eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

The Migrant Project

Contemporary California Farm Workers

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

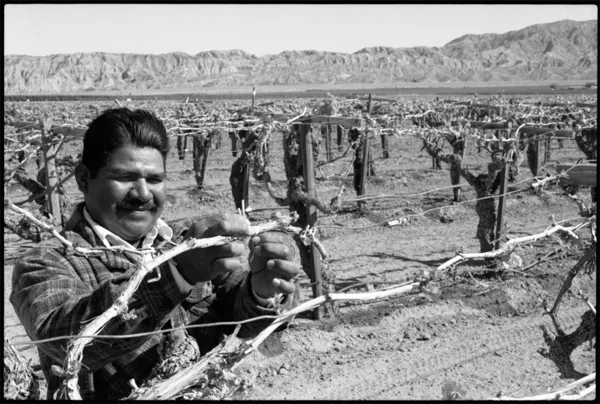

The images in this book highlight the lives of the men and women who struggle to exist while literally feeding this country. Countless words and studies over decades bemoan the plight of those who toil in the fields, but Rick Nahmias's pictures bring farm workers to us in an unforgettable way, taking us beyond stoop labor stills and into their intimate moments and inner lives. Having traveled over four thousand miles to document California's migrant workforce, Nahmias's soulful images and incisive text go beyond one state's issues, illuminating the bigger story about the human cost of feeding America.

The Migrant Project includes the images and text of the traveling exhibition of the same name, along with numerous outtakes and an in-depth preface by Nahmias. Accompanied by a Foreword from United Farm Worker co-creator Dolores Huerta, essays by top farm worker advocates, and oral histories from farm workers themselves, this volume should find itself at home in the hands of everyone from the student and teacher, to the activist, the photography enthusiast, and the consumer.

Every day in the hot fields of California, hundreds of thousands of farmworkers toil for long hours at low pay to provide fruit and vegetables to feed our nation. Most Americans never see the faces of these hard-working men and women, and know little or nothing about the harsh conditions they endure. The Migrant Project has done an extraordinary job documenting these workers' lives. Rick Nahmias's powerful photographs and the beautiful essays of dedicated advocates tell an inspiring story of the farmworkers' historic struggle for the respect, the dignity, and the justice they so obviously deserve.--U.S. Senator Edward M. Kennedy, Massachusetts

Nahmias's images starkly capture both the humanity of the farm workers who literally feed our country, and the inhumanity of a system which has kept them and their predecessors prisoners to poverty for decades. This book is a testament to the flesh-and-blood cost of feeding America.--Arianna Huffington, author, editor-in-chief of The Huffington Post, and nationally syndicated columnist

University of New Mexico Press gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution of the Columbia Foundation toward the publication of this book.

The Migrant Project includes the images and text of the traveling exhibition of the same name, along with numerous outtakes and an in-depth preface by Nahmias. Accompanied by a Foreword from United Farm Worker co-creator Dolores Huerta, essays by top farm worker advocates, and oral histories from farm workers themselves, this volume should find itself at home in the hands of everyone from the student and teacher, to the activist, the photography enthusiast, and the consumer.

Every day in the hot fields of California, hundreds of thousands of farmworkers toil for long hours at low pay to provide fruit and vegetables to feed our nation. Most Americans never see the faces of these hard-working men and women, and know little or nothing about the harsh conditions they endure. The Migrant Project has done an extraordinary job documenting these workers' lives. Rick Nahmias's powerful photographs and the beautiful essays of dedicated advocates tell an inspiring story of the farmworkers' historic struggle for the respect, the dignity, and the justice they so obviously deserve.--U.S. Senator Edward M. Kennedy, Massachusetts

Nahmias's images starkly capture both the humanity of the farm workers who literally feed our country, and the inhumanity of a system which has kept them and their predecessors prisoners to poverty for decades. This book is a testament to the flesh-and-blood cost of feeding America.--Arianna Huffington, author, editor-in-chief of The Huffington Post, and nationally syndicated columnist

University of New Mexico Press gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution of the Columbia Foundation toward the publication of this book.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Migrant Project by Rick Nahmias in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Essays and Oral Histories

Alberto Juan Martinez:

An Oral History

Anna Lisa Vargas, Oasis, CA, January 21, 2007

I came from Misantla II, Veracruz, Mexico, at the age of thirty-seven, with the intention to better my situation in life and that of my family. Many of my co-workers came here in 2000. I too followed, and with a lot of sacrifice, I made it.

Growing up, I didn’t have the opportunity to finish school. I completed the fifth grade where I excelled in math. It was the hope of one of my teachers that I continue my education and attend middle school. When he approached my parents, my father did not agree and instead felt that I should begin to work. As well, the middle school that I would be attending was an hour away from my hometown. (It was only later, at the age of twenty-five, that I attended adult school for over two years and was able to complete the equivalency of a middle school education.)

I decided to come to this country because I knew that I could make a little more money than I was making in Mexico. At first I came alone and had to abandon my family. In Veracruz, I would earn about sixty pesos (approximately five U.S. dollars) a day, and it was insufficient to survive. I laid bricks. That’s very tough work, and my wife would help by mixing the cement when I would get work like putting up a wall or building a house. I also did other work such as deforesting, removing grass with a machete, and caring for animals. Ultimately, I decided to come to this country because life was just too poor in the south of Veracruz.

All of us were aware that people have died in the desert or that the coyotes sometimes abandon people on the way, but I decided to come anyway. A group of us crossed on foot without a guide or any help. Simply, a friend had returned to Mexico and had told us how it was done.

We were in Mexicali, and had been dropped off near the edge of the city. We came in three groups. It was about one in the morning when the Border Patrol caught us. They took us back across the U.S.-Mexico border and made us throw away the food we had brought in our backpacks. Our first attempt failed, and we were then taken somewhere past the Colorado River. Two days later we tried for a second time, and again we were caught by the Border Patrol while attempting to cross a canal. I had no money and had to begin working in Ensenada. The little earnings I made were sent to my family. I had been working there for about a month when we attempted to cross the border for a third time but ultimately had no luck.

We then got in contact with a man who was from the same town of origin as me. He helped us find a person who knew the way and who was able to pass us by train to California. That’s how we arrived. Soon after, I began working as an agricultural worker in the Coachella Valley. After about seven months I began to notice there were women working as well. It was then my intention to bring my wife over. It didn’t make sense, her being back home with the situation the way it was—no work. I told her that she could come work, since the jobs here are easy and more plentiful.

So, I returned to Veracruz in 2001 for my family. I brought my fourteen-year-old son, Cesar, who began working the fields right away, and soon after the rest of my family followed. My son and I began in the grapes, where we continue to work. First, comes the pruning (la poda), then leaf pulling (el deshoje), when a lot of little sprouts appear and you have to remove the excess leaves so that there is enough space for the bunches of grapes to grow. Next is el desbonche, in which you have to remove any extra bunches of grapes to ensure that approximately twenty-five bunches remain per vine. This gives the vines a nice shape and allows them to produce about fifty bunches of grapes. Then, finally, comes the picking of the grapes (la pisca).

I think we as workers suffer a lot because one always has to be working. The supervisor wants to make sure that output is good. He is constantly saying “the cost, the cost” of the product. If one doesn’t put in a lot of effort then the prices go up for the consumer. The foremen explained to us that if the cost of picking the crop is too much, then it will go up at the time of sale. I have to focus on pushing myself to try and maintain a low cost for the consumer. You have to push yourself to the limit to complete the job. It’s what is required and what the supervisor wants.

Workers who have been here longer will say, “Don’t work fast, the owners already have money,” or “Why are you working fast just for them?” They don’t realize that while they’re not working, the rest of us have to work a lot harder so that the crew completes the job. The foreman will take away our block (our allotted section of work) if the crew doesn’t produce enough and we then have to look for work elsewhere. If that happens, then for one or two days I earn nothing. Sometimes you don’t even know who the supervisor is. Many times, I’ve worked an entire day without pay when the output turns out to not be enough. The foreman would send us to another block and pay us for only a day or two of work instead of for all the work we actually did. That happens often, even when I’ve worked to the best of my ability.

There are some days that are very difficult, like when it’s very hot and the dust from the grapevines gets all over your body. I used to think it was dirt but then learned it is sulfur used to help ripen the grapes. This dust really irritates your skin. Even after I would get home, take a shower, and change my clothes, it still irritated my skin. At night, I still would itch. It makes you not want to return to the fields the next day but you have to. It’s your job.

When the grapes are almost ripe, they apply sulfur more frequently, about once or twice a week. Normally, the foremen don’t tell us to cover ourselves up. They just tell us not to eat the grapes because they have been sprayed. The men normally don’t cover up, but once I saw a man with his face covered, and the contractor asked him, “Why are you covering your face? Only women cover their faces.” So from then on, no one covered his or her face. Only during the pruning would they give us safety equipment, but after that, nothing.

During the removing of leaves, it’s really important to work hard since it is then that the foreman makes an estimate to determine how much each grapevine should cost the grower to harvest. The amount you pick and the work that needs to be completed is what’s important to the foreman, not the health of the worker. There is a lot of dust released from the plants when you are removing leaves, and you get completely covered in it. You have to work fast in order to get all the work done, and you can’t be worried about how much sulfur you are inhaling. You just have to keep going.

It doesn’t matter to the supervisor if something urgent comes up, or if you had already asked for the time off. The boss will say, “No, we need to finish today,” or, “We need to work on another block tomorrow.” At times we work the normal eight hours, but at other times we have to work for nine or ten hours. Even if the workers do not want to work overtime, we must or else risk not getting hired the next time. You learn to be very compliant with what the supervisor says.

I think, there needs to be improvements in the worker’s salary, so that it’s enough to cover all your expenses. Normally, when you arrive, with the little you make, you need to pay off the person who helped you get across. Many people get a loan in their town of origin in order to get here or pay off the coyote. Therefore, the little earnings you make here go to paying off that loan and sustaining your family. Aside from that you have other expenses, like rent, which is expensive.

Sometimes when you rent a place to live there is no concern about the living conditions. Landlords simply place people anywhere. At times, there would be eleven of us to a room. Finding housing when there is none is one of the difficulties. So, you are forced to stay in cramped rooms. There is no other choice. The landlord is the one who profits because he can rent out one room to five people. At one hundred dollars per person, that’s five hundred dollars, simply for renting a single room. So, if you decide to live a little more comfortably, then it’s two hundred to three hundred dollars per room, and it turns out to be more expensive.

As long as there is agriculture here in the Coachella Valley, there will always be people coming to work. For example, there are currently many people arriving in Coachella from Salinas because it is the harvest season here, but there is no housing so they have to live under the same circumstances—many people to a single room. Sometimes you can’t even take a shower when you get home from work or cook, and you just can’t live that way. I would say that building more housing for migrant farm workers is required—places where we can live with some small amount of comfort.

I became a Promotor Comunitario because I took a great interest in achieving social justice for my community. A Promotor Comunitario as defined by the Poder Popular Program is “an agent of change, a community health ambassador, and a community advocate.” A Promotor is a source of information who seeks to educate community residents to be better informed, empowered, and have greater control of their communities’ resources and policies.

There are a lot of inequalities and problems for migrants, therefore we need the community to become more involved and learn about how to exercise its rights. We need to create resident-driven committees where improvements and changes can be made. I would like to see the workers utilize the services that already exist. I mention certain services to my co-workers, but often they’d rather go to work than attend a meeting or an event that will better inform them. This happens because if they lose a day of work that will affect them right now. They need to work. Even if we are were sick, we’d rather receive the earnings for the day.

When I first began working here, I had an ear infection and a fever. I could barely hear. I worked that way for about two weeks until finally I couldn’t bear the pain anymore. I did this in order to send money to my six children. I know many who do this. Even if they are ill, they still go to work. Since many have children in Mexico, about every week they send money home to them. So even when I tell them about our community meetings in the evenings and how important they are they say, “I need to earn money for my children so they can eat.” Sometimes I feel that way as well, since I have my own family.

During the last few weeks we have only been able to work three days a week, for about five hours per day—or fifteen hours a week total. We should be working forty hours a week, but because of the recent freeze a lot of crops got ruined. Right now we are replanting baby bell peppers. I am also working in the artichoke fields and with other vegetables. The supervisors are sending us to do other work because the bell pepper season has been cut short as well. We are also removing rocks and weeds from the fields, so it will be clean during the replanting. I currently earn seven dollars an hour.

My two oldest children, Lucia Ester (age twenty) and Cesar (age eighteen) also work in the fields. They help me support the rest of the family. They chose not to continue with their education. We didn’t have a way to support their studies. In Mexico, Lucia and Cesar only completed middle school. The rest of the children have continued their studies here. I decided to bring my whole family to the United States so this could happen—so my children would finish school and have a better chance to find a good career. In Mexico they could receive an education but there are not many jobs available. I have cousins in Mexico who have college degrees, and unfortunately they still have to work odd jobs. I tell my younger children that they need to make the effort in order to make it to a university and attempt to receive scholarships because they have told us that the cost of attending a university is very high. My hope is that they will make it, and I tell them to work hard. I don’t ask much of them—just to concentrate and do well in school. I see that they really are trying.

I hope they will do well and attend a university so they can have a better job than thos...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- The Migrant Project: Contemporary California Farm Workers

- Essays and Oral Histories

- Acknowledgments