This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Reining in the Rio Grande

People, Land, and Water

About this book

The Rio Grande was ancient long before the first humans reached its banks. These days, the highly regulated river looks nothing like it did to those early settlers. Alternately viewed as a valuable ecosystem and life-sustaining foundation of community welfare or a commodity to be engineered to yield maximum economic benefit, the Rio Grande has brought many advantages to those who live in its valley, but the benefits have come at a price.

This study examines human interactions with the Rio Grande from prehistoric time to the present day and explores what possibilities remain for the desert river. From the perspectives of law, development, tradition, and geology, the authors weigh what has been gained and lost by reining in the Rio Grande.

This study examines human interactions with the Rio Grande from prehistoric time to the present day and explores what possibilities remain for the desert river. From the perspectives of law, development, tradition, and geology, the authors weigh what has been gained and lost by reining in the Rio Grande.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reining in the Rio Grande by Fred M. Phillips,G. Emlen Hall,Mary E. Black,Black E. Mary in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I

Roots of the Rio Grande in Deep Time

The Rio Grande was already ancient when the first humans reached its banks. Some of its rocks go back to the early stages of the history of Earth, before there were even organisms with hard shells. The course of the river was dictated by the splitting of Earth’s crust in the wake of exceptionally large volcanic eruptions 20 million years ago. The productive aquifers that have sustained middle Rio Grande populations until recent times were deposited as a consequence of global cooling and glaciers in the headwaters during the past 2 million years. Even the course of the river over the last five hundred years has an elaborate history. Looking down on the Rio Grande floodplain from an airplane one sees an intricate braid of loops and whorls—the tracks of a river that was constantly changing its path.

Unquestionably, the Rio Grande has an identity that transcends human concerns. That identity begins with the building blocks of the earth itself—the physical material of which the Rio Grande basin is composed. Those fundamental earth materials have crystallized, eroded, redeposited, deformed, and uplifted over almost unimaginably vast intervals of time in order to produce the landscape and river that we see today. Today’s Rio Grande is consequent on that long primeval history. The time span since the first human set eyes on the Rio Grande is infinitesimal in comparison to that long saga, yet it far exceeds the length of recorded human history.

And yet the basin’s natural geographic features—the shape, contours, and composition of the land and the way its waters flow above and below the earth’s surface—are what first attracted or repelled human settlers, who would in turn transform the river. Where does the rain fall? What direction does the river flow? Does it flow through a fertile plain or a precipitous gorge? What pattern does the groundwater follow as it creeps over millennia toward the river? Can good groundwater be easily sucked from the earth or is it difficult to pump or salty? The geological events of an almost unimaginably distant past provide the answers to all these questions. Geologic processes shaped the groundwater, the rivers and lakes, and the mountains and valleys of the Rio Grande basin. The availability of water is often the most important consideration determining human habitation. Unlike much of the less arid eastern United States, where outside the major urban centers the population is fairly evenly distributed, vast regions of modern New Mexico are almost uninhabited and other areas have narrow corridors of dense populations (see plate 2). In arid regions, people follow the water.

The major focus of this book is on the interaction of human populations with the Rio Grande, from prehistoric time to present day. This chapter departs from that emphasis to look at the geology, hydrology, and biology of the river system—its natural history—to provide a basis for understanding this later interaction.

Deep Time

The ancient Cochiti people felt a deep affinity for the earth upon which they lived, as do their descendants, for they believed that they had emerged into the sunlight of the present world from a sipapu, an opening in the ground. In truth, all people find themselves situated upon a landscape they did not create and that vastly predates them. Although the ancient Pueblo peoples possessed an acute sense of antiquity of the earth, only in the past few hundred years has modern science begun to quantify the lengths of time that have been required to shape the land of the Rio Grande and the river itself.

For most of the history of humankind our perceptions of space and time have been extrapolated from familiar human scales. The stars were not so low that they could be touched by human hand from the top of a high mountain, but perhaps they could be reached by a high-flying eagle. The mountains and hills were not created in our grandparents’ time; perhaps they came into being as long as fifty generations ago. The penetrating eye of modern science has exploded these simple, commonsense scales of reality. The planets are distant from us by many thousands of multiples of the diameter of Earth, and the true stars are vastly more distant than that. Our part of the universe is arranged into a galaxy containing billions of stars, and we can see thousands of galaxies with immense stretches of space between them. The true scale of the universe is so immense that scientists have coined the name deep space to attempt to convey its immensity. The Rio Grande basin is only an infinitesimal part of that deep space, but it is a part.

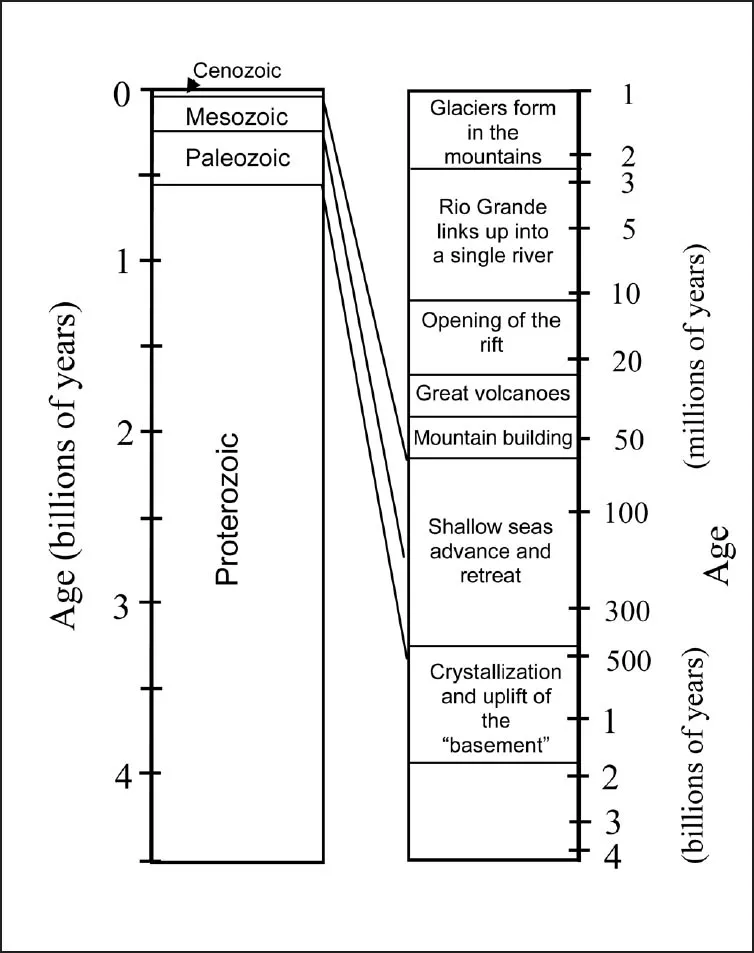

Our perception of time is similarly limited. Fifty generations is actually less than one-half of 1 percent of the time to the origin of our species. The age of our species is less than 1 percent of the time since the extinction of the dinosaurs, but that time is only the last 14 percent of the age of Earth. The term deep time has come to be used to convey the scope of time over which Earth has been shaped. It is into this deep time we delve very briefly to understand the ancestry of the Rio Grande.

An illustration of the length of time involved in the formation of the Rio Grande basin. The time scale on the left is linear. That on the right is expanded toward the present to show the important geological events in the basin.

In the Beginning

Long before there was a Rio Grande, the earth churned and mixed deep below its crust, seas repeatedly flooded the land and retreated, the earth buckled and mountain ranges rose, volcanoes exploded and lava flowed, and the earth again cooled and settled. Over billions of years these forces shaped the land of the present Rio Grande basin. These geologic events determined the way and direction that groundwater flows, its quality, and its abundance. And they laid the path for the Great River to follow.

The age of shallow seas

The first 4 billion years of Earth (the Proterozoic; see plate 3) was a period of long, slow upheaval that carried rock and sediments deep below the earth’s crust where they recrystallized into a hard, dense layer of material such as gneiss and granite.1 Geologists refer to this hard crystalline layer, through which little groundwater can circulate, as the basement. By 450 million years ago, much of what is now New Mexico and Colorado had eroded down to this layer. To put 450 million years in perspective, had humans been alive then, we would be the thirteen-millionth generation of their descendants.

Next began a long period of advance and retreat of seas across the relatively flat land of this region, along with the deposition of sediment that covers much of the hard basement layer.2 Marine animals teemed in the shallow seas and their minute shells rained down on the seabed to form limestone layers where the seas were shallow. Layers of shale were deposited from erosion of the surrounding land when the seas deepened. Layers of fine-grained beach sand were created from wave action as the coastline advanced and retreated.

The last interior seaway retreated north around 90 million years ago, but the sedimentary deposits that were left behind affect groundwater even today. Groundwater flows easily through limestone layers, supplying, for example, the extensive agriculture of the Pecos River valley. Sandy layers left in areas such as northwestern New Mexico similarly allow groundwater to easily flow and so are eagerly sought by well drillers. Shale, in contrast, obstructs the easy passage of groundwater.

In some locations, many different sedimentary layers are stacked one upon the other, creating a complex pattern of flow. In areas such as the high plains of eastern New Mexico and western Texas, extensive farmlands and numerous towns today sit atop permeable rock that contains large stores of fresh water, with the flow pushed by high water pressure. Where the geologic layers contain brackish, salty water that can ultimately be traced back to ancient seas, such as the Tularosa basin in south-central New Mexico, the groundwater flow is limited and slow and the land above is mostly empty desert.

The age of mountain building

One hundred million years ago, the movement of the plates comprising the earth’s crust began to deform the area that would become the Rio Grande. A deep, underflowing layer of the oceanic floor from the Pacific Ocean, which had worked its way beneath North America, dragged against the continent above it, causing the land surface to buckle and rise. The continent thickened and eventually rose far above sea level, where it has remained to the present day.3 Many of the high areas that formed this way now constitute parts of the Rocky Mountains.

The mountains rose well above their surrounding lowlands. Basins sank between the mountain ranges and collected older sediments that eroded from these higher elevations. This evolution of basins and ranges was critical to the formation of the Rio Grande. The high ranges catch the atmospheric moisture that moves east across North America, providing the rain and snow needed to sustain a large river.

The age of supervolcanoes

The next big period of geologic change left its mark on the land in similarly dramatic fashion: through volcanic explosions that left ash and pumice deposits that still affect runoff and streamflow.

What set off these explosions? The long episode of mountain uplift ended around 40 million years ago when the two plates underlying the Pacific Ocean and North America shifted direction and started to slide past each other in a north-south orientation.4 The change in motion sliced off the slab of ocean floor that was being shoved eastward below the continent, causing it to sink into the earth’s mantle, and forced hotter rock up from below, which warmed the continental crust. Rock near the base of the continent melted and rose in the fashion of the colored blobs in a lava lamp. Gases accumulated near the tops of these magma blobs and eventually burst forth. The molten rock expanded as pressure was released. The effect is much like what happens when a bottle of champagne is shaken and the cork popped: a column of froth shoots skyward.

Forty or fifty of these immense pops, sometimes called supervolcanoes,5 devastated the landscape of what is present-day New Mexico and Colorado 37 million to 21 million years ago (see plate 4). The biggest of these produced more than one thousand cubic miles of lava—enough to completely fill Lake Erie—and are among the largest eruptions in the entire history of Earth.6 They left circular holes in the earth as large as fifty miles across.

Thick layers of pumice blanketed the entire landscape, often followed by incandescent clouds of volcanic ash that settled and cooled into hard volcanic rock that transmits water very well. In areas that get less rainfall, such as western New Mexico, streams and rivers are rare, because the precipitation sinks easily into the volcanic rocks and down into the groundwater, instead of running off in surface flows.

The beginning of the big river rift

The pulse of heat produced by the sinking oceanic slab dissipated 25 to 20 million years ago, and volcanic activity waned. This period of calm set the stage for the birth of the Rio Grande. In what is now the Rio Grande basin, the earth’s crust was left vulnerable, made thicker than surrounding areas from the compression of land that formed the basins and mountain ranges and also softer from the subsequent heating. As the volcanoes ceased, the elevated crust divided and very slowly flowed east and west along a north/south fault zone,7 creating a geological rift that began to open and define the boundary of the Rio Grande drainage basin. Were it not for the rift, the streams that originate in the northern mountains would not collect today into a single large river, but would spread out in many directions.

That the Rio Grande follows a remarkably linear north/south course from its headwaters in the San Juan Mountains to El Paso, Texas, is no accident. The river follows the depression left by the opening of the rift. The rate at which the rift opened was greatest 20 to 10 million years ago, but it is still very slowly growing wider. It opened because the land was stretching and extending, its center was subsiding, and the elevated blocks along its margins slumped into the depression. It collapsed in stages, following a complicated geometry, with some areas dropping deeper than others and sections opening at different times, but generally from north to south through time.

The very formation of the rift ensured that it would eventually be filled. The wettest portion of the Rio Grande drainage basin is in the highlands around its headwaters. As the climate became moister due to increasing elevation of the uplifted areas, increasingly vigorous northern streams began to bring abundant coarse sediment into the subsiding streams. This sediment filled the basins faster than they were sinking; consequently, the basins filled to the brim. Streams began to spill from one basin to the next downstream. The rift now became a kind of trough or drain that channeled runoff into a single path. The more water that flowed into the rift, the more sediment the river carried, and the quicker it filled basins downstream. Each basin that was filled ad...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: Cochiti Pueblo and a Changing River

- Chapter I: Roots of the Rio Grande in Deep Time

- Chapter II: Early Cultures

- Chapter III: Newcomers to the Land

- Chapter IV: A New U.S. Regime

- Chapter V: The River Pushes Back

- Chapter VI: Conquest of the River by Science and Law

- Chapter VII: Big Dams, Irrigation Districts, and a Compact

- Chapter VIII: Mount Reynolds on the Middle Rio Grande

- Chapter IX: Shifting Values, New Forces on the Rio Grande

- Chapter X: Fulfilling Rio Grande Demands: What Has to Give?

- Chapter XI: The Future of an Old River

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Color Plates

- Index