eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Volunteering for a Cause

Gender, Faith, and Charity in Mexico from the Reform to the Revolution

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Volunteering for a Cause

Gender, Faith, and Charity in Mexico from the Reform to the Revolution

About this book

This thoughtful study challenges a number of widespread assumptions about the role of Catholicism in Mexican history by examining two related Catholic charities: the male Society of St. Vincent de Paul and the Ladies of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. With thousands of volunteers, these lay groups not only survived the liberal reforms of the mid-nineteenth century but thrived, offering educational, medical, and other services to hundreds of thousands of poor people.

Arrom stresses the prominence of women among the volunteers, showing the many ways that Catholicism promoted Mexican modernization rather than being an obstacle to it. Moreover, by reinserting religion into public life, these organizations defied the secularizing policies of the Mexican government. By comparing the male and female organizations collectively, the work shows that the relationship between gender, faith, and charity was much more complicated than is usually believed, with devout men and women supporting the Catholic project in complementary ways.

Arrom stresses the prominence of women among the volunteers, showing the many ways that Catholicism promoted Mexican modernization rather than being an obstacle to it. Moreover, by reinserting religion into public life, these organizations defied the secularizing policies of the Mexican government. By comparing the male and female organizations collectively, the work shows that the relationship between gender, faith, and charity was much more complicated than is usually believed, with devout men and women supporting the Catholic project in complementary ways.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Volunteering for a Cause by Silvia Marina Arrom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Mexican History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

The First Decade

Preparing the Ground for Social Catholicism

THE SECOND VATICAN Council (1962–1965) that ushered in liberation theology is rightly considered a major turning point in Catholic history. In recent years, however, scholars have begun to identify its significant continuities with earlier progressive movements, particularly with those that emerged after Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum encyclical of 1891.1 In Mexico, Social Catholicism was flourishing by the turn of the twentieth century. Catholic trade unions and other workers’ organizations proliferated, national congresses regularly brought together Catholics who sought solutions to the Social Question, and in 1911 a Catholic political party was created to pursue a Social Catholic agenda. Indeed, on the eve of the revolution, Mexico had what was arguably the strongest Social Catholic movement in Latin America.

Yet its roots in Mexico are much older than usually assumed, the culmination of a long process of building Catholic structures that is sometimes termed the Catholic Restoration. Until recently, few scholars were aware that a religious revival occurred after the supposedly definitive defeat of the church during the Reforma. Those who recognized its existence usually followed Father Mariano Cuevas in dating its beginning to 1876, when Porfirio Díaz came to power and proceeded to mend fences with the church.2 A few scholars pushed the date back to 1867, immediately after the fall of the Second Empire brought the church to its knees.3 There are several hints that it may have begun much earlier, however. Margaret Chowning identified three new pious associations founded in Michoacán in the 1840s, and David Gilbert posited that “the Mexican church was actually in a period of dynamic growth and renewal when the Liberal assault began.”4 He attributed the Catholic resurgence not only to the confirmation of the first republican bishops in 1831 and the resolution in 1851 of the dispute between the church and state over the right to appoint clerics (the patronato) but also to the increased fervor and activism of the Catholic laity who were inspired by the religious revival occurring throughout Europe.

The history of the Vincentian conferences in Mexico shows that this process was already underway in 1844 when the French lay movement reached Mexico City. Indeed, the founding members of the Sociedad de San Vicente de Paul were at the center of an effort to strengthen Catholicism while simultaneously working to improve public health, poor relief, and elementary education. The conferences were only one part of their multipronged strategy, which included founding two new religious orders and combating the spread of anticlerical ideals through a vibrant Catholic press.

The Vincentian lay movement had a strong social component from the outset. Half a century before Rerum Novarum, the Mexican volunteers were the Latin American pioneers of a new kind of lay activism with a social conscience that saw service to the poor and helpless as a form of manifesting their devotion. Although the Sociedad de San Vicente de Paul got off to a slow start, by the end of the first decade it had planted the seeds of a dynamic charitable initiative that would survive the onslaught of the Liberal Reforma and blossom during the Porfiriato. One of many Catholic organizations that contributed to the religious revival of the late nineteenth century, it stood out because of its early use of social programs to reinvigorate the faith. By mobilizing committed Catholics to work for the common good, building lay institutions dedicated to serving the needy, and expanding the influence of the church, it helped prepare the ground for the Social Catholicism of the 1890s.

The Foundational Story

The few available chronicles of the Mexican Society of Saint Vincent de Paul overlook these aspects of the lay movement because their authors had a very different set of concerns.5 Written by Vincentian priests or society officers to commemorate the 50th anniversary in 1895, 100th anniversary in 1945, and impending 150th anniversary in 1995, these short “in-house” histories glorify the organization and highlight the role of its founders. By starting their stories in France, they privilege the French context. In addition, they minimize the differences between the Mexican and French branches of the organization and gloss over the problems of the first decade.

The chronicles written by priests usually begin in the seventeenth century with Father Vincent de Paul (1581–1660), creator of three of the four organizations that comprised the Vincentian family. His first foundation, in 1617, was the organization of laywomen known as the Dames de la Charité. He then founded two religious orders in quick succession, the male Congrégation de la Mission in 1625 and the female Filles de la Charité in 1634. For his patronage of charitable works he was canonized in 1737. Focusing on the role of Saint Vincent, these histories emphasize the timelessness of Vincentian charity and neglect its eighteenth-century decline and nineteenth-century renewal and transformation.

When in 1945 Father Ramiro Camacho wrote the centennial history of the Vincentian organizations in Mexico, he instead chose to open his story in Paris in 1793. His tale began with the “delirium of nightmares enveloping that period of the French Revolution known as The Terror.” The first page recounted the “horrible” nights of July 12 and13, when a crazed mob sacked the Lazarist Convent, headquarters of the Vincentian organizations, chopped the head off a statue of Saint Vincent de Paul, and paraded it on a pike through the streets of Paris. The second page bemoaned the woes that followed: the confiscation of ecclesiastical property, the assassination of Paulist priests, and the near death of Saint Vincent’s “marvelous” works of “charity, drowning in a pool of blood.” For Father Camacho, the persecution and survival of the French church was the logical starting point because it mirrored the experience he had just lived through in Mexico: attacks on the church at the hands of revolutionary caudillos, especially after 1913, and an all-out war between the church and revolutionary state from 1926 to 1929 that poisoned church-state relations until 1940, when the new president, Ávila Camacho, signaled the end of the conflict with the simple declaration “Soy creyente; I am a believer.”

Earlier histories did not set their narratives in the context of defending the church from hostile forces because the situation when the conferences reached Mexico was far less embattled. Most chronicles simply begin in Paris with the birth of the men’s organization in 1833. On April 23 the twenty-year-old university student Frédéric Ozanam (1813–1853), along with several other youths under the guidance of Catholic journalist Emmanuel Bailly, founded the Conférence de la Charité as a way to combat the decline of Catholicism in postrevolutionary France. As they looked at the society around them, Ozanam and his fellow students identified a host of problems—from immorality, materialism, individualism, and alienation to class conflict—that they blamed on the separation of the church from public life and the subsequent loss of faith. They were also deeply troubled by the growing poverty that accompanied nineteenth-century industrialization and urbanization. The solutions proposed by utopian socialists like Saint-Simon further threatened the centrality of religion. The pious young men therefore resolved to use Christian charity to defend Catholicism while addressing the needs of the urban poor. Their method was to meet weekly in their small groups, pray together to strengthen their own devotion, and then go to the abodes of ailing paupers, taking them corporal as well as spiritual aid. The volunteers hoped that establishing direct, face-to-face connections with the needy would help restore social harmony while simultaneously working to achieve the salvation of both the clients and the volunteers. Although the home visits would remain the principal activity of the conferences, they quickly took on additional projects that went beyond simple charity, such as distributing religious texts, providing children with a Christian formation, “patronizing” apprentices by giving them both a practical and religious education, and establishing night schools, mutual savings funds, and job placement services for the unemployed.6

The first conference founded in 1833 was the germ of the lay movement that would become the international Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul. This fourth member of the Vincentian family differed from the other three in that, rather than being directed by Paulist priests, it was nominally independent from the church and run exclusively by its lay leaders. It was a sign of the lay activism that would characterize the nineteenth century as the spread of liberalism created a more self-consciously Catholic laity eager to champion their religion as well as to help solve the social problems of their communities. The new model of militant Catholicism found many adherents throughout the world where the church was under attack and poverty was deepening.

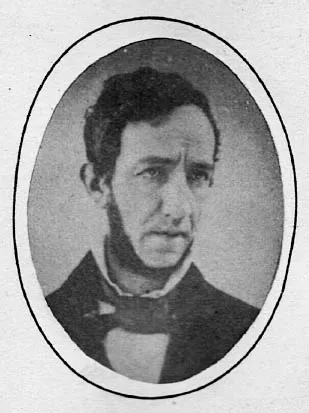

Even when the foundational narratives moved to Mexico in 1844, they emphasized the French connection. Dr. Manuel Andrade y Pastor (1809–1848) had witnessed the birth of the men’s conferences while studying medicine in Paris from May 1833 to June 1836 (fig. 1.1). After returning to his homeland, he worked tirelessly to establish branches of the four Vincentian organizations in Mexico. His efforts began to bear fruit in 1844, when the first Sisters of Charity arrived and the first male chapter met. The next year the Sociedad de San Vicente de Paul was formally aggregated by the French association, making 1845 the founding date later recognized by the Mexican society. The Paulist priests also received permission to operate in Mexico in 1845, and a few years later they proceeded to found the Ladies of Charity’s conferences.

There could be other ways of telling the story. For example, instead of focusing exclusively on the three male protagonists (Saint Vincent, Ozanam, and Andrade), one could highlight the role of women in creating these organizations. In France it was apparently Marguerite de Silly and Geneviève Fayet who encouraged Father Vincent de Paul to found the Dames de la Charité in the first place,7 and it was Sister Rosalie Rendu (a Fille de la Charité) who gave Ozanam the idea of creating laymens’ conferences modeled on the centuries-old women’s organization; indeed, according to her nineteenth-century biographer, she was the “soul” of the male conferences.8 The initiative for refounding the Dames de la Charité in 1840 also came from a laywoman, the Vicomtesse Le Vavasseur.9 In Mexico the ex-condesa Ana Gómez de la Cortina, who funded the establishment of the Sisters of Charity and then took the habit herself, deserves to share the credit with Andrade for that foundation.10 Reinserting female agency helps explain why the Mexican conferences would so quickly become feminized in the 1860s. A close look at the society’s early history shows that the male volunteers were in fact collaborating with women from the start.

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Dr. Manuel Andrade y Pastor (1809–1848), founder of the Mexican Society of Saint Vincent de Paul. From collection of the Sociedad San Vicente de Paul de México.

An alternative narrative would also emphasize the distinctiveness of the Mexican society. Its early foundation date put Mexico at the forefront of the Vincentian lay movement and helps explain some of the differences between the Mexican and French branches. The first conference in Mexico City was established on December 15, 1844—only twelve years after the Parisian Conférence de la Charité. The Mexican sociedad was thus born before the French société was fully institutionalized. It preceded its official recognition by the Vatican, which came in two papal briefs of January 10 and August 12, 1845, that granted indulgences to its volunteers and benefactors; and it preceded the publication in 1847 of an instruction manual for forming new conferences.11 Although the organization would eventually expand to cover the entire world, in 1845 it had barely spread beyond French borders. Mexico was the sixth country where it took root after Belgium, England, Ireland, Italy, and Scotland, and it was home to the first branch in the Americas, closely followed by the United States and Canada.12 The other Latin American associations came later, beginning with Puerto Rico in 1853.13

The singularity of the Mexican society also reflects its adaptation to local needs and conditions. Unlike many foreign branches of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul founded by missionary priests intent on exporting Catholic organizations from France, Mexico’s conferences came as a result of local lay initiative. Given Dr. Andrade’s active role in promoting it, Mexico’s cannot be considered an external imposition. Yet his efforts to establish the Vincentian organizations did not only stem from similarities between...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The First Decade Preparing the Ground for Social Catholicism

- 2. The Male Volunteers Face the Liberal Reforma

- 3. The Mobilization of Women

- 4. The Gendering of Vincentian Charity

- 5. Jalisco A Case Study of Militant Catholicism

- 6. Charity for the Modern World Concluding Remarks

- Epilogue What My Grandmothers Taught Me

- Appendix 1. Society of Saint Vincent de Paul Superior Council Officers, 1845–1910

- Appendix 2. Ladies of Charity Superior Council Officers, 1863–1911

- Appendix 3. Guadalajara Society Central Council Officers, 1852–1909

- Appendix 4. Guadalajara Archdiocese Ladies of Charity Central Council Officers, 1864–1913

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index