eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Fractal Architecture

Organic Design Philosophy in Theory and Practice

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 420 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Throughout history, nature has served as an inspiration for architecture and designers have tried to incorporate the harmonies and patterns of nature into architectural form. Alberti, Charles Renee Macintosh, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Courbusier are just a few of the well- known figures who have taken this approach and written on this theme. With the development of fractal geometry--the study of intricate and interesting self- similar mathematical patterns--in the last part of the twentieth century, the quest to replicate nature’s creative code took a stunning new turn. Using computers, it is now possible to model and create the organic, self-similar forms of nature in a way never previously realized.

In Fractal Architecture, architect James Harris presents a definitive, lavishly illustrated guide that explains both the “how” and “why” of incorporating fractal geometry into architectural design.

In Fractal Architecture, architect James Harris presents a definitive, lavishly illustrated guide that explains both the “how” and “why” of incorporating fractal geometry into architectural design.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fractal Architecture by James Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Man, Nature, and Architecture

CHAPTER 1 The Journey from Mathematical Monsters to the Key to Nature’s Structure

Fractal architecture is an innovative direction in the design and development of architectural form, rooted in the principles that govern the geometry of natural form. Fractal geometry is a recursive mathematical derivation of form that possesses a self-similar structure at various levels of scale or detail and, if the number of recursions is large, results in a dense structure that challenges dimensional qualification. An understanding of the genesis, attributes, and principles of fractal geometry provides a foundation for comprehending the structure of natural forms. What began as a study of geometric “monsters” transformed over time into a fascinating key to understanding the structure of nature. The analysis of the characteristics of this structure serves as a springboard for applying these principles to architecture.

HISTORY OF FRACTAL GEOMETRY

Fractal geometry is part of a nonlinear revolution that has prompted the reevaluation of the nature of mathematics and science as well as reformulating philosophical thought. The predecessors of fractal geometry were based in a linear geometry developed by a Greek mathematician, Euclid of Alexandria. Euclid authored Elements, a textbook outlining a set of logical principles deduced from a small set of axioms to form what is known as Euclidean geometry. These principles describe a methodology of constructing geometric objects, including three-dimensional primitives, which were espoused by Plato as the building blocks of the universe. From 300 b.c. up through the nineteenth century, these rules dominated mathematical thought. During the early 1600s, the French philosopher Descartes built on these tenets and introduced the concept that our universe could be quantified by the Cartesian coordinate system, in which three poles intersect perpendicularly, typically labeled as the x, y, and z axes. These are articulated with perfectly even gradations, providing the ability to locate everything precisely in space.1 These clear and geometrically rigid axioms were embraced as they provided clarity in modeling system behavior and lifted it from the randomness of the universe, which was beyond understanding. The randomness within the human environment was seen as Nature’s screen, used by her to hide her pure forms. These early philosophers could not conceive that calm equilibrium and turbulent chaos could be one within Nature’s body and inseparably interlaced in the pure abstract harmony of a single mathematical equation.2

Figure 1.1. a. Cantor’s Dust; b. Peano’s Curve.

Nature, however, appears to have been playing a joke on mathematicians, asserts Benoit Mandelbrot, who is considered the father of modern fractal theory. Mathematicians may have been lacking in imagination, but Nature was not.3 Beginning in the nineteenth century, a revolution in mathematical thought commenced, propelled by the discovery of mathematical structure that did not fit the precepts of Euclid, Descartes, or Newton. Mathematicians such as George Cantor, Giuseppe Peano, David Hilbert, Gaston Julia, Helge von Koch, Waclaw Sierpinski, Gaston Julia, and others created abstract forms that held clues to understanding nature in a visual sense4 and provided glimpses into infinity. Although all these structures served as models for the complexity of nature, they were regarded with distaste as geometric aberrations, a pathological “gallery of monsters.” These constructions, however, brought into question some of math’s fundamental beliefs. During this period of crisis, these pioneers came in contact with bizarre shapes that challenged the prevailing concepts of time, space, and dimension.5

Cantor’s Dust was formulated by George Cantor by taking a line segment, a one-dimensional object, and replacing it with two copies one third the length of the original placed at either end of the original line. The resulting figure appeared to be the original line with the middle third missing. The process was repeated on each of the remaining line segments, splitting each one into thirds and deleting the middle third. As you continue the process to infinity, it appears that you jump in dimension from the one-dimensional line to a series of zero-dimensional points or dust: Cantor’s Dust (see Figure 1.1a).

A similar but diametrically opposite construct was developed by Italian mathematician Guiseppe Peano when, in 1890, he invented the Peano Curve (Figure 1.1b). In this geometric object, a jump from one dimension to the second dimension is achieved in that a continuous curve of one dimension with no width or area could fill a region of space. Each time you repeat the process of substitution, you leave less space between the lines, and if you carry the process to infinity, theoretically, you fill the space. Cantor’s Dust transformed a one-dimensional object into zero dimensions, whereas Peano’s curve took a one-dimensional object and visually made a two-dimensional figure.

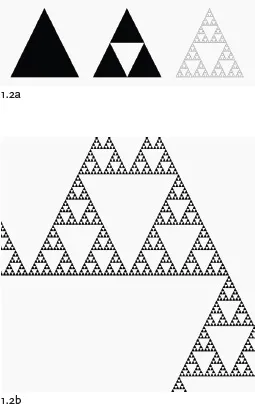

Figure 1.2. a. Sierpinski’s Gasket; b. Sierpinski’s Gasket detail.

Waclaw Sierpinski developed one of the most recognizable fractal forms: the Sierpinski Gasket (Figure 1.2). The base object is a solid triangle that is replaced by three copies of the triangle scaled down to one-third of its original size. Each of the three copies is translated to one of the points of the triangle. The resulting figure is essentially the original triangle with an unfilled upside-down triangular hole in the middle. It is in fact a set of three scaled-down copies. The process is repeated again, resulting in each of the three solid triangles being replaced with a triangle with a hole, which is really a set of three copies of the previous object. The process is repeated as many times as you want, replacing each solid triangle with a scaled-down copy of the set of three solid triangles separated by an upside-down triangular hole (Figure 1.2). This process is theoretically continued to perpetuity. The fascinating part is that if you start to zoom in on a section of the Sierpinski Gasket, a structure will be revealed that appears very similar to the overall object: a triangulated gasket. Each time you zoom in on a section of a previously zoomed-in section, you will see the same similar triangulated structure—a visual glimpse into infinity.

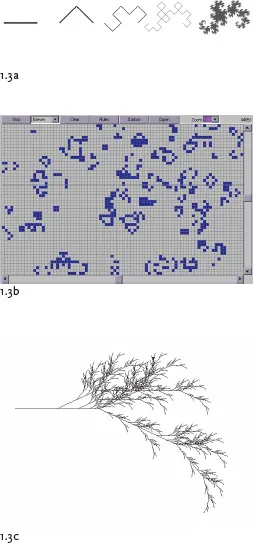

After the burst of innovative mathematical inquiry in the years around the turn of the nineteenth century, research plateaued because of the arduous calculations involved in the generation of these new geometric shapes. Mathematicians spent days and weeks drawing by hand their experiments with the new visual universe. These initial drawings tended to be crude and inaccurate. The burden of hand calculations and graphic representation stymied research until the advent of computers.6 With the introduction of computers, what took days and weeks could be done within seconds with pinpoint accuracy. The mathematical revolution picked up where it left off in the middle to late twentieth century. John Heighway continued research into iterative construction with Heighway’s Dragon (1960) (Figure 1.3a). Stanislaw Ulan and John von Neuman’s 1940s research into crystal growth and self-replicating systems was developed by John Conway and Marin Gardener into the Game of Life, which was based on their theory of cellular automation (Figure 1.3b). Aristid Lindenmayer developed a formal language utilized to model plant growth called L-Systems (1968) (Figure 1.3c).

Figure 1.3. a. Heighway’s Dragon; b. Conway’s Game of Life; c. L-System.

The primary figure in this mathematical revolution was Benoit Mandelbrot, who brought fractal theory to the forefront of scientific consideration. Mandelbrot acknowledges the work of his predecessors: “I rejoiced in finding that the stones I needed—as architect and builder of the theory of fractals—included many that have been considered by others.”7 In the late 1950s, Benoit Mandelbrot was a staff mathematician at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center. His assigned task was research methodologies to eliminate noise that disrupted signal transmission. In his investigation he recognized a complex configuration of chaos and concluded that the technology that IBM was developing would not be able to contain it. Although he had no training in telecommunications, the structure of the noise was similar to the research Mandelbrot had done with cotton prices. Starting in the early 1950s, he researched commodities prices and concentrated on cotton prices because of the availability of pricing data from centuries of trading. During that time, the price of cotton behaved with a degree of consistency. The amount the price varied over centuries was similar to the amount it varied over decades, which was similar to the amount it varied over years. If magnified, the price of cotton during any particular duration of time held a similar pattern to that of the entire period of study. Mandelbrot termed this statistical equivalence scale invariance. In examining these curves, you see cycles within cycles within cycles; however, the embedding of each cycle is not simple. Each cycle has a certain amount of variation, and although the range of variation is consistent, the variation of a cycle within the variation makes predictability at every point in time and at every level of scale difficult.8

Other phenomena, such as river discharges, coastlines, and commodity and stock market prices, exhibit the same acutely cyclic structure. Mandelbrot developed a series of forgeries of the graphs of these chaotic phenomena. These phenomena fluctuate up and down in cycles in that they contain cycles within cycles within cycles. They are perfected by adding a random factor at each step that makes them aperiodic and more genuine. These charts were shown to experienced practitioners of the various fields, who could not tell whether or not they were real (Figure 1.4).

Fi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I. Man, Nature, and Architecture

- Part II. Nature and Human Cognition

- Part III. Architecture from Nature

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index