eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

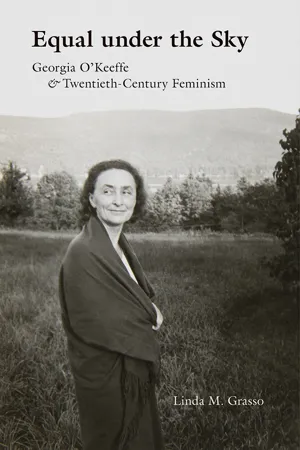

Equal under the Sky

Georgia O'Keeffe and Twentieth-Century Feminism

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Equal under the Sky is the first historical study of Georgia O’Keeffe’s complex involvement with, and influence on, US feminism from the 1910s to the 1970s. Utilizing understudied sources such as fan letters, archives of women’s organizations, transcripts of women’s radio shows, and programs from women’s colleges, Linda M. Grasso shows how and why feminism and O’Keeffe are inextricably connected in popular culture and scholarship. The women’s movements that impacted the creation and reception of O’Keeffe’s art, Grasso argues, explain why she is a national icon who is valued for more than her artistic practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Equal under the Sky by Linda M. Grasso in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Artist Monographs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Living Feminism in the 1910s

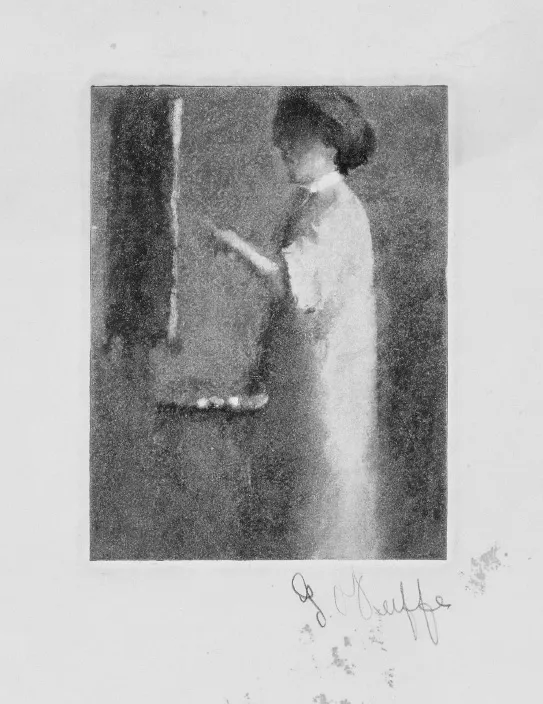

AMONG GEORGIA O’KEEFFE’S apprentice works is a print of a woman painting while wearing professional artist attire. The figure is gendered female by the rounded slope of her shoulder, slender forearm, and abundant hair, which covers her forehead and is bound in a beret. Unconstricted by buttons, belt, and long sleeves, she wears a long white smock and stands close to an easel, applying paint to a canvas. She is luminous against a muted dark gray-brown background, exuding energy and concentration. Her upraised arm, hand, and paintbrush, appearing as a seamless line, are the focal points of the composition; they bifurcate the picture, echoing the vertical line of the easel and the horizontal line of the palette. Positioned below the easel, close to the woman’s body, the palette glitters with color. The vertical and horizontal lines, along with the bright white edging on the easel, a spot of white on the palette, and the woman’s white collar, connect the painter and her tools. We see her from the side, as if we are looking through a window, as she paints. It is a tantalizing perspective because we watch the process of creation without being privy to the results. Our partial view of the close-cropped figure emphasizes our privileged entrée into the painter’s physical and psychic space. Her concealed eyes and averted body telegraph that she is oblivious to distraction. Sight is hers alone. She looks intently at the easel, not at us, and her painting is visible only to her. Alone and deeply absorbed, she is self-contained, energetically engaged in the act of art making. Her working arm, artist tools, and focused intensity mark her as a professional.1 Painting clothes and posture assert that she is a male artist’s equal.

The untitled print of the woman painting, which O’Keeffe most likely made when she attended the Art Students League in 1907–1908 in her early twenties, is eloquent with youthful desire and historical meaning. Whether the print is a self-portrait or a representation of a peer is irrelevant. Most significant is that O’Keeffe visualizes a woman enacting an artistic self. The woman in the print is a painter, not a male artist’s model, muse, or imaginative fodder. Art making, not the artist’s looks, charm, or status, is the focus of attention. By rendering a female painter while she is an art student, O’Keeffe pictures her desire and practices becoming a professional artist.

1.1. This monotype, which O’Keeffe made while she was an art student, expresses her youthful desire to imagine a professional artist who inhabits a female body. Georgia O’Keeffe, Untitled (Woman Painting), ca. 1907–1908. Monotype on paper, 3 ⁷⁄₈ × 3 (9.8 × 7.6). Private collection.

This print is proof of O’Keeffe’s ambition and capacious skills in multiple mediums. Printmaking was not regularly taught at the Art Students League until a comprehensive program was established in the early 1920s. O’Keeffe may have learned to do monotypes in a class, from peers, or through self-guided experimentation.2 Her pride in mastering monotype technique is evidenced by her decision to claim and preserve this early work. She signed it “G. O’Keeffe” in large script and kept it for years after she made it. Using a signature that consisted of an initial rather than her full first name downplayed her gender identity and stressed her genderless professionalism.3 If O’Keeffe ever made other images of a woman painting, they do not survive. After she achieved fame, she did not allow others to photograph her while she was painting.4 As in the print, she insisted that the act remain private, hidden, and mysterious. In order to claim this prerogative and continually refashion her artistic sensibility and public persona, she first needed to imagine a professional artist who inhabits a female body painting a canvas on an easel.

“Simply by its existence, example is enabling,” Roxana Robinson, one of O’Keeffe’s biographers, concludes. “The fact of it permits other people to behave in a similar manner. Georgia O’Keeffe, by her example, gave permission to following generations of women to give work priority in their lives, to consider it crucial.”5 Robinson articulates a sentiment that countless female admirers express in fan letters, testimonials, and honorary award statements. However, in order for O’Keeffe to become an enabling example, she needed enabling examples of her own. Feminist philosophies, practices, and movements created the conditions that made O’Keeffe’s enabling examples possible.

“I got Floyd Dell’s ‘Women as World Builders’ a few days ago and got quite excited over it,” O’Keeffe wrote to her friend Anita Pollitzer in 1915. “The professor was very much interested in Feminism—that was why I read it—” “The professor” with whom O’Keeffe was romantically involved at the time was “very much interested in Feminism” because the newly named movement was an integral part of modernist culture. That a man prompted O’Keeffe to read a male-authored book about feminism demonstrates that in this period feminism traversed gender boundaries. “Certainly never before, and probably not since,” writes historian Christine Stansell of the men and women who sought to create a new modern society through the fusion of radical art and politics, “did a group of self-proclaimed innovators tie their ambitions so tightly to women, and not just a token handful but whole troops of women, waving the flag of sexual equality.”6

In the 1910s, feminism as idea and lived practice was fresh, new, and invested with transformative power. “Writers, artists, and critics saw in feminism not only a liberal idea about equal rights for women,” historian Elizabeth Francis explains, “but also a force of liberation in avant-garde art, cultural radicalism, and revolutionary politics.” Feminism provided O’Keeffe with an imaginative community and legitimated her ambition. It also seeded the possibility that she could “make the world go crazy” through drawings and paintings by conveying “things I feel and want to say,” just like male artists.7

O’Keeffe “got quite excited over” Floyd Dell’s book because it presented lively portraits of powerful women who fed her imagination. Although she tells Pollitzer she read the book because Arthur Macmahon, the “professor” with whom she was in love, “was very much interested in Feminism,” it was neither he nor Dell who introduced her to feminist values and philosophies. She was already living them as a prototypical “New Woman.” By 1915, she had left her familial home, attended educational institutions in Chicago and New York City, and become an independent wage earner. At twenty-eight, she was educated, unmarried, mobile, and ambitious, a perfect reader for Women as World Builders: Studies in Modern Feminism.

The feminism Dell describes in Women as World Builders appealed to O’Keeffe. The book is premised on the idea that feminism is embodied, practiced, and personalized in individual women. The ten women Dell features, he explains, are indicative of the “individual flavor, the personal tone and color” of the feminist movement. The implication is that feminism is a collectivity that nourishes individuality. In his discussion of each “world builder,” Dell puts a premium on women’s ambition, meaningful work, and equality with men. Within the next three years, O’Keeffe would read work by two of the women, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Olive Schreiner, hear about one of them, Emma Goldman, mentioned in a letter from Alfred Stieglitz, and give a talk about another, Isadora Duncan, whom she had seen perform.8

In Women as World Builders, Dell contends that feminism is meaningful and change making in both private and public life. Because men are attracted to women who are “self-sufficient, able, broadly imaginative and healthy-minded,” feminism facilitates equitable romantic partnerships. These relationships can flourish in a new kind of daily living, which Charlotte Perkins Gilman helps men and women imagine. Gilman denounces material conditions that make women’s lives petty and insignificant. Women’s energy, she argues, should not be squandered on useless, repetitive domestic tasks.9

In both public and private domains, Dell maintains, feminism is about expansion, enlargement, and acquisition: “If the woman’s movement means anything, it means that women are demanding everything. They will not exchange one place for another, nor give up one right to pay for another, but they will achieve all rights to which their bodies and brains give them an implicit title. They will have a larger political life, a larger motherhood, a larger social service, a larger love, and they will reconstruct or destroy institutions to that end as it becomes necessary.” Isadora Duncan’s feminist contribution is especially significant, Dell claims, because she exhibits “a new freedom of the body and the soul.” “It is to the body,” he opines, “that one looks for the Magna Charta [sic] of feminism.” Quoting from Duncan at length, Dell rhapsodizes along with her: “The free spirit,” according to Duncan, “will inhabit the body of new women.”10

In Dell’s vision, feminism is ultimately about development, cultivation, and courage. It is multiple and generative. There is not one way to practice feminism, he concludes. On the contrary, each of the subjects he chooses demonstrates that there are many approaches. “Woman as reconstructor of domestic economies, woman as a destructive political agent of enormous potency, woman as worker, woman as dancer, woman as statistician, woman as organizer of the forces of labor—in these it has been the intent to show the real woman of today and of tomorrow.”11 Women can live and practice feminism through various forms of art, politics, theories, and activism.

As Dell’s interpretation suggests, in the 1910s as well as today, three tenets undergird feminism regardless of how people perceive it and enact it in their daily lives: One principle is that gender hierarchy is created by human beings and is not biologically innate or ordained by a deity. A second is that gender inequity is a form of injustice. And a third is that action is needed on behalf of women as a collective group to alter existing bias and discrimination.12 Also like today, in the 1910s feminism advocated justice for women, but race and class injustices affected if and how women saw each other as “women,” experienced oppressions, and determined their activism. For women of color, racial injustice compounded gender injustice. “It should not be necessary to struggle forever against popular prejudice, and with us as colored women, this struggle becomes two-fold, first, because we are women and second, because we are colored women,” Mrs. Mary B. Talbert declared in a “Votes for Women Symposium” published in the Crisis, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) monthly magazine. The women’s movement and feminist communities, organizations, and publications were, for the most part, racially segregated. Some theorists used racist, imperialist, and anti-Semitic thinking to argue that women’s “progress” was crucial to the development of modern civilization and white racial purity. Living feminism in a culture structured by white racial dominance and class hierarchy compelled individuals and groups to invent a multitude of logics, emphases, and practices, not all of which were named “feminist.” What holds true for all, however, is that feminist ideologies authorized women, along with men, to imagine freedom in modern society—whether freedom from indignity, disenfranchisement, poverty, violence, and dependency, or freedom to desire “everything in the world.”13

The teachers, mentors, friends, and lovers who nurtured O’Keeffe’s nascent artistic desire demonstrated in their attitudes and actions that they were affected by feminism as it was broadly conceived in the early twentieth century. All these people believed a woman, like a man, could be a serious professional artist, and they communicated this confidence in their attentive responses to O’Keeffe’s talents. This was also true of the women’s clubs, colleges, critics, reporters, and patrons who kept O’Keeffe’s art publicly visible and confirmed its value from the 1920s to the 1960s. Such support was especially critical when feminism, like other radical movements, was vilified in the late 1910s, then in following decades associated with bourgeois indulgence by the left and denounced as deviance in popular culture and social reform efforts. When feminism again thrived in another era of radical activism in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, the students, teachers, artists, and scholars involved in women’s rights and liberation movements brought renewed interest to O’Keeffe and solidified her place in American art history.

Feminism flourished twice during O’Keeffe’s lifetime: first in the 1910s when she was unknown and in her twenties and then again in the 1970s when she secured iconic status and was in her eighties. As word and concept, feminism was invented when O’Keeffe was a child and became commonplace in the United States when she was forging a professional career in art, working as a freelance commercial artist and as an art teacher, and partnering with Alfred Stieglitz. Originally coined by a French women’s rights advocate, Hubertine Auclert, in the 1880s, the word became part of European vocabulary in the 1890s. Translated into English from the French feminisme, the term gained currency in the United States in the 1910s.14 Members of Heterodoxy, a “club for unorthodox women” that was formed in Greenwich Village in 1912, were among the first in the United States to use the word and attempt to define it.15

O’Keeffe fits the criteria of an “evolved feminist” as Marie Jenney Howe, the founder of Heterodoxy, conceived of such an entity in 1914. Participating in “A Feminist Symposium” in the pages of a short-lived socialist journal, the New Review, Howe first notes that the term “feminism” “has been foisted upon us” because the culture needs “an appropriate word” to “register” “that women are changing.” She then proposes that feminism encompasses an amalgam of efforts in “women’s struggle for freedom.” Feminism, she contends, is grand and revolutionary: It is not “one movement” or “one organization,” nor is it “limited to any one cause or reform. It strives for equal rights, equal laws, equal opportunity, equal wages, equal standards, and a whole new world of human equality.” Her repeated use of the adjective “equal” in five different domains underscores the inequities that urgently needed to be eradicated. Employing the rhetoric of equality, Howe aligns feminism with enlightenment and natural rights ideologies that ennoble rationality and democratic principles.

In Howe’s conception, rectifying inequity is just one dimension of how feminism impels a “changed world.” The other critical component she discusses reveals how early twentieth-century feminist theories are imprinted with modernist vocabulary and concepts. Utilizing the newly popular language of psychology, Howe co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Georgia O’Keeffe and Feminism

- Chapter One: Living Feminism in the 1910s

- Chapter Two: The Artist Idea

- Chapter Three: Women in the Picture

- Chapter Four: “You Are No Stranger to Me”: Women’s Fan Letters

- Chapter Five: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Self-Portrait

- Chapter Six: Feminism as Politics and Art

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index