctive pit-head gear of the Loos pylons had been nicknamed ‘Tower Bridge’. At this point in the line the topography was more variable, with Grenay and Maroc occupying a spur and the mining village of Loos nestling in a shallow valley, the slopes of Hill 70 beyond. Fortunately, the men of the 47th Division had been trained in the assault on topography similar to this close to Noeux-les-Mines. The Londoners were given the task of capturing the frontline trenches in front of Loos to create a defensive position to the right of the line linking the spoil heaps of the Double Crassier (a double bank of spoil that extended some 1,200yds) to the Loos Crassier (a slagheap that intruded deeply into the village). In order to anchor the whole British advance, these London Territorial battalions were required to hold the line at all costs, preventing the Germans from outflanking the main line of the attack.

The gas cloud was released at 5.50am; given that the gas itself was heavier than air, despite the insignificant breeze, the chlorine was to hug the contours as planned and flow as a yellowish-green cloud downslope towards the village. At 6.30am, covered by a thick smoke barrage supplied by Stokes mortars, men of the division were to rise from their trenches or emerge from shallow Russian saps and advance down the slope in full view of the German trenches; it was essential that the gas and preliminary bombardment do their job. To confuse the Germans, dummies had been placed in no-man’s-land in order to draw fire. At first, it seemed that the German defenders were going to put up a stiff fight: there was wild machine-gun and rifle fire from the firesteps of the enemy trenches. This would soon change in the face of determined attacks by the Territorials between the two crassiers and the Loos–Bethune road.

31. Men of the 47th Division advance forward on the morning of 25 September.

The men of the London Irish Rifles (1/18th Battalion, London Regiment), on the left of the 47th Division line, north of the Double Crassier, would be first out of the trenches. The battalion was famous for footballing prowess, its team roundly beating others of the brigade, so it was perhaps not surprising that their entry into the ‘big push’ would involve kicking leather footballs forwards towards the German trenches. Officially frowned upon, one man,...