eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821

About this book

Kelly Donahue-Wallace surveys the art and architecture created in the Spanish Viceroyalties of New Spain, Peru, New Granada, and La Plata from the time of the conquest to the independence era. Emphasizing the viceregal capitals and their social, economic, religious, and political contexts, the author offers a chronological review of the major objects and monuments of the colonial era.

In order to present fundamental differences between the early and later colonial periods, works are offered chronologically and separated by medium - painting, urban planning, religious architecture, and secular art - so the aspects of production, purpose, and response associated with each work are given full attention. Primary documents, including wills, diaries, and guild records are placed throughout the text to provide a deeper appreciation of the contexts in which the objects were made.

In order to present fundamental differences between the early and later colonial periods, works are offered chronologically and separated by medium - painting, urban planning, religious architecture, and secular art - so the aspects of production, purpose, and response associated with each work are given full attention. Primary documents, including wills, diaries, and guild records are placed throughout the text to provide a deeper appreciation of the contexts in which the objects were made.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821 by Kelly Donahue-Wallace in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Graphic Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Architecture and Sculpture at the Missions

While today it is easy to reduce the colonization of New Spain and Peru to the events surrounding Hernán Cortés’s battle for Tenochtitlan or Francisco Pizarro’s defeat of the Inca at Cajamarca and Cuzco, the imposition of Spanish authority in the American colonies was neither sudden, spectacular, nor definitive. Colonization was instead a long process during which the new social and political order was introduced time and again to each individual community. Relatively few indigenous people, in fact, had direct contact with the battles chronicled in history books. For most Amerindians in the soon-to-be-designated viceroyalties, mendicant friars and the missions they constructed constituted their first sustained exposure to colonization. In manners as diverse as the peoples themselves, indigenous Americans interacted with the new religious representatives at the missions; some rejected the friars’ presence while others folded Christianity and its human authorities into their spiritual lives. All negotiated their position within the new system and reconciled the foreign faith with the local.

Most of the earliest examples of Spanish colonial art and architecture came from the missions. The mendicant friars working in New Spain and Peru constructed missions to convert native peoples to Christianity. Many of these conventos remain today as the physical—and sometimes still active—remains of the evangelical era. During this period, which lasted from 1524 to circa 1580 in New Spain and 1532 to 1610 in Peru, the Franciscan, Dominican, Augustinian, Mercedarian, and, later, Jesuit monastic orders devoted themselves to persuading indigenous Americans to abandon pagan religions for Christianity. The Spanish Crown was likewise committed to the effort. From our vantage point centuries later, we can see that the success of this evangelical program varied widely, from communities that embraced Christianity to those that accepted little of the new teachings. At the time, of course, both church and crown declared its unequivocal success.

The spread of Christianity in the Americas suited the needs of both the Spanish crown and the mendicant orders. The Spanish monarchs Charles I (r. 1516–56) and his son Philip II (r. 1556–98) had both spiritual and earthly motives for converting native peoples. At their core was the firmly-held belief that Christianity was the only true faith; all other religions, therefore, were misguided and those who followed them put their souls at risk. By the early sixteenth century, Spain had experience in extirpating false religions from its territory, including the 1492 defeat of the last Moorish caliphate in Granada and the expulsion from the Iberian peninsula of all Jews and Muslims who refused to abandon their faiths. The kings furthermore interpreted their victory in Granada as proof of God’s approval of Spain’s spiritual cleansing. Upon discovering the peoples of Meso- and South America, the monarchs considered the conversion of Amerindians to Christianity to be God’s will.

Spain’s evangelical program functioned with the support of the Roman Catholic Church, which granted the crown expanded authority to implement the missionary effort. In 1508, Pope Julius II authored the bull Universalis Ecclesiae, giving the Spanish kings religious authority over the territories they received in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas.1 This Patronato Real, as it was known, included the right to appoint bishops and archbishops, to collect tithes, to implement religious building programs, and generally to direct the spiritual life of the viceroyalties. In return for this unprecedented authority, the Spanish monarchs pledged to convert the native populations to Christianity, which they did by establishing missions in indigenous communities.

Converting indigenous peoples also had more earthly benefits for the crown. Aside from creating a population of Spanish citizens that made the empire the largest in the world—certainly bigger than Spain’s rivals France and England— religious conversion represented a means to control territory. The Spaniards did not have the large standing armies needed to dominate by military force. They did have a spiritual militia of ready and willing clergy who forged into unconquered lands to transform pagan Amerindians into Christianized Spanish subjects. Spanish monarchs assumed that once converted, these Amerindians were less likely to rebel against colonial authority than un-Christianized natives. Hence the missions represented an inexpensive and efficient alternative to deploying soldiers across two vast continents.

The mendicant orders of the regular branch of the Roman Catholic Church, for their part, shared the crown’s belief in the inherent fallacy of pagan religions and in the moral superiority of Christianity. The Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian friars furthermore believed that Christ’s second coming, an event seen as impending since the turn of the millennium, was only possible when all people on earth were introduced to his teachings. This millenarianism drove the clerics to pursue urgent Christianizing efforts in the Americas so that the biblical prophecy might be realized. The mendicants furthermore saw these lands as an opportunity to construct anew a Christian society untainted by the corruptions plaguing the European church during the sixteenth century. They looked at the indigenous peoples as tabulae rasae, blank slates upon which to inscribe a pure form of the faith based on the values of early Christianity. The missionaries likened themselves to the apostles charged by Christ to spread his teachings, and set out to create Christian repúblicas de indios, communities of Amerindians.

The mendicant clergy were not always of the same mind as the crown, however, especially when it came to the Spaniards’ mistreatment of natives. While the friars understood much of traditional Amerindian life as wrong and occasionally even demonic, they nevertheless defended Spanish America’s indigenous peoples against abuses. Much of the problem lay in the encomienda system by which the Spanish Crown granted conquistadors and colonists the right to native tribute and labor within discrete regions; in return, the encomenderos agreed to provide religious instruction. This system placed Spaniards at the head of traditional tribute systems with little effective oversight by civil authorities. The encomienda system consequently was rife with abuses and the mendicant clergy regularly decried the abysmal working conditions and mistreatment of their native charges. At the root of the problem was the colonizers’ perception of Amerindians as inherently inferior, even subhuman, beings. The 1542 New Laws of the Indies imposed new protections for native peoples and sought to phase out the encomienda system in favor of crown-administered drafts. Neither system pleased the clerics, although they, too, relied on labor corvées to construct their conventos.

The missionaries arrived in New Spain and Peru in ever greater numbers throughout the sixteenth century. The first friars to reach Mesoamerican shores were three Franciscans who began work in Mexico City in 1523; twelve more arrived in New Spain’s viceregal capital the following year. The same number of Dominicans reached the city in 1526, followed seven years later by a group of Augustinian friars. In South America, the Dominican, Franciscan, and Mercedarian orders reached the Inca capital of Cuzco in 1534 and Lima, Peru’s viceregal capital, in 1535; the Augustinians arrived in Lima in 1551. The newly founded Jesuit order was a late arrival in both viceroyalties, reaching Peru in 1568 and New Spain in 1571; their well-trained clergy and military-style order nevertheless made them indispensable despite their tardy entrance.

Upon arriving in Mexico City, Lima, Cuzco, Quito, and other larger colonial settlements, all of the orders constructed grand convents. Many of these would serve as the orders’ principal monasteries and administrative centers—or mother houses—for the next three centuries. Most of the early urban foundations appear today in forms altered by construction programs that continued throughout the colonial era. The Convent of Santo Domingo in Cuzco, however, retains some of its early appearance, although most of the compound was reconstructed after the 1650 earthquake. In particular, the church’s apse end (Figure 1) rests on the dressed masonry foundations of the Inca Coricancha, a temple dedicated to the sun and described by early observers as sheathed in gold. The Dominicans in Cuzco, like their colleagues elsewhere in Latin America, built upon this sacred site as a symbol of the new religious and social order. This strategy of physical appropriation and imposition had its roots in early Christian European practice and persisted throughout the colonial era. Although the Amerindian viewers undoubtedly understood the spirit of these acts, viewing remains of pagan temple foundations, pyramid platforms, and even sculpture incorporated into Christian churches may have evoked memories and religious sentiments distinct from what the friars tried to teach.

While the mother houses ministered to the indigenous populations and Spanish colonists living in the newly founded—or at least newly Hispanized— cities, they also sheltered the missionaries on their way to outlying Amerindian communities. Traveling in pairs, sometimes on foot and other times on donkeys, the missionaries founded cabeceras or main monasteries in larger towns. These were occupied by a handful of permanent clergy (or even just one), whereas the visita churches founded in smaller villages were visited on a regular schedule but not inhabited by resident friars. As the clerics entered the indigenous towns, they forged relationships with local leaders or caciques, whose assistance was essential in converting the population. Some of the villages were reducciones, newly created or coalesced native towns constructed to facilitate conversion, with the missions at their physical and spiritual center. Missionaries similarly claimed the core of existing villages, sometimes building on the ruins of temple platforms or pyramids as mentioned. As this process replayed throughout the sixteenth century, the mendicants constructed over four hundred missions across the New Spanish and Peruvian landscapes.

With their missions founded, at least symbolically while building got underway, the missionaries set to work teaching Amerindians about Christianity. Their methods for doing so, however, varied widely, and the experimental strategies the missionaries employed, including preaching in the native languages, were debated from the outset. The regular orders, like the Spanish crown, had unprecedented freedom in their conversion efforts. The papal bulls Alias Felicis (1521) and Exponi Nobis Fecisti, also known as the Omnimoda (1522), gave the mendicants authority to perform sacraments, a right usually reserved for the secular clergy; friars baptized native peoples, performed masses, officiated marriages, and heard confessions. This expanded authority did not sit well with the parish priests, bishops, and archbishops of Latin America’s growing secular clergy. By the end of the sixteenth century, six church councils had been held in Mexico City and Lima to clarify ecclesiastical practices and the relationship of the missionaries to the episcopal hierarchy.

FIGURE 1. Church of Santo Domingo. Reconstructed after 1650. Cuzco, Peru. Photograph © Kelly Donahue-Wallace.

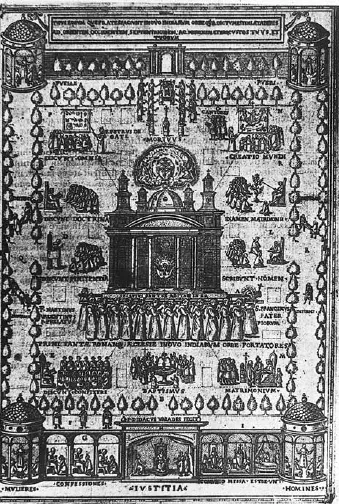

FIGURE 2. Fray Diego de Valadés, Allegorical Atrium from Rhetorica Christiana. 1579. Engraving. photograph © Archivo Fotográfico Manuel Toussaint, IIE/UNAM.

The 1579 engraving known as the Allegorical Atrium (Figure 2), referring to the open square preceding the church and monastery, pictures the missionaries’ activities. The engraving, published in fray Diego de Valadés’s Rhetorica Christiana (Perugia, 1579), emphasizes the mission’s didactic role. No less than nine lessons take place within the atrium’s walls, with friars teaching Christian doctrine, sometimes with the help of visual aids to illustrate abstract concepts for friars still learning native languages. Each lesson is attended by native neophytes identified by the tilmas (robes knotted at the shoulder) worn by the Aztecs of central New Spain. The devastating effect of European diseases on the Amerindians also appears in the print, as friars shelter the sick in the infirmary and perform funerals. In the center, New Spain’s Franciscans, symbolically led by the order’s founder, St. Francis of Assisi, bear on their shoulders the new church they created in the Americas.

Missions in the Viceroyalty of New Spain

Evangelical architecture in the Viceroyalty of New Spain began with the Convent of San Francisco in Mexico City and its chapel for Amerindians, San José de Belén de los Naturales. Built in the convent’s atrium, San José de los Naturales may be considered the birthplace of Christianity in New Spain. Fray Pedro de Gante, a Flemish Franciscan whose 1523 voyage to Mexico City preceded the symbolic arrival of his twelve colleagues in 1524, founded the chapel to serve the capital’s Aztec population. There he and his companions taught basic Christian principles to the masses to prepare them for baptism.

San José de los Naturales was more, however, than a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Note on Translations and Terms

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Architecture and Sculpture at the Missions

- Chapter Two: Painting in Sixteenth-Century New Spain and Peru

- Chapter Three: Colonial Cities

- Chapter Four: Religious Architecture and Altarscreens circa 1600–1700

- Chapter Five: Religious Art 1600–1785

- Chapter Six: Architecture and Altarscreens circa 1700—1800

- Chapter Seven: Secular Painting circa 1600–1800

- Chapter Eight: Art and Architecture at the End of the Colonial Era

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index