This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

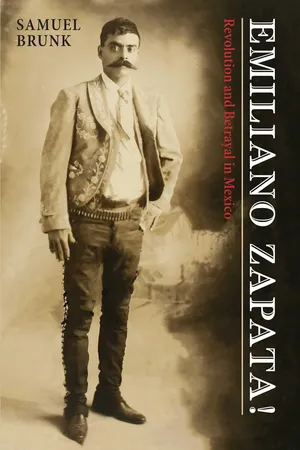

The life of Mexican Revolutionary Emiliano Zapata was the stuff that legends are made of. Born and raised in a tiny village in the small south-central state of Morelos, he led an uprising in 1911--one strand of the larger Mexican Revolution--against the regime of long-time president Porfirio Díaz. He fought not to fulfill personal ambitions, but for the campesinos of Morelos, whose rights were being systematically ignored in Don Porfirio's courts.

Expanding haciendas had been appropriating land and water for centuries in the state, but as the twentieth century began things were becoming desperate. It was not long before Díaz fell. But Zapata then discovered that other national leaders--Francisco Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Venustiano Carranza--would not put things right, and so he fought them too. He fought for nearly a decade until, in 1919, he was gunned down in an ambush at the hacienda Chinameca.

In this new political biography of Zapata, Brunk, noted journalist and scholar, shows us Zapata the leader as opposed to Zapata the archetypal peasant revolutionary. In previous writings on Zapata, the movement is covered and Zapata the man gets lost in the shuffle. Brunk clearly demonstrates that Zapata's choices and actions did indeed have an historical impact.

Expanding haciendas had been appropriating land and water for centuries in the state, but as the twentieth century began things were becoming desperate. It was not long before Díaz fell. But Zapata then discovered that other national leaders--Francisco Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Venustiano Carranza--would not put things right, and so he fought them too. He fought for nearly a decade until, in 1919, he was gunned down in an ambush at the hacienda Chinameca.

In this new political biography of Zapata, Brunk, noted journalist and scholar, shows us Zapata the leader as opposed to Zapata the archetypal peasant revolutionary. In previous writings on Zapata, the movement is covered and Zapata the man gets lost in the shuffle. Brunk clearly demonstrates that Zapata's choices and actions did indeed have an historical impact.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Emiliano Zapata! by Samuel Brunk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1The Making of a Rebel

Five months earlier, in July, the dictator Victoriano Huerta had finally surrendered power and gone into exile, but the fighting continued against the government he left behind. It meant a lot of time on horseback. On July 19 Zapata took Topilejo, the next day Milpa Alta, and then San Pablo Actopan, chasing off small bands of federal troops. There was nothing the matter with time on horseback; one found a certain peace there, or found peace at least after dark, sleeping anonymously on the fringes of a mountain camp. The trouble lay more in a kind of frustration. In these villages of the Federal District, only a few miles south of the center of Mexico City, national power flitted just beyond Zapata’s reach. Home, however, was close too, just over the mountains to the south, and the voices of home never stopped calling. Remigio Cortés made him the gift of a machete; Onecima Promera asked for money from her death bed; and at the end of the month birthday wishes began to find him, along with news from Yautepec about a child of his that nearly died.2

Pursuing that elusive national power that might guarantee the change he sought for Mexico, in July and August Zapata had had several discussions with representatives of the other factions that had fought Huerta. If the fighting was bad, the talking generally felt worse. Dr. Atl, Antenor Sala, Manuel N. Robles, Guillermo García Aragón, Carmen Serdán, Lucio Blanco, Juan Sarabia, Antonio I. Villarreal, Luis Cabrera—the list of messengers, sycophants, profiteers could go on and on. Zapata tried to make it clear that peace was impossible unless everyone signed the Plan of Ayala, but it was sometimes hard to know if it was that simple, and Zapata got angry and perhaps even a little ill. By the end of August he had heard enough, at least, to make up his mind about the hacendado Venustiano Carranza, leader of the northern, Constitutionalist faction. Carranza was a man who could not be trusted; he was only in the revolution for himself.3

In September and October things had settled down a little. Carranza’s emissaries stopped coming, and with the bloody fall of Cuernavaca in mid-August Zapata controlled all of Morelos. He could then respond to requests for money from his cousin Alberta Merino, and from his compadre Lucio Rios in Cuautla, who wanted fifty pesos to start a small business. Emigdio Alcalco had again raised the matter of a baptism at Tepalcingo, and Zapata had even found time to attend a saint’s day celebration or two. Of course, there was no relaxing. Carranza had negotiated his way into Mexico City, bringing his forces face to face, in a precarious cease-fire, with those of Zapata in the southern Federal District.4 Plus there was the question of a second prominent northern revolutionary—Francisco “Pancho” Villa—who had also come to hate Carranza and sought Zapata’s support against him.

Sometime in October or November Zapata had decided to give Villa that support, and the war started again. On the night of November 24 Zapata’s men penetrated to the center of Mexico City: a share of national power was finally theirs. Then, on December 4, Zapata and Villa had met for the first time at Xochimilco in the Federal District. Like Zapata, Villa was a man of the people, but there the resemblance ended. A large, animated man, dressed in khaki, Villa was not exactly what Zapata had expected. Zapata quickly discovered, in fact, that his new ally did not even drink. Still the meeting went smoothly enough. Villa agreed to recognize the land reform goals of the Plan of Ayala and to send Zapata much needed arms and ammunition. And so on December 6, apparently of one mind and with their combined forces behind them, they rode into Mexico City together to the cheers of a wildly enthusiastic crowd.5

Zapata got through it all because there was so much at stake, but it had not been his kind of celebration. He hated Mexico City, both for what it was and what it stood for. On the ninth of December he gladly left to plan the attack on Puebla; on the sixteenth Puebla fell. Carranza was on the run, and it seemed that this round of fighting would soon be over. But there were difficulties. Zapata’s intellectual advisors were already bickering with those of Villa and other nominal allies; nearly every night in the capital scores were being settled by assassination; and the discipline of many of Zapata’s men was no match for the temptations of Mexico City. Ambitions and expectations were everywhere on the increase, and they raised doubts in Zapata’s mind. Indeed, it was impossible to know who could be trusted. Surely the people of Mexico City would have cheered as loudly for anyone else who was winning; and why had Villa been so slow to send Zapata the artillery pieces he needed for the Puebla siege? There was no peace in this; there was no feeling in the victory in Mexico City or in Puebla, no remembering what the years of struggle and bloodshed had all been for, no knowing what, if anything, had been won.6

And so Zapata left the front at Puebla just before Christmas in 1914. As he crossed into Morelos the voices grew louder. The voices of the people who fought for him and the people he fought for, voices from the green valleys and dry hills of another Morelos winter. First down to Tlaltizapán, his new headquarters; then up into the mountains, to Quilamula. There, when he got up on a cloudless morning, he might put a chair outside under the fruit trees and sit among the chickens pecking through the dust, smell the horses, smoke a cigar. And when the birds stopped screeching long enough, he might hear the pat pat pat of palm against corn meal as Gregoria made the tortillas.7 It would take only a few minutes of peace to remember the point and feel what was won, and when the cigar was finished he would try, as he always did, to find a way to answer the voices.

Zapata was born on August 8, 1879, in a two-room house of adobe walls and thatch roof in the village of Anenecuilco, Morelos. The ninth of ten children of Gabriel Zapata and Cleofas Salazar—both mestizos of campesino background—he was among only four or five who survived their childhood. The Zapatas worked a plot of village land, and owned some cattle and horses in which they traded. Gabriel also had ties to the nearby hacienda Hospital, from which he probably rented land upon occasion, and where he may have worked at times in a supervisory role. In relative terms, they were not especially poor: though luxuries and comforts were few, when it came to necessities—the tortillas, beans, and chile of everyday life—they did better than most of their neighbors.8

Although rural Mexican society did not put a premium on education, Zapata’s father sent him to school at about age seven, “to get him out of the sun, and so he can learn a little.” Classes were probably conducted at Villa de Ayala—the head village of the municipality of which Anenecuilco was a part—and attended by perhaps twenty-five children of various ages. Because work was the top priority, Zapata’s schooling was irregular, but he did learn to read and write and may have developed an interest in Mexican history as well. The product of a haphazard country system with limited goals, his would have been considered a sufficient formal education by most of the villagers of Morelos.9

Zapata was probably not sorry to leave his school days behind, for the place where he grew up had many other attractions. Laced with irrigation canals and rock walls, Anenecuilco was a scattering of low-slung adobe houses much like his own. It was always warm there and often hot. In the winter, when it did not rain, the sky was a deep blue above the dry, stony hills that rose to the west of the village, and the valley glowed green with sugarcane. When the rains came in the summer the small homes of Anenecuilco nearly disappeared in a sea of foliage and flowers and fruit; and corn and other foodstuffs grew in the hills where irrigation did not reach. Zapata enjoyed the work of a campesino, especially when it involved animals. Though most of Anenecuilco’s land was owned communally, each family farmed its own plot. The Zapatas hired extra labor when it was needed, but hiring labor was expensive. And so like other local boys Zapata began—by the age of eight or nine—to contribute to the family economy by hauling wood and fodder and helping with the livestock and planting. His life was increasingly dictated by the rhythms of sunup and sundown, of planting and harvest: preparing the ground in May, sowing the corn in June, three major weedings, and in November or December bringing in the crops. Zapata also helped an aunt who lived next door with her chores, and later cared for the cattle of a local Spaniard. Over time he accumulated animals of his own, often as a reward for his work: his father gave him a mule when he began school, and then a horse named “La Papaya”; and other relatives and employers made him similar gifts.10

Zapata was an energetic and perhaps a somewhat nervous child. One cousin tells of the time he mounted his Aunt Crispina’s horse bareback and shot off through the underbrush at breakneck speed. When he returned tousled and torn a few minutes later, he merely bragged about having managed to hang on, as if oblivious to the danger he had put himself through. Of course, this riding ability was not innate; it was part of the informal education of the place. Gabriel Zapata was himself a good horseman, and he had Emiliano practicing jumps by the age of twelve. Because Gabriel knew the value of horsemanship on the local scene, the younger Zapata was not offered sympathy when he fell, but rather a scolding for his clumsiness. This harsh training, so the story goes, only inspired Emiliano. Accepting the challenge, he soon perfected his jumps over a nearby stone wall, and was then taken out to the main street to demonstrate his talent in public.11

Another important skill for a local boy—the use of firearms—was taught him by his uncle José Zapata on their deer hunting expeditions together. From the same uncle and from another named Cristino he heard stories to go with such lessons, and to flesh out his more formal instruction in history. Some of these stories concerned the exploits of his uncles on behalf of the Liberals during the battles of the Reform era, battles that helped form the Mexican nation. Others dealt with the forays of a group of outlaws called the Plateados. Led by a man named Salomé Plasencia who epitomized charro elegance—embroidered shirts of Brittany cloth, wide sombreros, splendid horses—these men raided haciendas and assaulted travellers in Morelos during the 1860s. But they failed to give their rebellion meaning to match its style, and so Cristino and other villagers fought them, and saw Plasencia hang.12

Other stories still worth telling came from a time that Cristino and José could not remember. Locals also helped make history during the War of Independence, when in the larger town of Cuautla, a few miles to Anenecuilco’s north, rebel José María Morelos y Pavón was besieged for nearly three months in 1812 by troops loyal to the Viceroy. Many Morelenses fought on the side of the rebels. The most renowned of them was hacendado Francisco Ayala, who was married to a Zapata from Anenecuilco. It was he who gave his name to Villa de Ayala, as Morelos y Pavón eventually gave his own to the state. Zapata’s maternal grandfather played a smaller part during the siege. Just a young boy at the time, he smuggled supplies past royalist lines.13

Thus had Zapatas and Anenecuilcans provided sure evidence that they were not averse to standing up for what they believed in. They had fought for Independence and for the Liberal Constitution of 1857. They had fought against the 1860s intervention of the French, and against the clericalism and militarism of the Conservative party. In the process they had helped create and protect a national government. And though what was at stake for the villagers of Morelos in the national politics of the nineteenth century was problematic enough that local campesinos could usually be found on both sides in any confrontation, they had demonstrated what kind of national government most of them wanted by consistently supporting politicians who favored a decentralized state that would largely allow them to govern themselves. In fact, the entire Cuautla region had become a bastion of Liberal and federalist feeling.

The campesinos of Zapata’s world understood themselves, in other words, to be part of the Mexican nation—Anenecuilco was, after all, little more than fifty miles south of Mexico City. Still their immediate concerns were local, and as they always do for peasants, those immediate concerns centered around land. They liked politicians who promised to let them run things for themselves, but they also listened for another kind of appeal. Zapata’s grandfather may have thought he heard it in the nebulous agrarianism of Morelos y Pavón. Later, during the 1870s, yet another Zapata certainly heard it during his personal conversations with a Liberal named Porfirio Díaz, who sought to gain the presidency through rebellion, and eventually did so. Anenecuilcans listened for any indication that a politician might demand that the land and water the haciendas of Morelos had stolen from the villages over the years be returned to their rightful owners. They listened, and they hoped, but they were always disappointed.14

Because land was so central to life in Anenecuilco, Zapata undoubtedly heard stories, as he grew, about the struggle against the haciendas. Morelos began to receive its modern form when the Spanish entered the area in 1521. Like many other settlements still around in 1900, Anenecuilco already existed when the Spanish arrived. But when they discovered that the lowlands of the region were wonderfully suited for growing sugar, the conquerors began to threaten the Indian villages by competing with them for resources. To produce sugar the new arrivals needed land and water, commodities that became increasingly available during the sixteenth century, as European diseases decimated the native population. The Spanish also needed labor, which they were able to secure through a variety of legal and economic coercions despite the demographic collapse. Near the end of the sixteenth century sugar boomed. Haciendas sprouted all around Cuautla just as the decline in Indian population began to slow. Pressure on communal resources grew. In fact, the very existence of Anenecuilco was already endangered in 1603, when the colonial government suggested that its shrinking population be combined with that of Cuautla.15

Meaning in Nahuatl “the place where the water rushes,” Anenecuilco—land, water, and culture—seemed to its inhabitants worth fighting for. The result was what one observer called a “long continuous movement of resistance.” In 1603 that resistance was successful, but in the long run it faced difficult odds. After a late seventeenth-century sugar recession decreased conflict for a time, the latter half of the eighteenth century brought better economic conditions for the industry, and the haciendas again used force and guile to push onto village holdings. No longer economically viable, many communities disappeared. While some legal recourse did remain, laws emanating from the sixteenth century that were designed to protect the Indians rarely worked as they were meant to, and legal procedures did little to stop the greedy hacendados. In the villages there was a growing malaise—some e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Coyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Making of a Rebel

- 2 The Hacendado’s Revolution

- 3 The Birth of Zapatismo

- 4 Victory, In Part

- 5 The National Challenge

- 6 A Political Whirlwind

- 7 Decline and Betrayal

- 8 The Road to Chinameca

- 9 Epilogue and Conclusion

- Notes

- Sources

- Index