eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

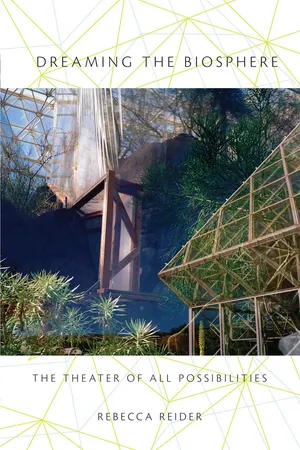

Dreaming the Biosphere

The Theater of All Possibilities

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

"Biosphere 2" rises from southern Arizonas high desert like a bizarre hybrid spaceship and greenhouse. Packed with more than 3,800 carefully selected plant, animal, and insect species, this mega-terrarium is one of the world's most biodiverse, lush, and artificial wildernesses. Only recently transformed from an abandoned ghost dome to a University of Arizona research center, the site was the setting of a grand drama about humans and ecology at the end of the twentieth century.

The seeds of Biosphere 2 sprouted in the 1970s at Synergia, a desert ranch in New Mexico where John Allen and a handful of dreamers united to create a self-reliant utopia centered on ecological work, study, and their traveling experimental theater troupe, "The Theater of All Possibilities." At a time of growing tensions in the American environmental consciousness, the Synergians took on varied projects around the world that sought to mend the rift between humans and nature. In 1984, they bought a piece of desert to build Biosphere 2. Eco-enthusiasts competed to become the eight "biospherians" who would lock themselves inside the giant greenhouse world for two years to live in harmony with their wilderness, grow their own food, and recycle all their air, water, and wastes.

Thin and short on oxygen, the biospherians stoically completed their survival mission, but the communal spirit surrounding Biosphere 2 eventually dissolved into conflict--ultimately the facility would be seized by armed U.S. Marshals. Yet for all the story's strangeness, perhaps strangest of all was how normal Biosphere 2 actually was. The story of this grand eco-utopian adventure (and misadventure) becomes a parable about the relationship between humans and nature in postmodern America.

Visit the authors' website at www.dreamingthebiosphere.com

The seeds of Biosphere 2 sprouted in the 1970s at Synergia, a desert ranch in New Mexico where John Allen and a handful of dreamers united to create a self-reliant utopia centered on ecological work, study, and their traveling experimental theater troupe, "The Theater of All Possibilities." At a time of growing tensions in the American environmental consciousness, the Synergians took on varied projects around the world that sought to mend the rift between humans and nature. In 1984, they bought a piece of desert to build Biosphere 2. Eco-enthusiasts competed to become the eight "biospherians" who would lock themselves inside the giant greenhouse world for two years to live in harmony with their wilderness, grow their own food, and recycle all their air, water, and wastes.

Thin and short on oxygen, the biospherians stoically completed their survival mission, but the communal spirit surrounding Biosphere 2 eventually dissolved into conflict--ultimately the facility would be seized by armed U.S. Marshals. Yet for all the story's strangeness, perhaps strangest of all was how normal Biosphere 2 actually was. The story of this grand eco-utopian adventure (and misadventure) becomes a parable about the relationship between humans and nature in postmodern America.

Visit the authors' website at www.dreamingthebiosphere.com

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dreaming the Biosphere by Rebecca Reider in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

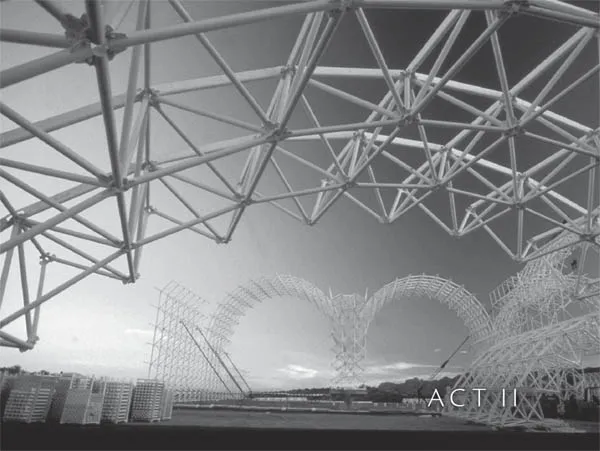

The “space frame” rises into

the air over the future

biospherian farm area.

© PETER MENZEL /

WWW.MENZELPHOTO.COM.

the air over the future

biospherian farm area.

© PETER MENZEL /

WWW.MENZELPHOTO.COM.

GENESIS

And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed.

And out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. . . .

And the Lord God took the man, and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and keep it.

—Genesis 2:8–15

These are the generations of Noah: Noah was a just man and perfect in his generations, and Noah walked with God.

And God said unto Noah, the end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them; and behold, I will destroy them with the earth.

Make thee an ark of gopher wood. . . .

And of every living thing of all flesh, two of every sort shalt thou bring into the ark, to keep them alive with thee. . . .

—Genesis 6:9–19

EVERY WORLD HAS ITS CREATION STORY. IN 1982, AT THE INSTITUTE OF Ecotechnics Galactic Conference in southern France, Phil Hawes stood at the blackboard and held up a white sphere, not much larger than a basketball, for the guests to see. The gathering that year included assembled friends from synergias around the world, and the invited speaker-guests included a few world-famous icons of alternative thinking, among them Buckminster Fuller and microbiologist Lynn Margulis, champion of the Gaia Hypothesis. Now Hawes—who himself had bounced around the planet designing ecotechnic projects—stood before them all. From behind glasses and a long brown mustache, he explained his latest tiny creation, which he had made at John Allen’s urging. It was a model of a spherical adobe enclosure to be built at a size of 110 feet in diameter. The group was by this time used to wild ideas, but the leap from the adobe houses that Hawes and his team had once built in New Mexico was ambitious even by their standards—for this sphere was designed for life in space. The spaceship would rotate in order to produce its own gravity, Hawes explained to the audience. Furthermore, it would be not just a vehicle, but a place to live, a self-sustaining world. Apartments, gardens, and wilderness areas would line the sphere’s curving inner edges. Human inhabitants would cultivate plants and animals, including miniature cattle bred for space travel. Biodiversity would come from a store of cryogenically frozen genetic material for the propagation of twenty thousand different species. At the sphere’s center would be a zero-gravity “Globe Theater” where actors and audience could float—in three dimensions, a true theater in the round. The plans were purposefully fanciful, a play of ideas, and no one, Hawes included, walked away with intentions of actually building such a structure. But it served another purpose: it got the conference delegates talking.

It was two years later, in the autumn of 1984, when Tony Burgess received a phone call at his home in Tucson that he would never forget. Tony was a red-bearded dryland botanist who had designed the desert garden on top of the Caravan of Dreams performing arts complex in Fort Worth. Now, two years after that project, Margret Augustine was on the telephone, and she wanted to know if she, John Allen, Ed Bass, and others could come meet at Tony’s house at ten o’clock that Friday night. When they arrived and sat down, John Allen made an announcement: “We’re going into the space race.”

Two days later, the small group drove out of town along the base of the mountains, into the cactus-dotted hills near Oracle, to inspect the land they were already considering for their new project. John Allen had picked southern Arizona as the prime site for a world under glass, as year-round sunlight would keep plants growing in every season. Now Allen wanted Tony and his friend and fellow ecologist Peter Warshall to make sure the proposed site had no major ecological problems—but, as Tony recalled, the deal was sealed when their party came over the crest of the hill and looked out at the breathtaking desert view. The setting was spectacular, under the foot of the sharp Santa Catalina Mountains. Here they could buy 1,800 acres of high-elevation desert. It was an open space of dried-up washes and low ridges, peppered with woody mesquite undergrowth, dry grasses, and cacti, and roamed by lizards and herds of wild peccaries. Only an hour’s drive north of Tucson, the site sat within reach of two major airports, making it accessible to guests, yet far enough out in the desert to keep some privacy. The nearest neighbors lived several miles up the highway in Oracle, an isolated little town of working-class families and artists.

The site for the new world possessed only a little cluster of living spaces and meeting rooms that the Motorola Corporation, and later the University of Arizona, had been using as a conference center. The founders named their new land SunSpace Ranch. And only a few months later, in December 1984, the ranch opened for its first gathering: the Biospheres Conference.

Institute of Ecotechnics members again jetted in from their outposts around the world, with representatives present from the projects in Australia, Puerto Rico, Kathmandu, Santa Fe, London, Fort Worth, and at sea. The conference program listed the Ecotechnics members as “Research Associates” and John Allen as their “Total Systems Consultant”—their new professional roles in a theatrical science production. As always, the other invited guests were an eclectic and fascinating collection: space engineers, NASA astronauts, and visiting scientists in fields ranging from human medicine to chaos mathematics to microbiology. But this time they were not simply gathered for collegial intellectual exchange. They had been summoned to offer advice on a project that would need the expertise of everyone in the room. After dinner John Allen rose, and the lively chatter of the guests quickly fell silent. He greeted the gathering: “Friends and fellow students of the universe!” And he confidently told them their mission: to create “the first mitosis of Biosphere Planet Ocean”—the first offspring of their home planet, a new world. If this first experiment of Biosphere 2 worked, Allen proclaimed, new biospheres could one day support permanent settlements on other planets. With their help, Earthly life and intelligence could spread throughout the universe. They would start on this site in the Arizona desert, but their target would be, he concluded in patently grand language, “the objective history of man on this planet, which is the struggle to realize all possibilities.”

The visiting scientists sat gaping as Allen announced that he intended to go to space for artistic reasons, not military reasons. “We were all stunned at that point,” Tony Burgess recalled. “There was a lot of giggling. We couldn’t believe this was happening.” But, he said, “It was neat to see that they were going to use some interesting science to do something way out of the ordinary.” After only a few days of talking, many of the scientists were hooked. After all, they were being offered the chance to play with millions of dollars, in order to recreate their favorite ecosystems of expertise under glass.

As they built excitement around their new project, the Institute of Ecotechnics crew already talked as if they were embarking on an expedition to a foreign land. When Mark Nelson, the chairman of the Institute and Allen’s longtime collaborator, stepped to the microphone at the Biospheres Conference, his rhetoric rang less of biology than of manifest destiny, as he declared in a measured, slow, but strong voice,

Perhaps childhood’s end is at last at hand. Alexander the Great reportedly wept that there weren’t other worlds to conquer. What would he say to the prospect of creating new worlds, and sending them into Cosmos? We stand as travelers at the crossroads, armed with technics so powerful as to both threaten the continuation of our species, and perhaps our very biosphere—but technics which also make possible the accomplishment of man’s oldest dream . . . As children of Gaia, the Earth’s present biosphere, we have the opportunity, unique in our history, and perhaps a necessity, to pay back the debt for our upraising, to initiate a new science and practice of biospherics.

His words were dramatic but fit the occasion. Later Nelson reflected, “Many of the people who were involved at NASA during the Apollo project of the sixties compared the spirit they found at Biosphere 2 with the excitement at NASA during those years—when everyone knew what was being attempted was damn near impossible but a hell of a challenge.”

Some in the conference room already believed they could be heading for outer space within a few decades. (As a reporter later observed, “Here people talk very casually about retiring on Mars. Here people talk about Mars as if it were France.”1) The last section of Mark Nelson and John Allen’s little black book, Space Biospheres, first published in 1986 by the project’s own Synergetic Press, would include sketches for a “Mars Science Station and Hospitality Base” made of four interlocking biospheres. The authors were already considering the mountains and canyons of the red planet for the most scenic place to build their next home. Their portrait photographs in the back of the book showed them stony-faced, wearing coats and ties, gazing intently toward the horizon as though toward the stars.

From the beginning, to its creators Biosphere 2 was much more than an ecological project, more than a glass greenhouse, and even more than a model space station. The structure’s name evoked cosmic-size purposes; it was to be, quite literally, a new world. In the early 1980s, the term biosphere was scarcely in use, even among scientists. “Initially the name of the Biosphere company was Space Biospheres Ventures,” recalled Kathy Dyhr, the project’s publicity director, but “we just put it on our checks as ‘SBV’ because if you said ‘biosphere’ to anybody, even scientists would say, ‘What the hell is that?’ ” The obscure term dated back to 1875, when an Austrian geologist named Edward Suess coined the word biosphere to refer to the envelope of life forms covering the Earth’s surface. Then, in the early twentieth century, a Russian geochemist, Vladimir Vernadsky, had more fully elaborated the concept. Vernadsky explained in his 1926 monograph The Biosphere how all living organisms, functioning as a whole, together shaped conditions on Planet Earth. To Vernadsky, the term biosphere signified the totality of living beings, together with the air, minerals, and water that they controlled through biogeochemical cycles. Still, the Russian thinker’s work remained little known outside the Iron Curtain. It would not even be published in English until Biosphere 2’s builders put out a book of excerpts in 1986.

What would it mean, then, to create a Biosphere Two? The cocreators’ logic was grand but poetically simple from the beginning. Every day, the Earth’s countless life forms were busy maintaining the chemical and ecological balance of their world, promoting conditions hospitable to life. It was only a matter of scientific tinkering, then, the Biosphere-builders reasoned, to make a second biosphere—to put together a combination of plants, animals, air, soil, water, and energy so that the constituent parts could evolve into their own self-perpetuating system. The Earth itself would no longer be the only known biosphere in the universe; it was, in the project’s lingo, merely “Biosphere 1.” The assembled scientists and builders of Biosphere 2 would be midwives to the birth of a new world.

Biospheres 1 and 2 would differ in obvious ways: Biosphere 2 would take up a giant glass greenhouse, not a whole planet; and Biosphere 2, unlike the Earth, would need a massive power plant to keep its air blowing, water flowing, and temperature stable. Yet Biosphere 2 would become like a whole world to its participants. In their manifesto Space Biospheres, John Allen and Mark Nelson set out their own working definition of a biosphere. They argued that a biosphere was a “stable, complex, adaptive, evolving life system,” containing the five kingdoms of life and including multiple “biomes,” such as the rainforest, ocean, and desert.2 According to Allen and Nelson’s logic, just as Biosphere 1 was open to inputs of energy from the sun, likewise Biosphere 2 should also be allowed to receive inputs of outside energy—even if those inputs came not only from the sun but also from a man-made power plant. Thus, with a few slippages and convenient analogies, the idea of Biosphere 2 came into being.

Though Biosphere 2 was barely a sketch on paper, in its creators’ minds it was already the subject of many different dramas. The project leaders spoke of space, cosmic destiny. Meanwhile, the invited scientific consultants were excitedly talking among themselves about a different question: Did science have the ecological knowledge to actually build a new world? Many of the designers had experience in constructing ecosystems, but on smaller scales. Tony Burgess, a U.S. Geological Survey biologist, had previously put together the Desert Dome rooftop garden for the Caravan of Dreams arts center. Ghillean Prance, the Amazon expert who would plan out Biosphere 2’s rainforest, had worked for years at the New York Botanical Garden, in its vast greenhouses enclosing exotic species. Walter Adey, the marine systems designer, was in the midst of building a miniature version of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem in tanks in the basement of the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. But none of them had ever had to design a whole world that could survive on its own.

Carl Hodges of the University of Arizona’s Environmental Research Laboratory would, along with his colleagues from U of A, oversee the development of Biosphere 2’s agriculture systems and ecotechnologies. Hodges was an unconventional thinker and a doer, a well-known specialist in coaxing agricultural production out of harsh environments and in designing ecotechnological systems. And so, at that first Biospheres Conference in 1984, when he got up to make his keynote speech on the “The Do-ability of a New Biosphere,” everyone was listening. Hodges proudly described his own lab’s long track record of successful experiments: they had figured out how to grow crops with desalted seawater in the Middle East, how to farm shrimp in controlled enclosures in Mexico, and even how to use untreated seawater for irrigation of salt-loving plants. The key to “making the desert bloom,” Hodges argued, was to learn from nature and base engineering designs on natural systems. If people designed a system smartly, they could survive on only about half an acre of land apiece, he estimated. Finally, with firm conviction, he made his pronouncement on the scientific prospect of creating an entire enclosed world: “It’s totally doable.”

The scientists eagerly discussed ideas for the huge new experiment. “We were going to use this as a focal point for all these disciplines,” Tony Burgess told me years later, sitting back at his kitchen table in Tucson, his face lighting up as he recalled the initial excitement among his colleagues. “What we thought we were going to do . . . was that once we fused those disciplines, emerging from that project would be a whole new perspective on looking at and managing the ecosystems of the Earth.” Tony himself felt that by setting up Biosphere 2’s desert, he could repay his debt to scientists who had set up ecological observation plots in the Arizona desert eighty years earlier. Those plots had yielded research results that helped generations of scientists, including himself. “With this much focus on a small system, as [Biosphere 2 savanna designer] Peter Warshall pointed out, we were going to invent, and really refine, what he called ‘invisible ecology,’ ” Tony recalled. “The ecology we naturalists had been trained in was the ecology of fuzzy things and trees and tangibles that you could see; this invisible ecology was going to be the flux of molecules, atoms, compounds, energy.” The chance to just play with plants also appealed to the scientists. As a scientist working on his own PhD in the Arizona desert, Tony said, “I missed the creativity that one could do with more artistic things, and this project allowed me to see myself doing creative designs and construction . . . It was a very liberating experience.” The grand experiment quickly became not just a consulting job but a passion for many of the hired scientists, he said. “It had to be a passion to get it done.”

While the scientists dreamt of ecological possibilities, the Theater of All Possibilities members were imagining different plot lines. In their minds some were already headed for Mars. The script was already written in their plays. In 1983, the year before Biosphere 2 became a plan, the troupe had performed an original drama called Kabuki Blues. The play told the story of a supposedly fictitious guru figure named “Mr. Kabuki”—though his personality was coincidentally similar to the play’s author Johnny Dolphin (John Allen)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dramatis Personae

- Prologue

- Act I

- Act II

- Act III

- Act IV

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Photographs follow page