This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

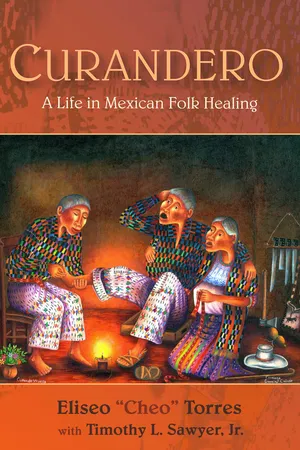

Curandero

A Life in Mexican Folk Healing

About this book

Eliseo Torres, known as Cheo, grew up in the Corpus Christi area of Texas and knew, firsthand, the Mexican folk healing practiced in his home and neighborhood. Later in life, he wanted to know more about the plants and rituals of curanderismo.

Torres's story begins with his experiences in the Mexican town of Espinazo, the home of the great curandero El Niño Fidencio (1899-1939), where Torres underwent life-changing spiritual experiences. He introduces us to some of the major figures in the tradition, discusses some of the pitfalls of teaching curanderismo, and concludes with an account of a class he taught in which curanderos from Cuernavaca, Mexico, shared their knowledge with students.

Part personal pilgrimage, part compendium of medical knowledge, this moving book reveals curanderismo as both a contemplative and a medical practice that can offer new approaches to ancient problems.

From Curandero

. . . for centuries, rattlesnakes were eaten to prevent any number of conditions and illnesses, including arthritis and rheumatism. In Mexico and in other Latin American countries, rattlesnake meat is actually sold in capsule form to treat impotence and even to treat cancer. Rattlesnake meat is also dried and ground and sprinkled into open wounds and body sores to heal them, and a rattlesnake ointment is made that is applied to aches and pains as well.

Torres's story begins with his experiences in the Mexican town of Espinazo, the home of the great curandero El Niño Fidencio (1899-1939), where Torres underwent life-changing spiritual experiences. He introduces us to some of the major figures in the tradition, discusses some of the pitfalls of teaching curanderismo, and concludes with an account of a class he taught in which curanderos from Cuernavaca, Mexico, shared their knowledge with students.

Part personal pilgrimage, part compendium of medical knowledge, this moving book reveals curanderismo as both a contemplative and a medical practice that can offer new approaches to ancient problems.

From Curandero

. . . for centuries, rattlesnakes were eaten to prevent any number of conditions and illnesses, including arthritis and rheumatism. In Mexico and in other Latin American countries, rattlesnake meat is actually sold in capsule form to treat impotence and even to treat cancer. Rattlesnake meat is also dried and ground and sprinkled into open wounds and body sores to heal them, and a rattlesnake ointment is made that is applied to aches and pains as well.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Curandero by Eliseo “Cheo” Torres,Timothy L. Sawyer,Eliseo "Cheo" Torres,Torres Eliseo “Cheo” in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medicine Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Medicine BiographiesONE

The Awakening

Espinazo, Mexico, is not a prominent place—not on world maps, not on maps of Mexico, not even on maps of the state in which it is located, Nuevo León. Its name means spine, and it refers to the backbone of an animal, a metaphor that comes from a long, jagged ridge running along one of the town’s horizons. Most days this animal spine can be seen profiled against a brilliant azure sky, for Espinazo does not receive a great deal of rain. Espinazo is not a large place, the home of maybe a few hundred souls, most of whom have enough to get by on but little more. It is a quiet country village, a desert town on a high plateau, surrounded by mountain ranges, sage-brush country, and arid expanses filled with an abundance of the hardscrabble natural life that exists only in deserts—snakes, lizards, and cacti. The town itself is home not only to the rural people who live there, it is also home to much livestock—sheep, goats, chickens, and cattle—and barnyard smells suffuse the air, as well as the aromas of good cooking.

Twenty years ago or so I was poised on the edge of several great personal discoveries because of this insignificant dot on the map of Mexico. I had been hearing about Espinazo for a long time from friends and acquaintances who knew of my personal and professional interest in curanderismo, the art of Mexican folk healing. Curanderismo, as it is practiced along the U.S.-Mexican border, the Southwest part of the United States, most of Mexico, and in many other parts of Latin America, is an ancient, fabled, rich tradition which has much to teach modern, conventional medicine about illnesses and their cures.

I had grown up in the United States in a rural Mexican-American community in South Texas, next to Corpus Christi, not far from Houston, Texas, and the Gulf of Mexico. While I was growing up, I gained extensive first-hand experience of the long and storied heritage of curanderismo, because my own family was versed in the rituals, knowledge, and practices of our folk-healing tradition. My mother and father told us many stories about legendary healers, and they were themselves minor practitioners of the healing arts, employing knowledge that had been handed down from time out of mind in the Mexican-American border communities, where much of the centuries-old culture of Old Mexico still survives.

I grew up in an atmosphere, then, full of the magic, the religiosity, the simple faith of a proud people who had often lived hard lives but who still had a strong sense of who they were, and of their connection with a past that partook both of ancient sciences and ancient faith. The connection with Old Mexico I remember as palpable, and I could feel in my own background as I was growing up the great traditions of the Mexican indigenous peoples, including the Aztecs and Mayans who had contributed much to modern curanderismo. I was also deeply aware of another connection, to the Old World of the Spanish Conquistadores and of their own link with ancient Arabic traditions through the Moors, who had ruled Spain for centuries and who also bequeathed, via the Spaniards, much knowledge to what exists now as Mexican folk healing.

All of these things were a deeply ingrained part of me from an early age. And so, as I grew up and began to pursue higher education, I settled on the folk healing traditions of my people as the natural focus of my studies, and I did much research and wrote about curanderismo, eventually getting a doctoral degree in my home state of Texas—a proud moment for me and for my family, since I had grown up in a remote rural community far from colleges and universities and other modern conveniences, and since I was the first member of my family to reach this level of achievement.

As I settled into my academic career, and continued with my research into curanderismo, I heard from more and more people farther afield about different aspects of this arcane field of study. Many people of both Mexican and non-Mexican heritage were fascinated by curanderismo, I think partly because of its implications for conventional medicine. A growing respect in America and in the world at large for the ancient wisdom of rural, folk traditions, and of indigenous peoples, contributed to this burgeoning interest. Perhaps the wisdom of such people was disregarded for many, many years partly because of the early missionary zeal of clerics encountering “heathenish” peoples in new worlds during the age of exploration on the one hand, and partly due to the totalizing influence of modern science, which has difficulty at times admitting other paradigms for uncovering useful knowledge. At any rate, curanderismo finally seems to be getting a serious hearing.

Among the rumors I heard about fascinating practices under various guises of New World folk healing, one of the most interesting to me was that about the turn-of-the-century curandero and folk saint El Niño Fidencio, a very highly venerated non-canonical saint (i.e., he was elevated, while still living, to the status of folk saint by common consensus of his followers, rather than canonized by church decree). El Niño, as he was called, had lived and practiced and died in the tiny village of Espinazo, Nuevo León, Mexico. El Niño, the stories have it, was a very powerful curandero who had begun as a house-servant for a German doctor for whom he had ended up apprenticing. Through this training, El Niño learned to cross traditional faith-healing with surgical techniques. Part of his appeal in his lifetime—and his enduring pull long after his passing, in 1939 at the youthful age of forty—was his playful, childlike temperament; hence his nickname, El Niño, which means “the child.”

Over the years, I grew more and more curious to see the village of Espinazo and to experience the twice-yearly fiestas held in El Niño’s name. When I finally got an opportunity to go to this village, during the early 1980s, little did I realize that what awaited me was nothing less than my own spiritual awakening.3

What happened to me was nothing less than my transformation from an academic with some personal interest in the folk healing that I saw around me when I was a child, to a man who embraced curanderismo as part of a great tradition and as part of his own identity. In other words, I began then to think of myself not just as a recorder of the arcana of curanderismo; I began to become a curandero myself.

We set out—I went with some American friends of mine; all of us were accustomed to traveling with Samsonite suitcases in comfortable automobiles and airplanes—and in my Lincoln Towncar we crossed at Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. At the Garita, the Customs in Mexico, we learned that we would need to hand over a $500 deposit simply to ensure our return, and also to purchase a special kind of auto insurance in order for us to drive through Mexico.

The wait was so long, and the process of getting through all the red tape so complicated, that ultimately we decided to leave the car behind at the border and take the bus to Espinazo. Naturally, this was much more easily said than done.

We traveled all night to Monterrey, the third largest city in Mexico, in the northern state of Nuevo León. When we arrived, we learned there was no bus from Monterrey to Espinazo. This was a setback, of course, since we knew of no other way to get to our destination. So there we were, stuck in a strange city of two million people, trying to figure out how to get a ride to Espinazo, which is, it turns out, a dusty little stop off the road between Monterrey and the next big city up the highway, Saltillo. Most of the people we encountered in Monterrey had never even heard of Espinazo, which might convey just how insignificant the little town seemed even to people living in a nearby metropolis. So we set out to find a hotel. In the process, I decided to ask an elderly man I encountered where Espinazo was and how to get there, and he informed me that indeed there was a bus to Espinazo. Not only that, it was just around the corner, in a dusty alleyway, and it was about to leave in a few minutes! So my friends and I gathered our suitcases and headed for the alley, where we discovered a rickety old 1940s-era bus loaded not only with human passengers, all of whom looked as if they were very poor, but also with chickens, roosters, goats, and pigs. Only later did the oddness of it all come home to me—this seemed like something straight from a children’s fantasy story, where the way into an alternate, magical world turns out to be just around a nondescript-looking corner, or tucked away inside of someone’s closet. The fare to travel from Monterrey to Espinazo was about $1.00—an unimaginably cheap fare for Americans traveling 30 miles, but probably a considerable enough sum for the other passengers on the bus.

As we drove along the dusty road to Espinazo, we were laughing because half the other passengers were farm animals. There we were—several rather comfortable middle-class people from America, the women carrying Samsonite suitcases—and meanwhile there were pigs running up and down the aisles. As we realized later, people were literally bringing along their food for the festival, in the most effective portable form—still living!

While we were on the bus we met another American citizen, a woman who was, like us, of Mexican heritage; but this particular person had been on the pilgrimage several times before. After we had told her the tale of our difficulties in getting across the border and then in finding the bus to Espinazo, she told us that it was not unusual at all for first-time peregrinos, or pilgrims to Espinazo, to experience some sort of suffering on the journey to Espinazo. She told us that it was in fact very common for first-timers to undergo some kind of a test imposed not by a conscious, active agent (that we know of!) but by circumstances, by inexperience, by fear of the unknown, or other happenstances. (I later heard it speculated that the spirit of El Niño himself imposes this test—to see if pilgrims to his shrine are worthy, or to help them to grow to the kind of spiritual stature they need to possess in order to be worthy.)

We were continually reminded, as we traveled toward the dusty little town, of just how different we really were from the people with whom we were sojourning. As U.S. citizens of Mexican heritage, we had always thought of ourselves as belonging to a distinct minority of a sometimes oppressed people in America, but down here it was plain we were just gringos to the locals, in spite of our physical resemblance to many of them. There we were with our suitcases and hairdryers, and we were surrounded by humble, sincere, poor people; to them we must have appeared exotic creatures, wealthy beyond imagining, living unimaginable lives. We might as well have been from Mars.

And yet these people treated us with sincerity and dignity, and my respect for them, which was already high, only increased. I felt humbled to be in their presence. It was hard not to look into their eyes and feel as if they had experienced life in ways that many of us can only dream about. Perhaps that is only an Americano conceit of mine. But the further I went into this journey of awakening, the more I felt this way.

Our third ordeal was being completely lost once we got to the village. The big feast-day goes on 24 hours a day; there are literally thousands of materias there, people who are folk-healers, like curanderos, wearing colorful tunics and dresses, many of whom are channeling spirits such as those of Aurorita, Don Pedrito Jaramillo, and El Niño Fidencio, all famous folk saints (as opposed to canonized saints). As we got off the bus in Espinazo, and saw this riot of color and lights, and heard the sounds of music coming from different places around the little town, we realized that we had no idea what to do now that we had arrived.

One of the reasons I had come to Espinazo was to meet my friend Chenchito, a man whose reputation as a healer had spread all the way up into Texas. I had met Chenchito (a.k.a. Cresencio Alvarado) through a university colleague of mine, Leo Carrillo, in the office of International Programs at his school near where I worked at the time. Leo was a close friend of Chenchito, and he had suggested I come down to this village to experience the fiesta for myself. Chenchito’s and Leo’s faces were in my mind’s eye as I stood helplessly with my friends on that dusty little road in the middle of a strange town in a foreign land. I began to wonder whether coming had been a mistake; after all we had already been through, we had no idea where to go, or what to do next.

But then, swimming up out of the confusion and exhaustion we all felt, there, miraculously, was Leo Carrillo, standing across the street, waving to us! At this point I hoped that El Niño’s tests of our faith and will to reach Espinazo and figure out what to do once we were there were over. Later on I also ran into another colleague from another university in South Texas, Tony Zavaleta, who, along with a number of American students, was visiting other materias who were friends of Chenchito. So the chances are we wouldn’t have been lost for long.

Just to give you an idea of what the atmosphere was like, there were 20,000 to 30,000 people at the feast. But there were no motels, no life conveniences of the kind to which we are accustomed. Leo told us he was staying in someone’s house, along with his students from the university. This house had a concrete porch in the back, and an outhouse and shower that had been constructed by the students. Chenchito, Leo told us, lived two blocks from the house where he was staying.

So we walked up the street to go meet Chenchito. Let me tell you a bit about him: Chenchito was at this time a man in his sixties, perhaps all of 4 feet-eleven inches tall, but with an outsized smile, full of life, very charismatic. You know he’s around when he walks into a room: he has a childlike personality, full of innocence and play. Judging by the descriptions I have read of El Niño, Chenchito greatly resembles this folk saint in temperament; he has the happiness and innocence that many of us have lost in growing up.

It was 2 A.M. by the time we arrived at Chenchito’s house—we had been traveling all day and a good part of the night to reach Espinazo—but there were 20–30 people there, and more people in the breezeways between the house and the kitchen. Everybody who was there was staying there at Chenchito’s invitation, and by custom everybody who stayed donated food and time for cleaning and cooking, although no money whatsoever was exchanged for either the accommodations or the work. Chenchito had arrived three days earlier by bus with a goat that he had been raising especially for this occasion, when he knew he would have many visitors. When we arrived, Chenchito was in the midst of making cabrito (goat-stew).

Those of us who had arrived that night by bus were treated as special guests from the moment we arrived—in spite of the fact that we, like everyone else, slept on the floor of Chenchito’s house. I have to admit, I never slept so well in my life—in spite of the hard floor, and the close proximity of so many other people in that small space.

The next morning we were awakened by the sound of music—traditional Mexican folk music. After we had cleaned ourselves up as well as we could, we started the ritual traditional for newcomers—that is, we walked to the California pirulito tree (a kind of willow) that El Niño himself had sat under while he was performing his healings. When we arrived at the tree, we circled it three times, and joined a bigger group led by materias, that is, fidencistas (followers of El Niño) clothed in white cotton, with red capes and red hats and red neckerchiefs. Some others wore turquoise-colored hats, capes, and neckerchiefs; apparently these color differences signified the diversity of misiones or groups of followers from throughout Mexico as well as the United States. Some people present at the pirulito tree carried banners showing affiliations with certain other saints and important religious figures, such as Our Lady of Guadalupe, and there were many accordionists...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dedications

- Introduction The Healing Tradition of a Family and a Culture

- Chapter 1 The Awakening

- Chapter 2 I Am Healed by Doña María

- Chapter 3 I Face the Great Black Dog and Other Tales of Magical Cures

- Chapter 4 My Father’s Ancestral Wisdom

- Chapter 5 Exotic Rituals I Have Known

- Chapter 6 I.Q. Tells the Story of Don Pedrito, Curandero

- Chapter 7 The Great Materia, Chenchito Alvarado

- Chapter 8 The Midwife Doña Juana, a Partera

- Chapter 9 Art Esquibel Tells Me the Story of Teresita, Saint of Cabora

- Chapter 10 How I Was Fed and Healed by Plants

- Chapter 11 Folk Healing in This Modern World

- Chapter 12 Curanderismo Goes to School

- Chapter 13 Recent Curanderos

- Epilogue

- Selective Bibliography and Further Reading

- About the Authors

- Index