- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

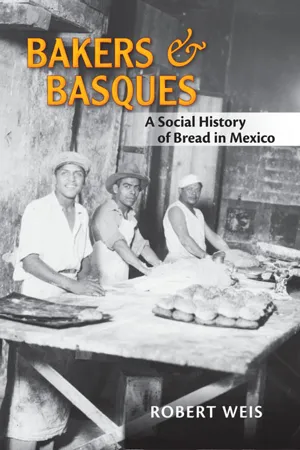

Mexico City’s colorful panaderías (bakeries) have long been vital neighborhood institutions. They were also crucial sites where labor, subsistence, and politics collided. From the 1880s well into the twentieth century, Basque immigrants dominated the bread trade, to the detriment of small Mexican bakers. By taking us inside the panadería, into the heart of bread strikes, and through government halls, Robert Weis reveals why authorities and organized workers supported the so-called Spanish monopoly in ways that countered the promises of law and ideology. He tells the gritty story of how class struggle and the politics of food shaped the state and the market. More than a book about bread, Bakers and Basques places food and labor at the center of the upheavals in Mexican history from independence to the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bakers and Basques by Robert Weis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Mexican History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

“Zelo y desvelo”

The Bread Monopoly and Late Colonial Market Reforms

Bread was part of the Spaniards’ mission to civilize the Native Americans. Friar Bernardino de Sahagún urged the Indians to “eat that which the Castilian people eat” in order to become “the same as them, strong and pure and wise.”2 Bread soon became central to the diet of urban residents, although Mexicans (and many Spaniards) continued to subsist on maize, and wheat was a rarity in the countryside. By the eighteenth century, bread was so important that Alexander von Humboldt, during his tour of Spanish America, estimated that Mexico City consumed as much wheat as many European cities. He assumed that the Spaniards and their Mexican-born descendants consumed the bulk, but this would have been practically impossible. In reality, the majority of the city’s population ate bread either as a base or as a complement.3

Privately owned panaderías made all of the city’s bread. However, since bread fulfilled what consumers and the Spanish Crown considered to be a public function of nurturing residents, it was subject to close supervision by authorities. This supervision was based on the assumption that the Crown and its colonial representatives were the only forces capable of protecting consumers from the intrinsic tendency toward fraud among producers and merchants. Without government restraint, they feared, entrepreneurs would form oligopolies, or business cartels, that could wield disproportionate influence over the everyday life of the city at great cost to both consumers and civil officials. The Crown elaborated a complex series of regulations that aimed to assert royal authority, repress the private sector’s tendency toward abuse, and create a stable, static marketplace that reliably produced bread of predicable quality and weight.4

These laws addressed virtually every detail of the business, and generally, bread was of reasonable quality and price. Yet for all their thoroughness they did not prevent the formation of entrenched elite groups who defrauded the public and the royal treasury. A powerful cartel—organized within an owners’ guild, or gremio—dominated the related wheat, flour, and bread businesses from the early eighteenth century, and probably earlier, until the end of the colonial era. The gremio emerged both despite and because of colonial laws. This chapter explores this contradiction as well as the even more marked contrast that existed between official policy and actual practice. These tensions came to a breaking point during the deep crisis within the Spanish empire in the early nineteenth century. Under the threat of an insurgency, authorities abandoned the model of a static, regulated marketplace in favor of the “absolute liberty” of commerce. They hoped that free-market reforms would encourage competition and bring an abundance of cheap, quality foods to the city. They were partially successful, but the same vicissitudes that sparked the free-market reforms also ended colonial rule.

Markets and Colonial Paternalism

The Crown enacted laws governing the grain and bread trades after a horrific decade of pestilence and hunger, from 1575 to 1585, ravaged much of Mexico and convinced authorities of the need for close supervision of the urban food supply.5 The Fiel Ejecutoría—the Office of the Faithful Executor—was in charge of enforcing these and other regulations related to the production and sale of consumer goods. Bread regulations specified who could purchase how much wheat or flour of what type, from whom, where, and when. They also limited what types of bread bakers could make, and they set prices. Bakers could not sell before seven in the morning, and they had to offer their goods only in certain plazas and streets or in licensed stores. Vending sites were distributed around the city, such that each one would supply a certain neighborhood.6 In theory, since all panaderías provided bread at the same price and complied with the same norms, there was no need for shops to compete with each other. Equilibrium and stability, not competition, was the goal for both the economy and the social order.

For owners or managers, these regulations entailed onerous bureaucracy. Every four months, they had to declare to the Fiel Ejecutoría how much wheat they bought, from whom, when, and at what price. Inspectors corroborated these declarations using those given by the wheat growers. Then, based on the price of wheat, plus bakers’ other expenses such as milling fees, officials set the official weight of bread, known as the postura. The price of bread was permanently fixed at one medio real (one-sixteenth of a peso). What varied over time were the ounces. In good times, a medio real bought eighteen ounces of fine white bread (pan floreado). In slim times, bread could weigh as little as fourteen ounces. The cheaper pambazo (literally “low bread”), made with coarse unsifted flour, usually weighed around forty ounces but could drop to sixteen.7

Officials known as faithful re-weighers (fieles repesadores) regularly checked the weight and quality of bread. To make the inspectors’ job easier, bakeries could only sell at determined spots and had to mark each piece with distinctive registered insignia. Punishment for noncompliance could be severe. Unbranded bread could cost an owner ten pesos for the first offense, four years’ suspension from the trade and two years’ banishment for the second, and “definite suspension, public shame, and perpetual banishment” for the third. Selling underweight bread could land an owner in jail for two years.8

This vigilance sprang from the well-founded assumption that, given the opportunity, panaderías would defraud the public with underweight or poor quality bread. It also provided the colonial state with a platform from which to declare its responsibility to protect subjects from malfeasance and thus reaffirm the paternal relationship between the Crown and its vassals. In declaration after declaration, viceroys, the highest royal authority in the colony, pronounced and celebrated the zelo y desvelo—zealous vigilance—with which they safeguarded the people’s well-being.9

The opposing concept, championed by liberal economists and philosophers of the eighteenth century, posited that an unregulated free market encouraged competition and, in turn, lowered prices and improved the quality of consumer goods.10 The solution to fraud, in this view, was not severe regulation and government control but exactly the contrary, the withdrawal of restrictions on commerce. France and Britain had removed many government controls on food markets, and the free market had influential advocates in Spain, such as the Enlightenment polymath Gaspar de Jovellanos who, like Adam Smith, advocated the removal of regulations that limited the individual’s pursuit of economic self-interest.11 In the Spanish empire movement toward free trade focused on international, and especially transatlantic, commerce and culminated in the broadening of exports and imports in 1778.12 Easing regulations on production and commerce within domestic markets, however, lagged; even Jovellanos recommended continued state regulation of grain prices out of fear of public unrest.

In Mexico colonial authorities similarly distrusted the ability of the free market to produce a positive impact. In their view, they were the only forces capable of protecting consumers from inherently greedy merchants. Without official oversight—the government’s zelo y desvelo—consumers would become victims of all kinds of fraud. If panaderías cheated the public even when inspectors were watching, what would they do without government regulations? Also at stake, of course, were the interests of the influential group of owners who were hardly advocates of opening their business to anyone who happened to have an oven, some flour, and leaven.

The attorney general (procurador general) of the Fiel Ejecutoría clearly articulated this philosophy of a paternal state that oversaw a static, regulated market when in 1779 he rejected the bakery owners’ proposition that the “free market,” the unfettered interplay between diverse buyers and sellers, set prices instead of the government. He responded that if Mexico had not seen the “revolutions over a lack of bread that are so common in the most cultured countries of Europe, where bread production is entirely free,” it was because price fixing had “ensured the public’s peace and tranquility.” Indeed, following the release of bread from strict government oversight in London, Paris, and other cities, bakeries raised prices, and residents rose in revolt.13 Modern ideas and inventions were fine, he said, for “physics, chemistry, shipping, and other sciences.” But to trust the “tranquility of the vassals” to anything beyond the “known rules of economics and prudence” was to court disaster.14

In addition to protecting consumers, colonial regulations aimed to prevent producers and merchants from establishing what the Crown viewed as improper combinations of objects and activities.15 As part of the ideal of static markets, each producer or merchant was to remain within his specific niche. Millers, for example, could not grind wheat of poor quality together with wheat of high quality; likewise, bakers could not mix different flours in their bread. Bakers of sweet breads (bizcocheros) could not make salted bread, under penalty of permanent banishment from the profession. Another law decreed that “bakers cannot be storekeepers and storekeepers cannot be candle makers.”16 The most significant of these regulations prohibited the simultaneous ownership of panaderías and mills. The underlying logic was that businesses gained unfair advantages over other businesses when they mixed things of different natures and bridged distinct trades because these combinations gave them the control of too many economic levers with which they could unduly influence the market, marginalize competitors, and form monopolies. Monopolies could cheat the public by hoarding, speculating, and otherwise manipulating the entire wheat-flour-bread chain. In doing so, they threatened to erode the royal zelo y desvelo, one of the Crown’s key claims to legitimate authority.

If inspectors were generally successful in protecting consumers from the most egregious acts of bakers’ deceit, they completely failed in their goal to prevent improper combinations within the bread trade and, consequently, the formation of a bread cartel. This failure came, in large measure, because all colonial officials in Mexico did not agree with the notion that the interests of monopolies were contradictory to those of inspectors. Many officials, especially those born in Mexico whose charge it was to enforce the laws, saw the bread monopoly as an ally and an asset to their paternalism.17

This tension between law and practice, between Madrid and the streets of Mexico City, came to a head in the mideighteenth century, when the Bourbon monarchs, rulers of the Spanish empire since 1700, set out to centralize authority in the colonies and increase the flow of revenue to the mother country. To this end, they passed more meticulous regulations that aimed to undermine the power of entrenched local elite groups, such as the bread gremio, and to restrict their ability to make illicit profits through abuse and fraud.

The Bread Gremio

Patriarchs of some of the wealthiest families and holders of honorific military and aristocratic titles, panadería owners often served on the city’s governing council and were therefore close to the very authorities in charge of overseeing them.18 They secured their dominance through a gremio, an owners’ guild, whose membership was restricted to a dozen or so major owners who collectively controlled the city’s fifty-odd shops as well as the nearby mills. Such groups of wealthy mill and panadería owners may have dominated the flour and bread trades since the sixteenth century, but the bread trade seems to have been somewhat more open to small producers before the gremio constituted itself as a legal entity in 1742. That year, the Count of Fuenclara became viceroy of New Spain armed with plans to make local government efficient, centralized, and solvent. The dominant owners persuaded Fuenclara that an official gremio strengthened his broader plan to make commerce more reliable and profitable.19 The viceroy ratified the gremio’s bylaws, which allowed members to elect their first legal representative.20

The bakers’ gremio was not a traditional trade guild that brought together skilled artisans. Membership depended on wealth, not skill. Around four thousand pesos were required to contribute to the group’s “administrative and juridical costs.” The bylaws were openly elitist and excluded members of the lower classes—“those whose only possession is the will to be bakers”—because the poor were more inclined to “resort to trickery that would harm the business and the public.”21 According to this self-flattering and deeply deluded vision, the rich had little motivation to defraud the public.

The gremio was an association of owners, most of whom rarely baked or cared to spend much time at all in the workrooms they owned. Most panaderías were sharply divided between owners and administrators, on the one hand, and mostly indigenous workers, on the other. Working conditions in these shops were deplorable, even by colonial ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One “Zelo y desvelo” The Bread Monopoly and Late Colonial Market Reforms

- Chapter Two “A system that offends the hands of brothers” Small Bakers and the Free Market in Independent Mexico

- Chapter Three “An uncle in America” Chain Migration and the Spanish Monopoly

- Chapter Four “Dough Kneaded with Blood”

- Chapter Five “We have no bread” Hunger, Opportunity, and War

- Chapter Six The Bakers’ Revolution

- Chapter Seven Unionists, Tlalchicholes, and Canasteros

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index