This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

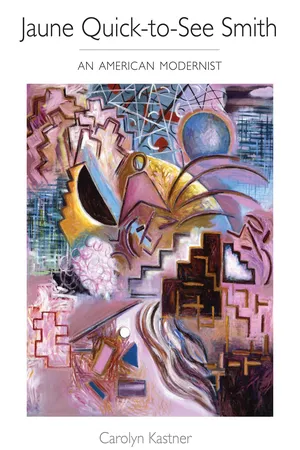

The first full-length critical analysis of the paintings of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, this book focuses on Smith’s role as a modernist in addition to her status as a wellknown Native American artist. With close readings of Smith’s work, Carolyn Kastner shows how Smith simultaneously contributes to and critiques American art and its history.

Smith has distinguished herself as a modernist both in her pursuit of abstraction and her expressive technique, but too often her identity as a Native American artist has overshadowed these aspects of her work. Addressing specific themes in Smith’s career, Kastner situates Smith within specific historical and cultural moments of American art, comparing her work to the abstractions of Kandinsky and Miró, as well as to the pop art of Rauschenberg and Johns. She discusses Smith’s appropriation of pop culture icons like the Barbie doll, reimagined by the artist as Barbie Plenty Horses. As Kastner considers how Smith constructs each new series of artworks within the artistic, social, and political discourse of its time, she defines her contribution to American modernism and its history. Discussing the ways in which Smith draws upon her cultural heritage—both Native and non-Native—Kastner demonstrates how Smith has expanded the definitions of “American” and “modernist” art.

Smith has distinguished herself as a modernist both in her pursuit of abstraction and her expressive technique, but too often her identity as a Native American artist has overshadowed these aspects of her work. Addressing specific themes in Smith’s career, Kastner situates Smith within specific historical and cultural moments of American art, comparing her work to the abstractions of Kandinsky and Miró, as well as to the pop art of Rauschenberg and Johns. She discusses Smith’s appropriation of pop culture icons like the Barbie doll, reimagined by the artist as Barbie Plenty Horses. As Kastner considers how Smith constructs each new series of artworks within the artistic, social, and political discourse of its time, she defines her contribution to American modernism and its history. Discussing the ways in which Smith draws upon her cultural heritage—both Native and non-Native—Kastner demonstrates how Smith has expanded the definitions of “American” and “modernist” art.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jaune Quick-to-See Smith by Carolyn Kastner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Monographies d'artistes. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Born in the USA

All of my work develops into a series with research, reading, and traveling—an ongoing process that stimulates ideas.

—Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Smith’s artwork is always contingent, conditional, and historical. She creates art as a medium for communication. Her own complex identity is the starting point, her target is the point of complexity in each viewer, and her goal is to create a moment of recognition, agitation, and, finally, comprehension. Visualizing and representing cultural identity is not the end in itself, but rather her method for pointing to the problem of representation—how an artist expresses specific and differing perspectives on history, gender, and the notion of race to incite response and action. She uses the broad visual vocabulary of modernism as an expressive tool and grounds her artistic practice in the history and production of modernism, though she is not interested in overturning one visual regime for another in search of a distinct signature style. The distinguishing characteristic of her art is her drive to communicate with the broadest possible audience on a subject about which she is passionate. In each work of art, Smith combines technique, style, composition, and color to articulate a message. Her goal is not to replicate, reproduce, or mimic, but to establish a common language as a starting point for communicating with her audience.

Modernism

Smith has distinguished herself as an American modernist in both her pursuit of abstraction and her expressive technique. At the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, where I am a curator, we define American modernism as a period from the late 1800s to the present. As Barbara Buhler Lynes, former curator and Emily Fisher Landau Director of the Research Center of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, explains, “We are still too close to what has gone on to set limits and boundaries on the meaning of American Modernism. As yet, there is no scholarly consensus about its meaning.”1 Modernism, as I use the term in this text, arose as a response to the increasingly urban, industrial, and secular society that emerged in nineteenth-century Western culture. Modern art is part of and expresses that discourse. The term modernism has come to be associated with art in which the traditions of the past have been discarded in favor of experimental techniques and practices. In general, the term modernism comprises the activities and artwork of those who felt that “traditional” forms of art were inadequate in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an emerging industrialized world. Since the nineteenth century, artists have rejected tradition and embraced change as they experimented with new ways of seeing and expressing their experience in their chosen materials. They have taken the position of the avant-garde, the “advance guard,” as they opened new cultural territory, even questioning the function of art. The history of that new art has been written largely as if it were one ever-continuing series of experimentation and response proceeding in a linear progression of styles.

Beginning with the tendency toward abstraction in the late nineteenth century, the avant-garde self-consciously preferred to be free of traditional standards of beauty and artistic practices. They began to choose the appearance and content of their work with the purpose of explicitly dismantling traditional modes of picture making. The working vocabulary of early abstract painters, such as Vassily Kandinsky, Joan Miró, and Paul Klee, emerged from experiments with color and composition. American abstract painters of the 1940s and 1950s, such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko, created visual fields to express themselves independently of language, to visualize an experience or an emotion nonverbally. The pop artists of the 1960s rejected the formalism of abstraction to make an art that was accessible, commercial, even banal. For example, the artwork of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein in the United States carried a specific American identity, a contemporary time stamp of the present moment that seemed to deny history. The practice of writing a history as a never-ending series of stylistic changes by artists who displace their predecessors emphasizes the new and privileges innovation as a creative goal and an end in itself. However, the categories of art historical discourse are imposed outside of and after an artist’s creation, usually pointing to new and distinguishing characteristics. Yet abstraction and pop as expressed in the early artwork of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns introduced concepts of the contingent and chaotic nature of contemporary culture even as they worked in an expressive mode. Unconcerned with identifying labels, these artists created new work by mixing styles and media and by painting abstractly even as they attached found objects to the surface of the canvas.2

By the time Smith entered graduate school in the 1970s, abstract expressionism and pop art were already history, like the early modernism of Kandinsky, Klee, and Miró. The diversity of modernism, the individualism of artist and style, and its cosmopolitan nature had been established as its identifiers. As artists have always done, Smith adapted what was useful to her to make art that was meaningful for her. Though her oil paintings have the facture and touch of abstract expressionism, her will to narrate is strongly present. She adapted the techniques but ignored the dictum of the nonobjective. In her Petroglyph Park series of the 1980s, she created an abstract visual field of fragmented, disorienting views of landscape even as she marked it with specific historical and political references. She freely chose to mix the brilliant color and lyricism of abstract painters who preceded her, such as Kandinsky, Klee, and de Kooning, while loading the surface with signs that tied the paintings to her personal heritage and to the landscape of New Mexico. She remarks: “Mixing abstraction with tribal motifs is hardly new, but it is a better way to communicate with a greater number of people.”3

In the Chief Seattle series of the late 1980s and 1990s, Smith began to appropriate the pop art technique of collage in the medium of found materials to further her political goal of communicating her fragmented and complex experience of being female, indigenous, urban, and a resident of the United States. Like her predecessors Rauschenberg and Johns, she takes advantage of the accessibility of popular icons and commercial materials to communicate with an audience who is already familiar with the ordinary and even clichéd visual language of popular culture. In 1992, she created a narrative series of thirteen panels, Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by US Government. In a parody of the pop culture icon the Barbie doll, Barbie Plenty Horses and her husband Ken are cast as trickster figures who survive to tell their own history. Smith says, “I appropriate pop art because it is symbolic of American mainstream culture. This gives me a common language in order to communicate with the viewer.”4 The notion of postmodernism recognizes this will to combine style and technique without reference to a particular time or narrative. As Smith observes: “There is a particular richness to speaking two languages and finding a vision common to both.”5

During the 1980s, young urban artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat expressed their dissent and independence by choosing style and media at will. They brought the aesthetic of the streets into art galleries, collapsing the boundaries of “high art” and the urban language of “graffiti.” Meant to be ugly and grotesque, these works confront complacent viewers. Art history wants neat categories and historical dividing lines, yet even before we used the term postmodern, artists were already picking their way through historical techniques and styles to marry them up with new forms and ideas about the nature of art. In her mixed media and pastel creations of the 1990s, Smith adapted the urban language of graffiti, displacing her previous bucolic references of prereservation freedom and replacing them with the expressive immediacy of drawn lines and fragments of found text, marks of the chaos and anxiety of the late twentieth century. Smith exploits a range of artistic styles and media in each new series to communicate with her audience. The medium she uses is always part of her message, and so are her chosen style and technique.6

Smith expresses her own perspective on the ever-changing horizon of modernity as she challenges viewers to keep up. She offers a familiar figure, a particular style, or a recognizable landscape as an invitation to viewers to look closely and find themselves within the complexity of her work. However, as quickly as identity is established, difference emerges: an abstract painting is punctuated by moments of figural recognition, or a pop culture icon is appropriated to tell an unfamiliar indigenous story, strategies which disorient the viewer and incite questions, not answers. Her effort to balance identity and recognition within the unfamiliar, the new, the threatening makes a problem for the viewer, who wants a narrative, not a question. What does an ancient petroglyph figure mean when it is painted across an abstract painterly surface? Why is Barbie telling indigenous stories of dislocation and loss? Why is the snowman red, not white?

A Distinct Modernism

Smith’s personal identity and experience as well as the political and cultural history of the people of the Salish Kootenai Tribe are expressed as visible signs of difference in her modernist artwork. Inspired by her Sqelix’u, Métis (French and Cree), and Shoshone ancestors, she is proud of her cultural heritage, whose roots reach deep and wide in Montana soil, even though she has lived and worked in New Mexico since 1976. Smith remembers a complicated childhood. Abandoned by her mother, she was raised primarily by her father, Arthur Smith. A rodeo rider, horse trader, and trainer, Smith’s father sometimes took her with him on his extensive travels, but she was also separated from him for extended periods as she lived in foster homes. She knew hard work for wages at an early age.

Like her father, the trader, Smith has a profound respect for the process of trading and communicating cultural values and ideas. She draws on the imagery and cultures of the Plateau region, where cultural exchange has a long history among the tribes of that territory. Smith expands the boundaries of American art as a cross-cultural bricoleur who self-consciously employs her training in Euro-American artistic traditions to express the particular experience of her birthplace and cultural heritage. Memories specific to her Sqelix’u heritage are a part of her visual vocabulary. Vests, canoes, war shirts, and women’s dresses add narrative context to her paintings and prints. The 1996 painting entitled Flathead Vest: Father and Child articulates the continuing interplay of Smith’s memories and her artistic interests (plate 2). Though time and distance separate the artist from her past, this artwork expresses how her creativity grows from the culture of her ancestors. Like a journal, the canvas receives the artist’s actions and reflections. Fragments of text from recent editions of her tribal newspaper, the Char-Koosta News, and photographic images ruptured from the past collide on the surface. Contemporary news from the Salish Kootenai Tribe and pictures from a bygone era merge on the canvas, like thought and memory in the artist’s mind. As viewers, we are offered both an emotional and a historical context for the specific vocabulary that grows from Smith’s cultural roots in Montana.

Smith credits her father’s aesthetic and their exchange of drawings for her first understanding of art. She has vivid memories of watching him at work creating a home, its roof, and fences. “I learned the process of making art and about aesthetics from my father. In early memory, I watched him split shingles for our cabin and cover the walls in careful rows. This was beautiful to me. I drew on his discarded shingles, and he hung one by his bed—a tribute to my work which spurred me on. At another time we built corrals together. To this day they remain some of the most splendid sculpture I’ve ever seen. Watching my father run his hands over a horse to read its history; watching him braid lariats; sharing his collection of beadwork and pestering him to draw a sketch of an animal so I could carry it in my pocket—all this and more taught me to see and feel. This is my beginning in art, not the Euro-American academic museum enshrined art— but the real stuff of which art is made—seeing and feeling.”7 Drawing is another early memory for Smith. “I always drew. I remember drawing on dirt with sticks and with my hands. Drawing has always been natural to me.”8

By the age of thirteen, Smith visualized a more specific artistic identity in the tradition of Frenchman Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, complete with palette and brush, beret and beard (plate 3). A 1953 picture of Smith, recorded by a neighbor she remembers as Mr. Jarvis, demonstrates that she had no difficulty in grafting this foreign and masculine notion of an artist onto her cultural roots in Montana. Captivated by José Ferrer, the actor who played the famous artist in John Huston’s 1952 film Moulin Rouge, Smith adapted her identity to fit the artist’s, as portrayed by the actor. She knowingly kneels before the camera, indicating her awareness of the artist’s small stature. Without hope of growing facial hair, she creates a moustache and goatee with the aid of axle grease.9 She is already a hybrid figure expressing her talent for joining conflicting cross-gender and cross-cultural symbols as she invents herself as an artist for the camera. Undaunted by the visible inconsistencies of difference (her gender or the rural setting), she makes her aspirations transparent as she prominently holds a brush and palette.

Five years later, in 1958, she enrolled in her first art classes at Olympic Colle...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One Born in the USA

- Chapter Two Seeing Red: Indigenous Identity and Artistic Strategy

- Chapter Three American Modernism and the Politics of Landscape

- Chapter Four Chief Seattle:Visualizing Environmental Disaster

- Chapter Five The Discourse of Modern Art in a Post Columbian World

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index