This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

A Cherokee Encyclopedia

About this book

A Cherokee Encyclopedia is a quick reference guide for many of the people, places, and things connected to the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokees, as well as for the other officially recognized Cherokee groups, the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of Cherokees.

From A Cherokee Encyclopedia

Crowe, Amanda

Amanda Crowe was born in 1928 in the Qualla Cherokee community in North Carolina. She was drawing and carving at the age of 4 and selling her work at age 8. She received her MFA from the Chicago Arts Institute in 1952 and then studied in Mexico at the Instituto Allende in San Miguel under a John Quincy Adams fellowship. She had been away from home for 12 years when the Cherokee Historical Association invited her back to teach art and woodcarving at the Cherokee High School. . . .

Fields, Richard

Richard Fields was Chief of the Texas Cherokees from 1821 until his death in 1827. Assisted by Bowl and others, he spent much time in Mexico City, first with the Spanish government and later with the government of Mexico, trying to acquire a clear title to their land. They also had to contend with rumors started by white Texans regarding their intended alliances with Comanches, Tawakonis, and other Indian tribes to attack San Antonio. . . .

From A Cherokee Encyclopedia

Crowe, Amanda

Amanda Crowe was born in 1928 in the Qualla Cherokee community in North Carolina. She was drawing and carving at the age of 4 and selling her work at age 8. She received her MFA from the Chicago Arts Institute in 1952 and then studied in Mexico at the Instituto Allende in San Miguel under a John Quincy Adams fellowship. She had been away from home for 12 years when the Cherokee Historical Association invited her back to teach art and woodcarving at the Cherokee High School. . . .

Fields, Richard

Richard Fields was Chief of the Texas Cherokees from 1821 until his death in 1827. Assisted by Bowl and others, he spent much time in Mexico City, first with the Spanish government and later with the government of Mexico, trying to acquire a clear title to their land. They also had to contend with rumors started by white Texans regarding their intended alliances with Comanches, Tawakonis, and other Indian tribes to attack San Antonio. . . .

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Cherokee Encyclopedia by Robert J. Conley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Native American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A.

Abram of Chilhowie

In 1775, following the Cherokee sale of lands to the Transylvania Company, which Dragging Canoe opposed, Dragging Canoe organized raids against what he considered to be illegal squatter communities on Cherokee land. He assigned one of the three raiding parties to Abram of Chilhowie. Abram’s party was to attack the white settlements at Watauga and at the Nolichucky River, running through North Carolina and Tennessee. Abram returned from his raid with a few prisoners, including Mrs. Bean and Samuel Moore, who was burned at the stake. Mrs. Bean was rescued by Nancy Ward, known to history as the “Ghigau,” Beloved Woman. Abram was killed under a flag of truce in 1788 by a Franklin militia led by John Sevier.

Ada-gal’kala

Ada-gal’kala (Attacullaculla, Attakullakulla, the Little Carpenter) was born around 1712 and died in 1778. He was the recognized principal chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1762 until his death in 1778. He first appears in written records in 1730, when Sir Alexander Cuming took seven Cherokees with him to London. One of the seven was Ada-gal’kala, although he was not yet known by that name. As a young man, Ada-gal’kala was called “Okoonaka” (British spelling of the time), which translates as “White Owl.” Englishmen called him “Owen Nakan.” He was likely in his twenties at the time and was described as a small man, slight of frame. He was certainly the youngest of the Cherokees in the group. Ada-gal’kala himself said in later years that he was the first to agree to make the trip. The others only consented afterward.

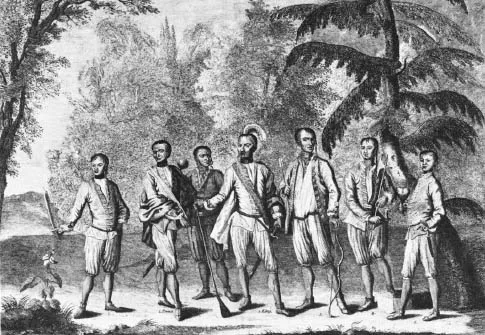

Ada-gal’kala (far right). Engraving by Isaac Basire, London, 1730. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

They left for England on the Fox, a man-of-war, on May 4, 1730, from Charleston, South Carolina, and landed at Dover on June 5. From there they went to London, where they were put up for a time at the Mermaid Tavern and later in an undertaker’s basement in the Covent Garden section. On June 18, they saw the king at Windsor. Following that occasion, they were given new clothes, and in these English outfits they posed for a portrait that may have been painted by either Hogarth or Markham. In the portrait, Ada-gal’kala, on the far right, is holding a gourd rattle in his right hand, with his left hand resting on the haft of a knife hanging from his belt.

The seven Cherokees were taken to see all the sights of London, including a play, the Tower of London, the crown jewels, and a couple of fairs. On September 29, they signed the “Articles of Friendship and Commerce.” Their interpreter, Eleazar Wiggan, gave them a translation of the document after the signing. When they discovered that they had acknowledged the king’s right to the country of Carolina, they talked among themselves and considered killing Wiggan and the Cherokee who had been their spokesman, one “Oukayuda.” At last, however, they decided that because they had no right to cede lands anyway, the agreement could not be binding. They would leave the matter in the hands of the authorities at home. The Cherokees departed for home from Portsmouth on the Fox on October 7. Ada-gal’kala had by this time learned to speak some English.

In 1736, the French sent emissaries to the Cherokees in an attempt to form an alliance. Ada-gal’kala was instrumental in convincing the Cherokees to reject them. Then around 1740, he was captured by the Ottawas, who were allied to the French, and taken to Canada. During his captivity, Ada-gal’kala came to be treated as an Ottawa, for whatever reason, becoming good friends with Pontiac. He also met any number of Frenchmen, including the governor of New France.

When Ada-gal’kala returned to the Cherokee country in 1748, he found the South Carolina traders cheating the Cherokees. “Ammouskossittee” was now the Cherokee “emperor,” and Guhna-gadoga was in effect running things for him. Ada-gal’kala became a trusted advisor of Guhna-gadoga. The South Carolina traders’ behavior and his own eight or so years among the Ottawas had turned Ada-gal’kala toward the French, and he visited with the French-allied Shawnees in Ohio and the Senecas in New York. He returned to the Cherokee country with a rumor that Governor James Glen of South Carolina was trying to entice the Creeks and Catawbas to attack the Cherokees. But the Cherokees attacked South Carolina settlers and settlements instead, and South Carolina imposed a trade embargo.

Many of the Cherokee towns, however, were still strongly in favor of the English, and they agreed to South Carolina’s terms for resuming trade. One of those terms was that “the Little Carpenter” be delivered up to them for having incited all the trouble. Ada-gal’kala and some of his allies went to Virginia, where they attempted to establish trade with that colony because South Carolina was not fulfilling its obligation. Virginia was hesitant to start trouble with South Carolina, but South Carolina’s attitude did soften somewhat. When Lower Town Cherokees visited Charleston, Governor Glen asked only that they “oblige” Ada-gal’kala to make a trip to Charleston to explain his behavior. It is instructive to note the absence of an “emperor” from all these shenanigans and the nonexistence of any real concept of “nation” in the Cherokee towns’ behavior.

By this time, Ada-gal’kala was already known by his new name. We do not know when that came about or why. “Ada-gal’kala” can be translated as “Leaning Wood,” and the British had come to call the man “the Little Carpenter,” presumably playing on his name and the fact that he was known to be able to “craft a bargain [skillfully].” His reputation was already firmly established.

Ada-gal’kala may have been pro-French, but he probably also discovered that the French were unable to establish trade with the Cherokees and that the Cherokees’ best interests lay with the British colonies. In an attempt to convince the British that he was not working in French interests, he raided against “French Indians,” killing eight Frenchmen and taking two prisoners. With the evidence of his triumph, he went to Charleston to meet with Governor Glen. His visit was successful, bringing a promise that trade conditions would be improved and a great many presents given. He told the governor that he was the spokesman for the Cherokee Nation.

Glen’s promise of improved trade was not fulfilled, and in 1754, with the threat of a war between France and England in the air, Virginia attempted to enlist the aid of the Cherokees. The meeting was friendly but unfruitful, so in the next year the Cherokees were again meeting with South Carolina. This time Ada-gal’kala persuaded Governor Glen to meet with him on the banks of the Saluda River, half the distance from Charleston. At this meeting, the governor again promised improved trade. He also promised a fort to be built in the Cherokee country for the protection of the women and children while the men were away at war. He said that he would send Ada-gal’kala and some other Cherokees to England. In exchange, Ada-gal’kala gave up Cherokee land and declared himself and his people “children of the great King George.” He said that his voice was “the voice of the Cherokee Nation.” The fort was not built.

Virginia became desperate in 1755, when General Edward Braddock’s army was defeated by the French. They asked for another meeting with the Cherokees, and at that meeting Virginia agreed to trade with the Cherokees and to build a fort. The Virginians built their fort in the Overhills in Tennessee. There were still pro-French Cherokee towns as well as persistent rumors from those towns that the British were preparing to march against the Cherokees. More meetings were held with both South Carolina and Virginia, and the wily Ada-gal’kala continued playing one against the other.

He had, however, developed a taste for rum, and on one occasion he went very drunk into Fort Prince George in South Carolina and made a motion as if he would strike Captain Raymond Demere, the fort’s commander, in the face with a bottle. Several of the Indians there took Ada-gal’kala away. The next day he apologized profusely to Demere for his behavior while drunk, blaming everything on the liquor.

The South Carolina fort was at last built and called Fort Loudon. Ada-gal’kala once again led a raid against the French and afterward visited Charleston, where he presented the governor with scalps. He complained again about some traders’ behavior, and one trader was placed on probation. The new governor did not, however, approve of the promised Cherokee visit to England. Back in Chota in Tennessee, Ada-gal’kala found that a Cherokee named Old Hop (see “Guhna-gadoga”) had been entertaining the French in his absence. He told Captain Demere that Old Hop was a fool who could do nothing without his help. And when Cherokees complained about the traders, he said that it was because they had allowed the French to come among them.

By 1758, Ada-gal’kala had become the most influential leader of the Cherokees. Old Hop still held the title, but everyone seems to have known the truth. Influential though Ada-gal’kala may have been, no one could exert absolute control over the Cherokees. Many Cherokee towns still acted as independently as ever. Although Ada-gal’kala met with the Virginians and even went on an expedition or two with them, other Cherokees were fighting with Virginians. Some Cherokees also killed South Carolina settlers. South Carolina governor William Lyttleton responded by restricting trade with the Cherokees once more. In 1759, Ada-gal’kala went on an expedition in Illinois against the French, presumably to show his unfailing support of the British.

In Ada-gal’kala’s absence, Ogan’sto’, the great war leader, and a number of other Cherokees went to Charleston to ask that the latest trade embargo be lifted. Governor Lyttleton had them surrounded and taken prisoner. Then he marched with a force of seventeen hundred men to Fort Prince George in South Carolina, taking the hostages along with him. When Ada-gal’kala returned from Illinois and heard what had happened, he marched to Fort Prince George with a British flag carried before him. Lyttleton met with him and demanded that the Cherokees who had killed Virginians be captured and turned over to him for punishment. Ada-gal’kala agreed, but said it would be very difficult, if not impossible. He managed to come up with two of the guilty Cherokees, and Lyttleton released two hostages.

Ada-gal’kala then persuaded Lyttleton that he could not convince the Cherokees to cooperate with him in the matter of the guilty Cherokees without the help of Ogan’sto’, who was one of the most powerful men in the nation. He managed to secure the release of Ogan’sto’ and a few others. Ogan’sto’, however, remained strongly anti-English for the rest of his life. Then an outbreak of smallpox frightened the governor back to Charleston. Ogan’sto’ lured the commander of Fort Prince George out of the front gate and had him fired on and killed. Inside the fort, angry soldiers murdered all of the Cherokee hostages. Around this same time, Old Hop died and was succeeded by his nephew.

Ada-gal’kala, possibly seeing events coming over which he could exercise no control or possibly attempting to escape the dreaded smallpox, took his family to the woods to live in isolation. Ogan’sto’ laid siege to Fort Loudon. When Major Archibald Montgomery was sent to the aid of the besieged in the fort, Ada-gal’kala traveled there to see what he himself could do to resolve the situation. When Montgomery was ambushed and lost 140 men, he said that he had accomplished his mission and left the country. Fort Loudon was still surrounded.

When Captain Demere at last surrendered and abandoned the fort, the Cherokees discovered that he had betrayed them by destroying guns and ammunition, contrary to an agreement the two parties had reached, and so they attacked the retreating British troops. Ada-gal’kala ransomed his friend John Stuart and led him to safety. He later brought out ten more survivors of the Fort Loudon siege. With Ogan’sto’ ready to take the Cherokees over to the French side, Ada-gal’kala became even more important to the British.

In retaliation for Fort Loudon, the British sent a force out of Charleston against the Cherokees. Led by Colonel James Grant, the troops went to Fort Prince George, where Grant had a meeting with Ada-gal’kala. Grant was not to be dissuaded from attacking the Cherokees, however, and before he was through, he had destroyed fifteen Cherokee towns, and many acres of corn and had driven hundreds of Cherokees into the mountains. Grant met with Ada-gal’kala once more to talk of peace. This time he was ready to come to some agreement, but he demanded that four Cherokees be turned over to him to be executed in front of his army. Ada-gal’kala met with Governor William Bull of South Carolina, and the governor agreed to strike out the clause about killing four Cherokees. The peace was concluded.

In 1761, Ada-gal’kala asked Governor Bull to make John Stuart the British Indian superintendent, but the governor replied that he did not have that authority. He did use his influence, though, and Stuart was appointed the following year. Then, with the news of the death of Uka Ulah that year, Stuart acknowledged Ada-gal’kala as the (sixth) principal chief of the Cherokee Nation because everyone knew that he was the real leader of the Cherokees anyway. The title principal chief was, of course, in recognition of the fact that there were many Cherokee chiefs, at least two for each town. This British appointment may or may not have been a rubber stamp for general Cherokee opinion. It was, however, a major step in the direction of modern nationhood and the role of a chief executive. At one point in his career, Ada-gal’kala even referred to himself as the president of the Cherokee Nation.

The year 1763 marked the end of the war between France and England. In 1767 and again in 1770, Ada-gal’kala gave up some Cherokee land to Stuart. White settlers were swarming onto Cherokee land. Seventy families settled along the Watauga River, running in North Carolina and Tennessee, where they became known as the Wataugans. Under British law (the Proclamation of 1763), they were forbidden to purchase Indian land, so they formed a plan to lease it. Stuart’s assistant, Alexander Cameron, agreed, and so did Ada-gal’kala. The land was leased for eight years.

In 1774, Ada-gal’kala seems to have made a private deal with the Transylvania Company, owned by Judge Richard Henderson and Captain Nathaniel Hart of North Carolina. Henderson and Hart, aided by Daniel Boone, proposed to purchase twenty million acres or so from the Cherokees, forming middle Tennessee and central Kentucky. Ada-gal’kala went to visit Henderson and Hart to inspect the goods to be traded. On January 1, 1775, with six wagonloads of goods, they headed for Sycamore Shoals on the Watauga River in northeastern Tennessee. The deal was concluded in March in spite of strong protestations from Ada-gal’kala’s own son, Dragging Canoe, from Cameron, and from Governor Dunmore of Virginia. The British objections were based on English law: Indian land could be purchased only by the king. The sal...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Entries A–Z

- Bibliographic Essay