This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

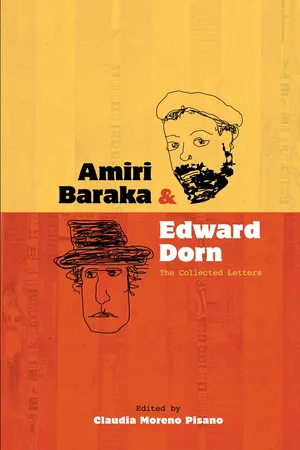

From the end of the 1950s through the middle of the 1960s, Amiri Baraka (b. 1934) and Edward Dorn (1929–99), two self-consciously avant-garde poets, fostered an intense friendship primarily through correspondence. The early 1960s found both poets just beginning to publish and becoming public figures. Bonding around their commitment to new and radical forms of poetry and culture, Dorn and Baraka created an interracial friendship at precisely the moment when the Civil Rights Movement was becoming a powerful force in national politics. The major premise of the Dorn-Jones friendship as developed through their letters was artistic, but the range of subjects in the correspondence shows an incredible intersection between the personal and the public, providing a schematic map of what was so vital in postwar American culture to those living through it.

Their letters offer a vivid picture of American lives connecting around poetry during a tumultuous time of change and immense creativity. Reading through these correspondences allows access into personal biographies, and through these biographies, profound moments in American cultural history open themselves to us in a way not easily found in official channels of historical narrative and memory.

Their letters offer a vivid picture of American lives connecting around poetry during a tumultuous time of change and immense creativity. Reading through these correspondences allows access into personal biographies, and through these biographies, profound moments in American cultural history open themselves to us in a way not easily found in official channels of historical narrative and memory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Amiri Baraka and Edward Dorn by Claudia Moreno Pisano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Letters. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Letters

I

1959–1960The LeRoi Jones-Edward Dorn correspondence begins with a request, from Jones in New York to Dorn in Santa Fe: “I’d like to have a couple of poems.” The poetry is the starting place, the central point around which these artists’ lives revolved. The letters from these first two years make clear how quickly the two poets realized their friendship, levels of ease in conversation belying their short acquaintance. They began to share their poetry, to share admiration and argument around these poems, to quickly make connections for each other with the many poets in their many circles of friends.

The correspondence has a definite ebb and flow, letters flying back and forth as quickly as once or twice a day while sometimes several weeks pass without a word. The letters work along many lines, from solidifying friendship to contact against loneliness to development as a writer. In a 1972 interview, Dorn said that getting assignments, so to speak, as you mature as a writer is incredibly important. Assignments are something you want and need in order to keep growing: “[I]n fact, the more you mature as a writer, the less you want to invent your own products and the more you want to be given them, to show what you can do” (Views 16). In a very real way, the letters serve as this kind of assignment—the audience, the response, and give and take of a written conversation is part of the thrust of the writing itself. Dorn and Jones are proving themselves to one another—testing the limits of their poetry and ideas and doing so against worthy partners. “LeRoi was, when I lived in Pocatello, my main correspondent in the East and I wrote him a lot—weekly, at least, sometimes a couple times a week. . . . [I]t was more than friendship” (Interviews 21).

In these first two years Dorn and Jones began their process of observing, worrying, and grappling with the unfolding of the late ’50s into the early ’60s: “So this was a time of transition. From the cooled-out reactionary ’50s, the ’50s of the Cold War and McCarthyism and HUAC, to the late ’50s of the surging civil rights movement” (Baraka Autobiography 189). Here are conversations from the ground.

“ ” “ ”

The list of poets and little magazines in Jones’s letter sets the stage for the heart of the Lower East Side poetry scene in New York City. In 1959 Jones and his wife Hettie were already editing, writing for, and printing Yugen, and there were often parties and gatherings in their home attended by the many poets, painters, and actors living in and visiting New York. Hettie Jones notes,

From a quick first look at Yugen 4 you’d say Beats, as the three Beat gurus—Kerouac, Corso, and Ginsberg—were represented. Except the “New consciousness in arts and letters” was more inclusive. Like Basil King, Joel Oppenheimer, and Fielding Dawson, the poets Robert Creeley, John Wieners and Charles Olson were out of Black Mountain College, where Olson was the last rector. Frank O’Hara, like the painters he knew, was a poet of the “New York School.” Gilbert Sorrentino lived in Brooklyn, Gary Snyder in Japan, Ray Bremser in a Trenton, New Jersey, prison. (74)

The Allen G. in this letter is, of course, poet Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997), a great facilitator in mixing circles of artists, introducing everyone he knew to one another. That sometimes worked the other way around though: it would be Jones who first introduced Ginsberg to Langston Hughes. Jones and Ginsberg began their own friendship when Jones moved to the Lower East Side: “I wrote to [him] at Git le Coeur in Paris when I moved to the Lower East Side asking him was he for real on a piece of toilet paper. He replied he was but he was tired of being Allen Ginsberg. He used a better grade of toilet paper.”

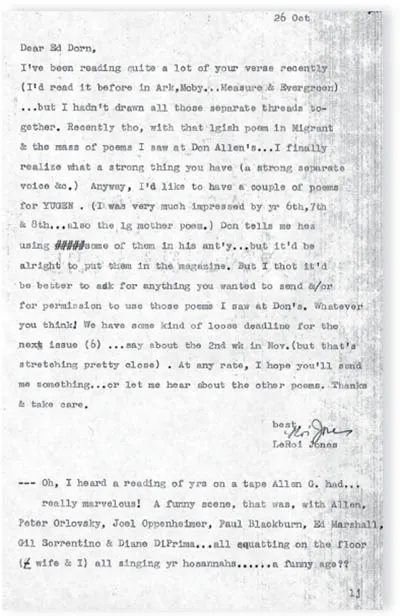

26 Oct [1959]

Dear Ed Dorn,

I’ve been reading quite a lot of your verse recently (I’d read it before in Ark, Moby . . . Measure & Evergreen) . . . but I hadn’t drawn all those separate threads together. Recently tho, with that lgish poem in Migrant and the mass of poems I saw at Don Allen’s . . . I finally realize what a strong thing you have (a strong separate voice &c.) Anyway, I’d like to have a couple of poems for YUGEN. (I was very much impressed by yr 6th, 7th & 8th . . . also the lg mother poem.) Don tells me he’s using some of them in his ant’y . . . but it’d be alright to put them in the magazine. But I thot it’d be better to ask for anything you wanted to send &/or for permission to use those poems I saw at Don’s. Whatever you think! We have some kind of loose deadline for the next issue (6) . . . say about the 2nd wk in Nov. (but that’s stretching pretty close). At any rate, I hope you’ll send me something . . . or let me hear about the other poems. Thanks and take care.

best, LeRoi Jones

—Oh, I heard a reading of yrs on a tape Allen G. had . . . really marvelous! A funny scene, that was, with Allen, Peter Orlovsky,2 Joel Oppenheimer,3 Paul Blackburn,4 Ed Marshall, Gil Sorrentino5 & Diane di Prima . . . all squatting on the floor (+ wife & I) all singing yr hosannahs. . . . . . a funny age??

Lj

Charles Olson’s Projective Verse was a small treatise on the nature of poetry and language, originally published in 1950 and reprinted by Jones’s Totem Press in 1959. This essay proved to be a powerful influence on the many poets who read it, opening up the restrictions, regulations, and boundaries within which mid-twentieth-century American poetry found itself confined. Olson talked about the poem’s connection to the breath, recognizing the poem to be a living entity integral to the world at large rather than a function of staid academic rigmarole. Poets responded wholeheartedly to Olson’s decree that “verse . . . if it is to be of essential use, must, I take it, catch up and put into itself certain laws and possibilities of the breath, of the breathing of the man who writes as well as of his listenings.”

It seemed to Dorn, though, that many poets didn’t quite understand what Olson meant. In a 1977 lecture at the Naropa Institute called “Strumming Language,” Dorn said, “I never thought that his discussion of the breath was meant to be taken as a way you could write poetry. I always thought it was meant to suggest to you that you could get involved physically with the poem in a way that, up to that point, hadn’t actually been suggested. . . . But, for anybody who thought that it was meant to function in a way that a VW manual will tell you how to set the valves, I just never took it that way.” Projective Verse found its way into the many circles and schools of poetry burgeoning in the ’50s and ’60s and continues to be a key text for understanding the history of American poetry.

5:XII:59

Dear Ed Dorn:

Finally looked at those poems of yours again, & I think 6th & 7th “Communications” wd do us best this time. Both, very fine. Your clear & marvelously exact images are really good news. That communication about that large woman or such I really dug, but space is always the kicker in this small shot business. But anyway, I’d like to use a couple more for the next Y6 (after one this month). #7 (if we can hold). #6 as I see it ought to make it later on in December. Or maybe we’ll get pushed into the sixties. (Wow, isn’t that straight out of some science fiction hash . . . THE SIXTIES. . . . I mean, where are the goddam anti-gravitators &such. Maybe we lived too soon anyway. Poo)

Saw Olson last wkend. Spent 3 days up there in froze Gloucester. But lovely to see Chas again. We (totem pr) just finished doing Proj Verse (reprinting the original article plus a supplementary letter from Olson) last night it arrived. Salud! When I get the whole batch in I’ll send on a copy.

Ok, well . . . NY cold & blue (like the negroes sing) eery like . . . but this is only time sensible person shd live here. Autumn & winter (well, ok, spring too) but summers are out. No woods or anything, but staring all day out at Hudson can be a real kick . . . anyway, you take care &c. & when you think of it send a poem or two??

best, LeRoi Jones

John Wieners (1934–2002) was a Boston-born poet, connected by art and friendship to many circles of poetry, including the San Francisco Renaissance and the Beats. He studied at Black Mountain with Charles Olson and poet Robert Creeley in the mid-1950s. Wieners edited and published three issues of Measure, an important small magazine. An active fighter in the gay liberation movement, a political activist, and involved in several publishing cooperatives, Wieners also struggled throughout his life, suffering through institutionalization in a psychiatric hospital by the hands of his family as a young poet. His struggles caused great pain for his friends and fellow poets: “[He] was a gem who flickered in and out of our lives. Our hearts. John’s story was tragic, but familiar, too. His Boston Catholic family had had him committed for being gay, and using dope, and maybe junk, now, all those shock treatments later, he was more than a little crazy” (Di Prima Recollections 273). Jones laments Wieners’s state in this letter to Dorn.

Irving Rosenthal (b. 1930), who Jones notes here as a possible help to John Wieners, was an editor for the Chicago Review and a writer himself, a great supporter and enthusiast for the emerging poetry of mid-twentieth-century America. He was willing to publish what others wouldn’t, including the first chapter of William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch in the Spring 1958 issue of the Review. The printing of this chapter of a book even Allen Ginsberg claimed was certainly too risqué to find a publishing home in the United States at the time caused great upheaval and no small backlash. An article titled “Filthy Writing on the Midway” in the Chicago Daily News ended up with the resignation of Rosenthal, Paul Carroll, and three other editors of the Review after the administration refused to publish the Autumn 1958 issue, in which would have been printed the second chapter of Naked Lunch along with a slew of Beat, San Francisco Renaissance, and other new poets. Rosenthal and the rest would go on to found Big Table, an independent magazine of poetry and the arts; they took the unpublished material from the Autumn issue of the Chicago Review for their first issue of Big Table.

19:1:60

Dear Ed Dorn,

Sorry for long silence but I’ve been on my back, suffering from evil combination of debauchery, bad lungs & probably malediction. Also, I don’t remember whether I sent those books I mentioned or not, so I’m sending them now (under separate cover).

Thanks for letting me see that poem (The Pronouncement) . . . really liked it. Your materials move right . . . or you handle them like statements about things (rather than filmy abstractions of the floppy tie school of poets &c.) Yass, if we could always keep talking about things, rather than just writing, cd stretch our materials (& our gruesome limitations: each is only where he is, no quick materialization to other lives: I mean, we can only write about what we know . . . which, you bet, is a definite limitation. “KNOW thyself.” OH what bullshit. LOSE thyself works just as well I’m certain. Anyway, all lovely poem, & I’d like to see any you want to send . . .

Magazine (#6) is slow because of my flabbiness. Physically & mentally. I move faster now . . . & prospects are good for early February. This one is larger, 52 pages, & is painful process to do.

Oh, I also included a book of Max Finstein’s7 in pkg . . . thot you’d be interested in. John Wieners was by here a couple of weeks ago. Stayed with us for week or so. He’s in terrible shape. Sullen silent . . . never saw him like that before. Very disturbed (??) And that’s a terrible way to try to say it. Disturbed??? Like who isn’t? When John left N.Y., he went up to his parents in Boston. His mother apparently flipped and called up the mental hospital people. They came & from what I get from Irving Rosenthal, they carried John off in straight jacket. He’s got to stay in that place at least 40 days, cause his mother signed him in. Seems so bleak . . . but Ivg wants to get some kind of writ to get John out under his care. Hope so. Otherwise very bleak.

Big Table 4 sounds, for the most part, like a good idea; tho I differ with P. Carroll8 in that Gawd knows there’s too much good poetry around now to confine it to some SPECIAL issue. Shit, why ain’t he (Carroll) just publi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Letters

- References

- Index